Access to high-quality family planning services is essential to an individual’s ability to manage their sexual and reproductive health (SRH), manage pregnancies as desired, and prevent and treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The Title X Family Planning Program (Title X) is the only federal grant program dedicated to providing free or low-cost comprehensive family planning services at clinics across the United States. As such, Title X plays a key role in promoting access to pregnancy prevention methods and education and ensuring individuals’ family planning needs are met.

Although Title X mitigates some of the financial barriers to accessing family planning services, individuals nevertheless face persistent logistical or structural barriers to receiving care, including staffing shortages, the need to take time off work, lack of transportation, and lack of child care. Many individuals also experience social barriers to comfortably accessing clinics and receiving desired services, including community-level stigma around family planning, lacking SRH knowledge, and having concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Moreover, structural racism, both historical and contemporary, continues to create barriers to accessing care. The presence of these barriers to accessing and using family planning services have been well documented in previous literature, as have provider strategies for addressing logistical barriers. However, much less is known about how providers respond to and seek to mitigate social barriers, particularly in the Title X context.

Child Trends conducted interviews with staff from more than 40 Title X clinics to better understand how providers perceive and respond to clients’ social barriers to access. This brief highlights the strategies clinics have implemented to address those barriers and, where possible, staff members’ assessments of the efficacy of their strategies. We hope that documenting strategies implemented at Title X clinics across the United States can serve as resource for family planning staff and promote clients’ access to desired services.

Download

Key findings

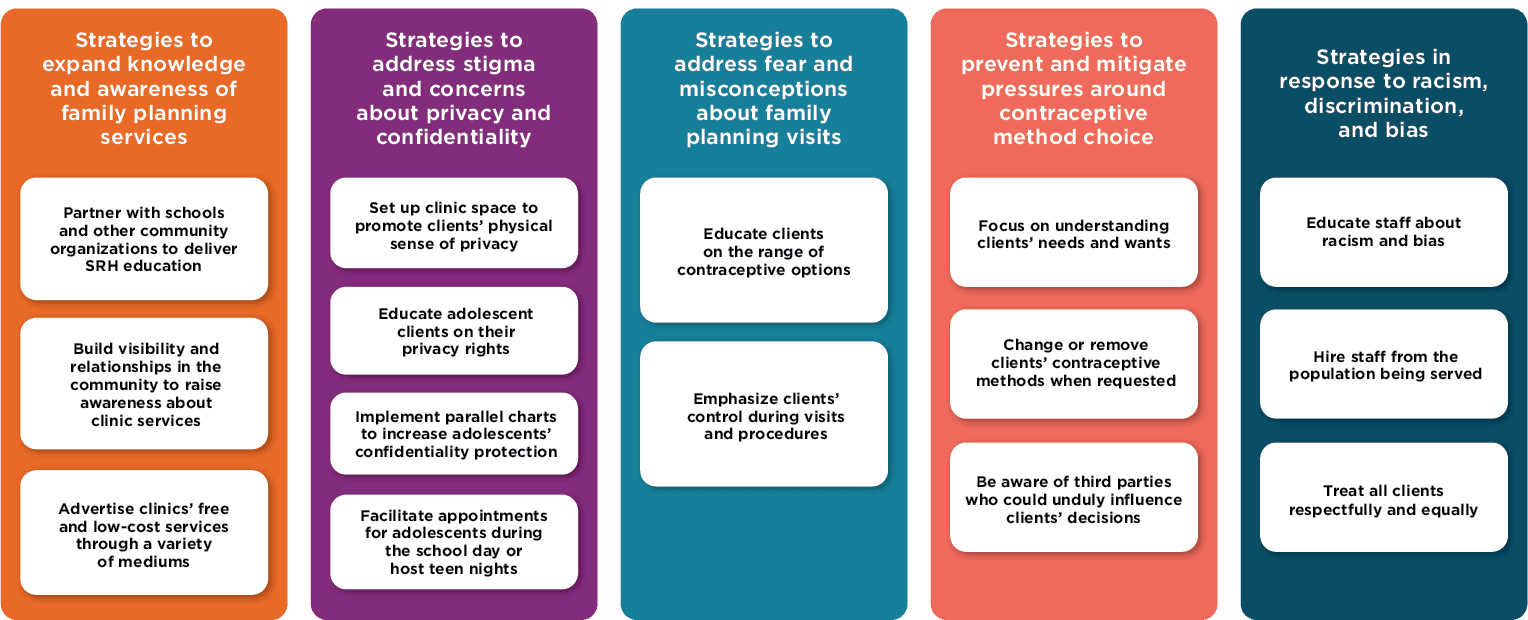

Family planning clinic staff described a range of strategies they use to address clients’ barriers to accessing services:

- Clinics partner with schools and community organizations to deliver SRH education, build visibility and relationships in the community to raise awareness of the clinic, and advertise free or low-cost services through various mediums. These strategies seek to expand limited knowledge and awareness of family planning care in clinics’ communities.

- To address clients’ privacy and confidentiality needs, clinics design their physical spaces to promote client privacy, provide education on privacy rights, create parallel charts, and set up appointments during the school day.

- Clinic strategies to address fears and misconceptions include sharing accurate information about the range of contraceptive options and practicing patient-centered approaches that increase clients’ sense of control during appointments.

- To prevent and mitigate pressures around contraceptive method choice, clinic staff take patient-centered approaches to understanding clients’ needs and wants, change or remove clients’ contraceptive methods when requested, and are aware of other parties who could unduly influence clients’ decisions about contraceptive methods.

- Some clinics have implemented strategies to address racism, discrimination, and bias, including holding racial equity trainings and hiring staff from the population being served.

Methodology and Data

This brief is part of a larger research study on trends in publicly funded family planning services. From February 2020 to January 2021, we conducted hour-long, semi-structured interviews with staff at 46 current and former Title X clinics across the country. Staff included family planning coordinators, clinic managers, registered nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians. During these interviews, we asked staff what they perceived to be barriers to clients accessing family planning services at their clinic and about the strategies clinics implemented to increase access to services. Interviews were transcribed and then coded in Dedoose using a blended approach combining codes developed both from the interview protocol and in response to the data. To ensure inter-rater reliability, we double coded multiple interviews and then reconciled differences through a consensus-building process. Barriers to access, and strategies used by clinics to address them, were coded using the following categories: attitudes toward family planning, clinic hours, knowledge, racism, staffing, and transportation. We thematically analyzed coded excerpts to understand the patterns, prevalence, and tractability of barriers, and the presence and efficacy of related strategies. Through this process, we homed in on strategies used to address barriers in the categories of “attitudes towards family planning,” “knowledge,” and “racism,” and identified the five themes described in this brief. After drafting the brief, we engaged in a member-checking process in which we shared the product with all interview participants and invited their feedback. Eight clinic staff members responded with comments, all of which suggested that our interpretations of the data aligned with their experiences.

Presentation of Findings

Despite the financial barriers to family planning care that Title X helps mitigate, clinic staff in this study nonetheless described encountering significant barriers to ensuring that individuals in their communities could comfortably access clinics and receive desired services. Staff perceived a wide range of barriers, from lack of transportation or child care, to fears about contraceptive methods, and worries about privacy. Both logistical (e.g., transportation, clinic hours) and social (privacy concerns, fears about contraceptive methods) barriers to access, as well as strategies for addressing logistical barriers, have been well documented in previous literature. However, there is a lack of information regarding how clinic staff address patients’ social barriers to access. Our analyses identified five groups of strategies that staff use to address different types of client barriers: building partnerships and visibility to expand knowledge and awareness of family planning; redesigning clinic spaces and educating clients on privacy rights to address concerns about confidentiality; emphasizing client options and autonomy to address fear and misperceptions about family planning visits; taking a patient-centered approach to prevent and mitigate pressures around contraceptive method choice; and hiring strategies and staff training in response to racism, discrimination, and bias.

Provider strategies to address barriers to accessing family planning

Building partnerships and visibility to expand knowledge and awareness of family planning

Background

Most family planning staff we interviewed identified clients’ limited knowledge of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and limited awareness of family planning care, especially the availability of free or low-cost care, as factors that prevent or delay accessing services.

Despite many clinics being well-established in their communities, some staff identified that clients’ lack of “knowing where to go” was a barrier to seeking services. Staff also discussed clients’ concerns about the cost of care, as some do not know that clinics provide affordable services for low-income and uninsured individuals through the Title X program.

Among clients that do access services, some do so less frequently than recommended. Clinic staff explained that some clients are unaware of the importance of routine, preventive care, like annual gynecological exams. Additionally, concerns about cost lead some clients to delay getting their preferred contraceptive method. Clinic staff also highlighted the role that limited knowledge of SRH plays in service utilization. This barrier is especially pronounced among adolescents.

Among the clinics in our sample, efforts to increase knowledge of SRH tend to target youth while efforts to increase awareness of the clinic and available services target a variety of demographic groups or the community at large. Many clinics leverage partnerships with other community organizations to help reach individuals they struggle to reach on their own.

Strategy: Partner with schools and other community organizations to deliver SRH education.

To increase knowledge among youth outside of clinics, many staff emphasized the importance of partnerships with schools, juvenile detention centers, and other community organizations. Through these partnerships, clinics can present on SRH topics, host question and answer (Q&A) sessions, or deliver more in-depth educational programming. One interviewee explained, “We go into the schools, and we can put out the contraceptives on the table and let them look and hold and feel and talk about it. And we start that usually around the freshman year.”

A clinic staff member or outreach worker typically delivers educational programming along with information about the clinic, its services, and how to access them:

“We work closely with them to provide, as comprehensive as the school district will allow, information about birth control and sexual health, relationship safety, STI prevention—all that good stuff. So that’s a major way that we are providing outreach education to the community and also hopefully getting some of those students with initial understanding and comfort with what we do [at the clinic], so that they could be able to come access services.”

One interviewee expressed confidence that school-based outreach is an effective strategy. They explained how there is always a bump in the number of adolescents who visit the clinic “after [they’ve] gone out to 10th grade sex ed and just done [their] spiel.” An added benefit of these interactions is that students get to meet a staff member from the clinic. One interviewee noted that the same outreach worker who provides programming in schools also conducts intake at the clinic, so if students choose to access services, they are greeted by “a familiar face.” During school or community programming, clinic staff can also address other factors that may prevent adolescents from accessing services (e.g., transportation barriers) through tailored strategies (e.g., leaving bus passes for youth).

Community and school characteristics serve to facilitate, or hinder, clinics’ efforts to increase knowledge among adolescents. One interviewee explained that it often comes down to the willingness of school administrators, “Sometimes we can get in and get ahold of some of the really good principals or something in the schools and they’re like, ‘Oh, yes, please. Educate my kids.’ […] So, it just depends on the school.” When clinics are not able to directly engage in knowledge building in schools, they can still leverage relationships with individual school staff, such as school nurses, to share information with students.

Strategy: Build visibility and relationships in the community to raise awareness about clinic services.

Partnerships with community organizations are also valuable for reaching adults—in particular, underserved groups of adults. Clinic staff discussed partnerships with residential treatment facilities, homeless shelters, soup kitchens, and domestic violence shelters that help them share information about the clinic and connect people with services. Some clinics try to reach a wide variety of community members “where they are” by visiting frequented places such as laundromats, gas stations, hair salons, food banks, and probation offices.

Many staff also emphasized the value of maintaining a visible presence in the community, such as by attending health fairs, festivals, or other events. Being active at community events creates opportunities to conduct health screenings, provide education, distribute condoms, and schedule appointments. It can also help build relationships with community members, “so people feel like they can come to your clinic and it’s a safe and trusted place.” While some clinics focus their outreach on the community at large, others target specific groups. One interviewee reflected on their clinic’s outreach efforts within the LBGTQ community:

“I would say that we have an amazing health promotions team and they are integrated into the [LGBTQ] community. I mean they’re on college campuses. They go out into community events. They have different drag events. They’re always doing [STI] testing.”

Many clinics have dedicated community health workers or outreach workers to raise awareness about family planning services and connecting people with those services. Staff at clinics that have community health workers view them as invaluable, whereas those at clinics that do not have staff dedicated to outreach activities viewed this as a barrier to raising awareness and improving access. One interviewee said, “Because we don’t have a lot of dollars to spend on outreach, I think our limitations are just how much outreach that we can do to get folks into the community.”

Strategy: Advertise clinics’ free and low-cost services through a variety of mediums.

Most clinics use a combination of traditional advertising (e.g., posters, brochures, and flyers; newspaper and radio advertisements; billboards) and website and social media outreach (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, email newsletters) to raise awareness about their family planning services. Some staff emphasized the need to include critical information in advertisements, such as that services are available at no cost or on a sliding scale. Others emphasized the importance of getting people’s attention through advertising, for instance by attaching condoms to flyers:

“I had more phone calls after that because I feel like it caught their attention to get not only a flyer but a flyer with an actual condom on it. […] You know how it is. You get a flyer. You throw it away. But I think this really got their attention, like, ‘Oh, this is what they do.’”

Several staff expressed uncertainty about the value of social media for client outreach. One interviewee stated, “I can tell you that most of our patients come to us by word of mouth. I don’t know of anybody who says, ‘Oh, I saw you on Facebook.’” Though another noted that having a presence on various social media platforms is still worthwhile, explaining “I don’t know if we’ve really seen an increase of patients coming in to access services. I think it’s been successful as far as people trying to quickly look up where we’re located or what services we offer.”

Redesigning clinic spaces, educating clients about their privacy rights, and other strategies to address concerns about confidentiality

Background

Clinic staff described how community-level stigma and associated negative attitudes about family planning can dissuade individuals from seeking family planning services and may create significant concerns about privacy and confidentiality among clients who do access care.

Many clinic staff noted that members of their community hold negative views of abortion and many incorrectly believe that all family planning clinics provide abortion care, leading to negative views about family planning clinics. One interviewee noted that stigma about abortion, concerns about anti-abortion protestors, and the assumption that family planning clinics provide abortion care, “scares people about access.”

Clinic staff also described client concerns about how people seeking family planning services will be perceived by their community:

“I think that the stigma piece is present in a lot of people’s maybe discomfort with accessing reproductive services. […] I’ve had a lot of people tell me like, ‘Oh, well, I don’t need family planning services because I’m married.’ I think there’s a stigma that like, ‘Oh, those people who need those services, and I’m not one of them.’”

This sense of stigma and discomfort was particularly prevalent in smaller communities with less anonymity. In one small and religious community, the interviewee reported that even picking up prescription contraception from the pharmacy after visiting the clinic creates discomfort and privacy concerns because the pharmacist is a local religious leader.

Clinic staff also highlighted how adolescents are often particularly concerned about privacy and confidentiality because they worry about their parents’ potential negative reactions. Staff described adolescents’ worrying about family members seeing them at the clinic or that medical records could be shared with family members.

Strategy: Increase clients’ physical privacy.

To increase clients’ physical privacy, one clinic redesigned their space so that family planning is integrated with the other specialties, which can shield the purpose of a client’s visit. Several staff also noted that, although it is not a deliberate strategy, the fact that their clinics operated under more general names like “community health center” or “health department” could serve to protect the privacy of family planning clients. One interviewee explained: “I think being part of a health center and CHC [community health center] is helpful because people come in, not just to a family planning clinic, so people don’t think they’re just accessing family planning services.” Some clinics also noted that they dispensed contraception directly to clients who were concerned about their privacy at the local pharmacy.

At clinics where family planning was not integrated with other services and/or located in small town communities, staff suggested clients park in alternative locations or highlighted that clients could travel to sister clinics in neighboring counties if visiting the clinic in their small town was too concerning.

Strategy: Address adolescents’ unique needs and concerns.

Educate adolescent clients on their privacy rights.

Many clinic staff reported that educating adolescents and parents on adolescents’ legal rights to privacy and confidentiality was an important age-specific approach to promoting adolescents’ access to family planning services.[a] Staff inform adolescents of their rights under Title X during outreach in schools and other settings because understanding their privacy rights can be an important first step to adolescents feeling comfortable seeking services: “We do have confidential services and tell [adolescents] that so that they’re not fearful of [their information being shared with their parents], and that that would stop them.” Staff also noted that providers asking parents to leave the exam room at certain points allows adolescents to access the family planning information and services they need: “And so often times it happens there where […] parents step out and then our provider opens up that conversation [about family planning], and then the young person’s like, ‘Oh, yeah. I want to talk about all of this.’”

Implement parallel charts to increase adolescents’ confidentiality protection.

Many clinic staff discussed strategies related to their electronic medical records (EMR) systems to address the specific confidentiality needs of adolescents. Normally, parents or guardians have access to their minor children’s medical records, but to protect the confidentiality of adolescent client’s Title X services, like birth control or STI testing, clinics can create parallel patient charts that are not shared with parents or guardians. Services provided under these parallel charts are not billed to parents’ insurance, and visits booked under parallel charts often do not receive reminder phone calls. Staff expressed confidence in this strategy, with some highlighting that these features can also benefit clients of any age who need additional confidentiality around their family planning care.

Facilitate appointments for adolescents during the school day or host teen nights.

For adolescents who want to access family planning services without their parents finding out, having an appointment during the school day can help protect their privacy. Several clinics adjusted the clinic schedule to accommodate adolescents during their lunch hour. One clinic worked with the school district to arrange for students to check out for day-time clinic visits with the school counselor instead of going to the front office to check out. This way, students’ whereabouts were accounted for but there was no risk of the front office notifying parents, which is standard practice when students leave during school hours. Other clinics offer dedicated “teen nights” or “teen clinic hours” when adolescents could come to the clinic with no risk of running into known adults. However, a few interviewees noted these dedicated sessions for adolescents were not well attended and that focusing on making appointments available at times that were accessible to adolescents was a more effective strategy.

Emphasizing client options and autonomy to address fear and misconceptions about family planning visits

Background

Several clinic staff described clients’ fears related to birth control, gynecological exams, and specifically insertions of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) as barriers to clients accessing the methods and care that would otherwise fit their needs. Staff expressed that some of these fears stem from inaccurate information about family planning that is prevalent in clients’ communities. One interviewee explained, “I think that the topic of family planning in a lot of cultures has been taboo, and I think that’s limited [clients’] … knowledge or their comfort of coming in if they’ve never had a pelvic exam or a gynecological exam. I think the fear of the unknown is a real barrier.”

In particular, staff expressed that clients have significant fears of LARCs. LARC insertions can be invasive and painful, and clients can feel uneasy about a method that is inserted into their bodies. Further, several providers noted a high prevalence of inaccurate information about LARCs in their community. One interviewee described some of the concerns:

“Every person that I tried to talk about a LARC as an option for them [would say] ‘So, I really heard that the partners can feel the strings and that there’s so much bad cramps, and my girlfriend got 30 pounds on that.’ […] I think so much of the decisions around reproductive health are driven by what we’ve heard from people we’re close to […] [and by] cultural norms and the myths in the community about what certain side effects are from the choices.”

Inaccurate information is not limited to LARCs, but also exists about birth control more broadly. One interviewee lamented that “There are so many old wives’ tales about birth control” and another shared that “There’s still a lot of fear that birth control will make you sterile.”

To address barriers related to fear and misperceptions, clinic staff’s primary strategies were educating clients with accurate information about family planning and contraception, and implementing more patient-centered approaches to care during appointments.

Strategy: Educate clients on the range of contraceptive options.

To address commonly held beliefs about contraception and promote transparent and accurate information, staff help clients understand more about family planning and the range of options available to them. One clinic dedicated reproductive care coordinators to focus on client education in the clinic setting. In this clinic, having these coordinators has been “really helpful” because they “have that line to engage patients and provide both counselling and education and then discuss the side effects and then help to manage them.” Other staff described education efforts as challenging because clients had strong beliefs and opinions about different contraceptive methods. In particular, one interviewee explained, “We just also educate them about all of the different methods that a lot of times they’ll just shake us off and say, ‘No, I don’t want to hear about all those.’”

Strategy: Emphasize clients’ control during visits and procedures.

To address clients’ fear and discomfort during more invasive procedures, one staff member emphasized the importance of increasing clients’ sense of control. The staff member described giving the client options to move through the exam at a slower pace, or even reschedule the appointment if the client becomes too uncomfortable. Here the interviewee describes this focus on clients’ comfort and autonomy:

“The other thing is, sometimes when they come in, if they want birth control, I’ll say, ‘If you’re not ready to have an exam right now you don’t have to. We can schedule it down the road.’ Or if when I am maybe putting in speculum in the first time in a lady. If I can see that she’s grimacing or that she’s so uncomfortable, I stop and I say, ‘You know what? We don’t have to continue this. We can reschedule.’ So giving them options I think is important, and I try to do that.”

Taking a patient-centered approach to prevent and mitigate pressures around contraceptive method choice

Background

Some clinic staff described clients facing pressure from partners, family members, or other family planning providers when considering different contraceptive methods, thereby infringing on clients’ autonomy and ability to access their preferred contraceptive method.

Staff noted that some romantic partners exert influence on clients’ contraceptive method choices. One interviewee described how if a client says “‘I need to talk to my partner about [contraceptive method],’ [I] may not see them again.” While other factors may influence clients’ decisions about contraceptive methods, this provider expressed concern about the possibility of reproductive coercion impeding their ability to move forward with their preferred method. Other clients explicitly tell providers that they want a contraceptive method that their partner will not be aware of. One interviewee shared that many clients have said, “‘My partner doesn’t want me to be on birth control, but I want to get on something that they don’t know that I’m going to have.’” Clients’ partners may also influence their decisions or abilities to access family planning services at all, which in turn affects the contraceptive method choices and information clients have access to. Another interviewee said, “Sometimes, I’ve even had a wife come in and need services and not want their husband to know.” Although the clients sharing these needs with staff were able to access services, their experiences point to other individuals in situations of reproductive coercion who are likely unable to.

In addition to romantic partners, family members, especially of adolescents, can also interfere with client autonomy in relation to family planning care. One interviewee discussed meeting with adolescent clients who are “automatically hesitant because they know that their family members don’t want them to be on [a contraceptive method].”

Some staff also acknowledged the history of contraceptive coercion in the family planning field and ongoing attempts from providers to influence clients’ contraceptive choices. For example, one interviewee described how she previously worked at clinics where providers engaged in coercive practices by “push[ing] LARCs on patients” or convincing patients to not remove their IUD or Nexplanon. Another interviewee discussed how some providers’ attitudes are that, “[LARCs are] the best for [the teen] population because teens shouldn’t be pregnant and everybody should get a LARC, and then if they wanted out, you should try to troubleshoot it.” While interviewees did not describe coercive behaviors at their current clinics, they recognized providers may pressure their clients about their contraceptive method choice.

To ensure that clients can access their method of choice, staff emphasized taking a patient-centered approach to understanding clients’ goals and preferences, respecting clients’ wishes about changing or removing contraceptive methods, and being attuned to the potential for other parties to exert influence on clients’ decisions.

Strategy: Focus on understanding clients’ needs and wants.

The most common strategy that clinic staff used to guard against contraceptive coercion and pressure was focusing on the clients’ needs and wants and emphasizing bodily autonomy during clinic visits. During contraceptive counseling appointments, staff intentionally asked questions related to clients’ lifestyles and contraceptive method preferences:

“We’re really looking at asking the client what fits the best, and their lifestyle best, and what they think would be better […]. So, we try and really be open to what they’re interested in, and then just briefly tell them that there may be other methods out there and give them information, so they know.”

For clients with romantic partners, staff explained that asking questions about clients’ relationships helped providers assess safety concerns like potential intimate partner violence or reproductive coercion. One interviewee reported asking questions, such as “What’s the partner like? Do they use a condom every time or not? […] Whether or not they have [intimate partner] violence, if there’s something going on.” In situations where providers learn that clients need to ensure their partner will not discover their contraceptive method, one strategy was placing an IUD and “cutting IUD strings very short.”

Strategy: Change or remove clients’ contraceptive methods when requested.

Communicating to clients that they can have LARC methods removed at any time, and conducting those removals when requested, was also noted as an important strategy to reduce contraceptive method pressure and influence from providers. One interviewee said that maintaining a patient-centered focus regarding the removal of LARCs promotes trust building with clients: “I think that really helps, especially over time, build rapport with patients and results in more honesty, which results in better care.”

Strategy: Be aware of other parties who could unduly influence clients’ decisions.

Additional strategies clinic staff discussed to protect clients’ contraceptive method decisions from undue pressures included being deliberate about who is present in the exam room with the client and emphasizing to the client that their decision is confidential. For example, clients may bring a partner, friend, or family member to their visit, but one interviewee shared that they purposefully bring clients into the patient room alone first to prevent possibly coercive situations and protect confidentiality. Relatedly, another interviewee emphasized the importance of increasing clients’ awareness of confidential clinic services, saying, “Sometimes it’s actually the education piece of it and knowing that they can come in here and that it’s confidential and that they don’t have to worry.”

Related Content

- Promising Practices for Expanding Students’ Awareness and Use of School-based Family Planning Services

- Family Planning Practitioner Perspectives on Developing Partnerships to Provide Services in Schools

- How Family Planning Providers Are Addressing Clients’ Reproductive Health Needs During COVID-19

- Trends in Family Planning Service Provision

Hiring strategies and staff training in response to racism, discrimination, and bias

Background

Given the well documented racial disparities in SRH care and outcomes, the research team asked interviewees explicitly about racism, discrimination, or mistrust as barriers to accessing care. Clinic staff varied considerably in their perception of racism, generally, and its role as a barrier to care. Many interviewees expressed that they did not perceive racism, mistrust, or bias as barriers to clients with marginalized identities accessing services at the clinic. These staff tended to work at clinics that served lower proportions of Black or Latinx clients and were more likely to be located in rural areas. Some of these staff cited the ability of clients of color to access services at the clinics as demonstrating the absence of barriers for this population, saying for example, “I can only think of two [clients] that are either African-American or Hispanic who come to see us, and they don’t have any problems getting care. So, I don’t see it as a barrier.”

Other clinic staff described an awareness of racism in medical settings, generally, but believed that it was unlikely to be an issue in their clinics. These interviewees recognized dynamics including the legacy of medical racism, its relationship to racial disparities in health, and how it has created community mistrust of health care systems, but concluded that racism was not an issue at their clinic. However, other staff felt it was inevitable that the dynamics and history of racism and bias were present in their clinics. These staff tended to work at clinics with higher proportions of Black and Latinx clients and were more likely to be located in urban areas. One interviewee explained: “there’s a lot of biases or sometimes fear that patients can feel that they are not receiving the same quality of care or services as someone who was White.” At least one interviewee described how racism is intertwined with pressure or coercion around clients’ contraceptive method choices:

“I talked about LARC […] and there’s coercion with that. [ …] In the past, people have been forcibly sterilized, people have been discriminated against from folks like they’re looked down upon if they have another pregnancy right after a pregnancy and they choose not to have birth control. They are made to feel bad […] I think that people don’t seek services in the clinical healthcare system because they felt worried about the judgment they’ll receive or the sub-optimal care that they’ll get.”

An interviewee from a clinic that served a significant proportion of Black youth also highlighted concerns about their clients’ vulnerability to pressure from providers around contraceptive methods, saying “There is a lot of reproductive injustices within the Black community and the thought of a young person going to a space by themselves in a medical center is uncomfortable.”

Strategy: Educate staff about racism and bias.

Among clinics where interviewees described an awareness of racism in medical settings, some had implemented staff trainings aimed at promoting racial equity and inclusion to address clients’ fears and mistrust rooted in medical racism. One provider explained, “We’re trying our best to recognize now the healthcare disparities that exist in our system, and the institutional racism that exists in our system, and win over the trust of the people that we care for.” Among staff from clinics that had conducted trainings, some felt that this strategy had been successful, saying “I think that the trainings have brought to light things or events, or feelings that some of us might have never even thought would be a problem but are a problem.”

Strategy: Hire staff from the population being served.

Providers, particularly those who served more diverse client populations, also discussed deliberately hiring staff who share the racial or cultural identities of their clients to promote comfort and trust among clients of color. One interviewee highlighted the importance of having “good representation at multiple levels of staff, and staff who are members of the community that we’re trying to reach.” Another interviewee described their clinic trying “very hard to try to find employees that … know about our patients and look like our patients so that […] they feel more comfortable coming to us.”

Strategy: Treat all clients respectfully and equally.

Staff from other clinics, some that acknowledged racism as a barrier and others that did not, discussed the importance of not just serving everyone, but treating everyone equally and with respect. For example, one interviewee said “Always on our feedback forms, one of the main things people note or write in this comment is that they felt they were treated with respect. So that’s a big issue.” Another interviewee reflected on the importance of connecting with clients and building rapport to promote client comfort:

“I can’t think of anything other than trying to have a decent relationship. I mean, you can generally tell when you’re interviewing someone if they’re trustful versus mistrustful, but sometimes you get them talking on a subject that they have an interest in and […] it’s kind of like breaking the ice within your interview. […] In my mind I say this to myself because I’m just trying to tell if I have racial biases […]: ‘Would you have offered the same services to this person as you offered to this person?’, and if it’s like, yeah, at the end of it we’re good.”

Discussion of Findings

Although clients’ barriers to accessing family planning care are well documented, the field knows less about the approaches that providers use to mitigate barriers to access, particularly in the Title X context. This brief’s unique contribution to the literature is in describing providers’ strategies to address those barriers that relate to knowledge, stigma, fear, and pressures around contraceptive choices.

In our interviews, staff discussed taking patient-centered approaches to gynecological exams, contraceptive counseling, and LARC removals to reduce client fears, build trust, and prevent clients from feeling pressured in their choice of contraceptive method. However, staff also described wanting to provide information on all methods, and expressed frustration that some clients are not open to learning about the full range of available methods. Some providers seemed to feel tension between offering patient-centered care, which is guided by the client’s needs and goals, and the desire to take a comprehensive or tiered approach to contraceptive counseling. Nevertheless, prior research supports allowing clients’ needs and goals to guide these encounters: Patient-centered contraceptive counseling is generally more equitable and respectful of client autonomy and more likely to result in higher contraceptive method satisfaction and continuation.

We also learned more about the role of stigma in preventing access to family planning care and in creating significant concerns about privacy and confidentiality, particularly for adolescents and/or people in small and conservative communities. Staff discussed both general stigma around SRH and about abortion care more specifically. Abortion is a highly stigmatized and politicized form of health care, despite being relatively common, and clinics that provide abortions often face threats, harassment, and violence. Title X recipients are prohibited from using Title X funds for abortion services, and during the timeframe that these interviews were conducted, clinics were also prohibited from providing abortion care using other funding and discussing abortion care with clients. Nonetheless, staff perceived that the local climate around abortion and family planning services, more generally, influenced potential clients’ concerns. Interviewees did not discuss efforts to shift this stigma in their communities, and instead focused on strategies implemented inside the clinics to protect the privacy and confidentiality of clients.

Clinic staff also had varied perceptions about whether racism or bias act as barriers to clients accessing services at their clinics. The interview protocol asked specifically about issues that affect the experiences of women of color seeking care in the clinic, factors like mistrust or racism that may make people hesitant to seek care, and strategies to improve access for marginalized populations. There was a significant disconnect between interviewees who did not see racism in medical settings as a barrier, most of whom serve more White clients in more rural locations; and those who acknowledged racism in medical settings, who tended to serve more Black and Latinx clients in more urban locations. Relatedly, some interviewees who did not see racism as a barrier to access nonetheless described strategies to address racism, including trainings on racial equity, hiring staff from the populations served at the clinic, and treating all clients equally and with respect. We lack information on the demographic characteristics of interviewees from this study, but it is likely that interviewees’ own racial and ethnic identities influenced their perceptions about racism and bias as barriers, as White Americans are less likely than Black Americans to perceive racial discrimination and inequities. Prior research has established that racial discrimination, bias, and negative stereotyping continue to be relatively common for Black women seeking reproductive health care and that these factors engender significant medical mistrust.

This work is limited by its lack of client perspectives, and interviewing only staff especially limited our ability to discuss racism, bias, and medical mistrust. For example, although multiple staff described treating clients equally and respectfully—in response to questions about strategies for improving access to care for marginalized populations—this is not a recognized or recommended strategy for reducing bias or increasing equity in service delivery. To fully understand the extent to which strategies are successful in promoting access to and comfort with services, we must also include the perspectives of Title X family planning clients, as well as individuals who have been unable to access family planning services. This study team is currently engaged in data collection with existing and potential clients to assess their experiences seeking care, and to identify strategies that facilitate access to services.

Despite this limitation, this brief does describe a variety of strategies that Title X clinics use to address barriers related to knowledge, stigma, client fear, and pressures around contraceptive choice. Various clinics across the country have implemented these approaches, ranging from those that are tailored to provide education on SRH services and privacy rights to adolescents to those that center clients’ wishes and sense of control. Health providers that offer family planning services might incorporate some of these strategies to improve their clients’ access to and comfort with family planning services.

Footnote

[a] Under the Title X statute, adolescents are entitled to 1) receive family planning services without the consent of a parent or guardian and 2) receive family planning services without clinic staff notifying their parent or guardian.

Acknowledgments

Contributions

Suggested Citation

Briggs, S., Logan, D., Solomon, B., Kim, L., & Manlove, J. (2022). Title X provider strategies to increase client access to family planning services. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/6167v6800m

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram