School-based health centers (SBHCs) remove financial and logistical barriers that prevent young people from accessing primary and preventative health care, including family planning and other reproductive health services. SBHCs are located in or near schools, which eliminates the need for students to find transportation to make appointments, and offer services for free or at reduced cost. SBHCs are also often embedded in under-resourced communities and are therefore uniquely positioned to reach young people from groups that have been historically excluded from receiving high-quality health care services, including those who are uninsured or underinsured or come from low-income backgrounds. Furthermore, by improving health and education-related outcomes for students, SBHCs play an important role in advancing health equity.

As just one of the many services SBHCs provide, family planning services are particularly important for adolescents. Evidence suggests that students who attend schools with SBHCs that offer family planning services demonstrate greater contraceptive use and have fewer unintended pregnancies. However, many adolescents do not receive recommended preventative family planning care for a variety of reasons, including an overall lack of awareness about the SBHC. Despite their benefits, many students may not be aware that their school has an SBHC at all, or that it offers a range of services. In one qualitative study examining SBHC utilization, students described a lack of awareness of the SBHC’s location and who its providers were, which served as a key barrier in accessing care. Another study found that, as with their awareness of SBHCs in general, many students were unaware or confused about the full range of services that their SBHC provided, including whether contraceptive services could be obtained.

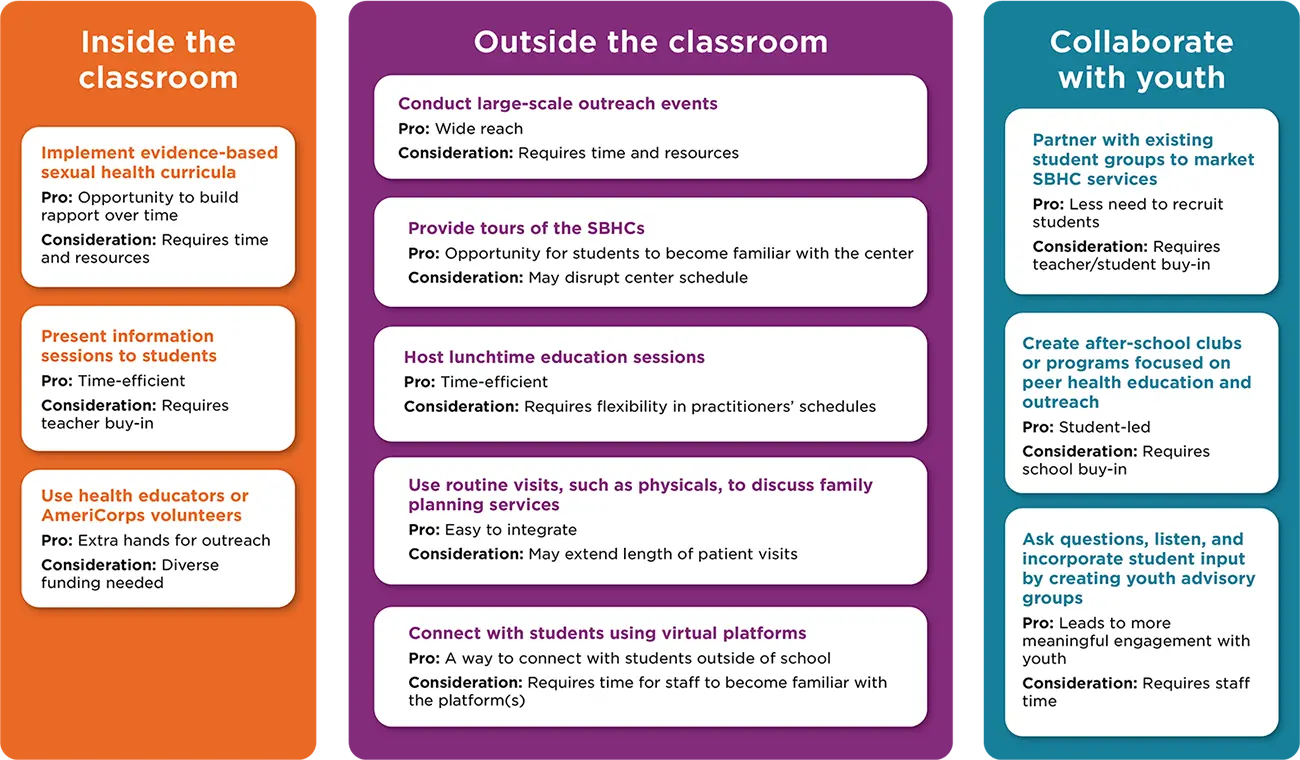

This brief describes strategies that practitioners use to reach youth and increase their awareness and utilization of family planning services offered within SBHCs. We highlight outreach strategies that allow practitioners and other health center staff to (1) connect with youth inside the classroom to present sexual health education and information about SBHC services; (2) create opportunities outside the classroom to provide information about family planning services; and (3) collaborate with youth to brainstorm and implement innovative outreach strategies.

Download

Key Findings

- SBHCs can increase utilization of family planning services by reaching out to students and providing information about the need for and availability of these services at SBHCs.

- Practitioners or health educators can facilitate an evidence-based sexual health curriculum or lead one-time presentations in classrooms to increase students’ awareness of family planning services within SBHCs. Practitioners felt that in-person meetings with students were especially important in creating a sense of trust and familiarity.

- SBHCs can take advantage of time outside the classroom to build students’ knowledge of family planning—and their awareness of other services offered at the SBHC—through lunchtime education sessions, large-scale events or activities, or social media platforms.

- SBHCs can partner with students who are invested in the SBHC and its services to brainstorm and execute innovative outreach strategies.

Outreach Strategies for School-based Family Planning Services

Background and sample for brief

This brief highlights findings and recommendations from interviews with 23 medical providers and administrators from SBHCs, high schools, and community colleges in the United States. Child Trends conducted these interviews from February 2020 to February 2021 as part of the OPA-funded Innovations in Family Planning Clinical Service Delivery for Underserved School-Based Populations project. This project aimed to identify, evaluate, and disseminate successful strategies for providing family planning services to adolescents in school-based settings.

In total, the interviewees for this brief represented 22 organizations in 12 states and the District of Columbia. Of these organizations, 14 operated in urban areas, one operated in a suburban setting, three operated in a rural area, and five operated in a mix of these settings. All organizations reported serving one or more of the following underserved populations: people of color, including members of American Indian Tribes; people with limited English proficiency; people who have immigrated to the United States; people experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness; people with low incomes; and rural communities and communities that do not have accessible family planning clinics.

For more information on the study background, full study sample, and methodology, please see the methodology brief.

Strategies and Promising Practices for Practitioners

Connect with students in classrooms to present sexual health education and information about SBHC services.

The most common approach used by SBHCs to increase awareness and utilization of family planning services was to conduct in-person class presentations. This approach offered SBHCs an opportunity to build rapport with students, provide comprehensive sexual health education, and share more detailed information about the range of family planning services offered. Practitioners used a variety of strategies, including implementation of an evidence-based sexual health curriculum, the presentation of informational sessions to students, and the incorporation of health educators or AmeriCorps volunteers in outreach and health education efforts.

Promising practices

Implement evidence-based sexual health curricula.

Health center staff—including nurse practitioners, public health nurses, social workers, or health educators—implemented evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programming in health classes, ensuring that all participating students received comprehensive family planning education. One SBHC received federal funding through the State Personal Responsibility Education Program to implement the Comprehensive Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention program, in which health educators teach an evidence-based curriculum in health classes. Through multiple sessions, students not only learn concepts related to sexual health, but also develop rapport with health center staff. Of this program, the SBHC manager said, “When you go in a couple of times and they see your face a couple of times, there’s a familiarity about it that I think is very valuable. And by the time we’re done with our eight sessions, they’re like ‘Please don’t go.’”

According to results from a survey that the same SBHC conducts with new patients, most patients learned about the SBHC’s services from the center’s presentations in classrooms. Despite the benefits of implementing evidence-based curricula, some health centers may face challenges with seeking consistent grant funding to pay for facilitators’ time and training, and to incorporate these presentations in health center workflows. Connecting with other schools or organizations that have successfully implemented evidence-based programming can help SBHCs learn about different sustainability approaches.

Present information sessions to students.

Health centers in which implementing a curriculum for an extended period was not possible could provide one-time class presentations as an alternative. One SBHC began to provide “Health Center 101” presentations in 9th and 10th grade health classes after learning from the health teacher that students were unaware of the location of the SBHC and services it provided. The presentations covered information about the SBHC’s staff, its confidentiality policy, the range of services it provided, and comprehensive information about the different types of contraception. Health center staff intentionally conducted these presentations with 9th and 10th graders, recognizing the need to share information early. As a result of these presentations, health center staff saw that more 9th and 10th grade students were visiting the health center and seeking contraception before ever having sex. Another SBHC visited classes at least twice a year to help students familiarize themselves with health center staff and to help teachers feel comfortable referring students who indicated a need for information or services. To present in classes, practitioners noted the importance of identifying and building strong relationships with teachers who are willing to open their classrooms to health center staff. In addition to collaborating with teachers, health center staff should seek support from school administrators and participate in ongoing conversations to underscore the value of providing sexual health education to students.

Use health educators or AmeriCorps volunteers.

Several practitioners mentioned that insufficient time represented a barrier to scheduling and conducting presentations, which led some SBHCs to staff health educators or AmeriCorps volunteers to lead presentations and raise health center visibility. Since health educators and AmeriCorps volunteers are not responsible for clinical work, they have more time available to conduct outreach and education activities outside the health center. At one SBHC, AmeriCorps volunteers collaborated with teachers to teach a comprehensive sex education curriculum and provide information on the state’s minor consent laws and policies around confidentiality. In some instances, health center staff would accompany AmeriCorps volunteers during class presentations and introduce themselves. One SBHC recommended having health center coordinators visit students in the classroom since coordinators are usually the first people that students see when they visit the health center.

A major benefit of having health educators or AmeriCorps volunteers conduct health education and outreach was that they were more easily able to connect with students due to being (typically) younger than practitioners. One practitioner noted that health educators “bring in different kids” and help the health center “reach some of those students that maybe [practitioners] wouldn’t reach.” While there were many benefits to having health educators or AmeriCorps volunteers lead outreach, there were several challenges as well. Staff turnover created difficulties coordinating logistics and building strong relationships with teachers. Health educators were also largely grant-funded and many of their responsibilities were not billable. One health center emphasized the critical need for diverse funding streams for health educators to continue working with students.

Create opportunities outside of the classroom to provide information about family planning services in SBHCs.

Practitioners also identified several creative strategies for improving students’ awareness and utilization of SBHCs outside of classroom settings. These strategies included large-scale outreach events, SBHC tours, lunchtime education sessions, and the creation of educational content for social media platforms. In several instances, SBHCs used one or more of these strategies to supplement in-person classroom presentations. Since these strategies are used outside of class time, practitioners could implement one or more to ensure that class time is not interrupted.

Promising practices

Conduct large-scale outreach events.

Hosting events such as health fairs or sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening events for all students can be an effective way to provide information about SBHCs and their services, and to address specific family planning needs for large numbers of students. For example, AmeriCorps volunteers at one SBHC helped coordinate a schoolwide STI testing day for all students. Students were brought to the gym, where AmeriCorps volunteers and SBHC staff provided information about contraceptives and distributed condoms.

During the event, to protect student privacy, all students were provided with an STI test inside a paper bag to conceal its contents and asked to visit the bathroom. The STI test was completely voluntary; students could decide whether they wanted to take the test once they were in the bathroom. Students then met with an SBHC staff member who provided more information about the SBHC and the services it offered. The practitioner we interviewed shared that conducting a schoolwide STI screening event “[broke] down some of those barriers that people might feel from walking into the clinic” since it demonstrated that the SBHC is not only a place “where the pregnant girls go, or where people go when they have an STD.”

Prior to the event, the AmeriCorps volunteers took “field trips” to STI testing events held by the local health department and Planned Parenthood to learn how to successfully conduct large-scale STI events. The SBHC also partnered with a local lab that processed all STI tests after the event. While these events require a lot of planning and organization, practitioners noted “a good return on investment” because many students made appointments for care—including family planning services—following the events. Note, however, that schools that consider this type of STI screening event must work within SBHC and state parent consent policies.

Provide tours of SBHCs.

Several SBHCs complemented their classroom presentations by offering students a tour of the center. Providing tours allows students to become familiar with the space and ask any additional questions. This strategy may be particularly useful when implemented with students who are new to the school building (e.g., incoming freshmen in high schools), and can make new students aware of the center and its services throughout their time in school. Notably, at least one SBHC transitioned to providing health center tours in lieu of classroom presentations, indicating that this approach had been more successful in leading students to seek care: “Once we started having them come to the clinic, we had way more students coming in earlier. And so instead of coming in after they had sex … they would come after their first day of class and start contraception prior to having sex.”

Host lunchtime education sessions.

Another way to provide information about SBHC services without disrupting class time is to conduct lunchtime education sessions. One SBHC invited all students, by loudspeaker announcement, to attend an education session during their lunch period. To increase attendance, students were offered pizza and small giveaways for attendance (e.g., hand sanitizer). Social workers discussed topics such as sexual health, state-specific confidentiality laws, and healthy relationships. At the end of the sessions, students who were not enrolled in the SBHC were given a consent form for their guardian to sign. SBHC staff also scheduled family planning service appointments for interested students enrolled in the SBHC.

Use routine visits, such as physicals, to discuss family planning services.

In some instances, SBHCs can increase uptake of family planning services by using routine SBHC visits—such as required sports physicals—to open dialogue with students about reproductive health and family planning needs. One SBHC described administering an Adolescent Risk-Taking Screening to students using an iPad or tablet as they waited to be seen for their physicals. SBHC staff briefly reviewed responses prior to meeting with the students; if a student marked “yes” to any item related to sexual activity, the practitioner encouraged them to consider STI testing and family planning services.

Connect with students using virtual platforms.

The use of social media can supplement in-person outreach efforts. Several SBHCs began using social media to tell students how to seek services during the COVID-19 pandemic when many schools and SBHCs were closed. Two SBHCs felt they had been particularly successful at reaching students on platforms such as Instagram and Tik Tok. One SBHC created an Instagram account after their school had an established social media presence, which allowed them to connect their content to the school’s social media accounts and build their following. The other SBHC worked with a youth council, which was responsible for leading social media engagement efforts, particularly on Tik Tok. Notably, some SBHCs did not have as much success connecting with students via social media due to the lack of a social media presence and challenges with creating content that resonated with youth. Schools should consider utilizing established accounts, such as their Instagram page, or involve youth in the development and dissemination of content to maximize reach.

Collaborate with youth to brainstorm and implement innovative outreach strategies for family planning services.

Several SBHCs worked with youth in various ways to increase their presence in schools. Youth—and especially those who are passionate about SBHC services—can promote the SBHC and encourage new clients to seek needed family planning care. Moreover, by incorporating youth perspectives into decisions about health center services and delivery, SBHCs can build a more youth-friendly environment, which in turn increases utilization of services. The strategies below offer some ways that SBHCs can engage youth.

Promising practices

Partner with existing student groups to market SBHC services.

Health center staff leveraged existing student clubs—and particularly those related to health, science, and medicine—to brainstorm and implement marketing strategies and reach more students. One SBHC manager reported that the school administration’s more pressing priorities created challenges in receiving administrative support for the SBHC, and with promoting its services. In particular, the health center had to “walk the line, a very thin line, of not offending administration or parents by promoting contraceptive care.” As a result, the SBHC relied mostly on word-of-mouth as its main approach to promote services to students. To build awareness, the SBHC manager intentionally identified and developed a relationship with the teacher who sponsors the health and science club. The teacher invited health center staff to meet with students in the club and share information about their services, and asked whether the students would be interested in advertising health center services to their peers. The students then brainstormed several strategies, including a short video tour of the health center, social media accounts, and posters to hang around the school. The SBHC manager shared that it is important to “get [youths’] perspective and have them be part of the process because technically, if it’s at their school, it’s their clinic. And if you’re trying to get them in to the clinic, you need it to be youth oriented.”

Create after-school clubs or programs focused on peer health education and outreach.

Several SBHCs created after-school clubs or youth training programs to educate students on family planning topics and promote SBHC services. For example, one SBHC developed a peer advocate program in which 10 selected students participated in ongoing educational sessions to learn about topics related to sexual and mental health. In collaboration with SBHC staff, students planned education and outreach events to share what they learned with others. Events included student education weeks, campaigns focused on specific topics, and presentations about the SBHC and its services at school assemblies. To encourage students to join the program, health center staff provided gift card incentives and emphasized the benefits of including this activity in college applications.

Ask questions, listen, and incorporate student input by creating youth advisory groups.

Some SBHCs also created youth advisory groups whose main goal was to provide ongoing feedback to health staff on ways to better reach and serve youth. One SBHC program asked for volunteers across their health centers and chose two students from each center. The SBHC program held monthly meetings to discuss how students perceive the health center, innovative approaches to reach more students, and how each health center can improve its services to better meet students’ family planning needs. Based on feedback from the youth advisory council, one health center removed STI posters in the waiting room that students felt were “scary” and encouraged all health center staff to receive training on “being an LGBT [and] gender-affirming clinic.” The SBHC manager said that the youth advisory council helps them “reach more of the young people and keep a perspective for adolescents.”

Conclusion

SBHCs provide access to and information on family planning services for adolescents. However, the benefits that SBHCs offer may remain unrealized if students are unaware of all services offered. Investing in outreach efforts can help SBHCs ensure that students are accessing needed family planning services.

As described in this brief, conducting outreach to students encompasses a wide range of activities, such as classroom presentations, health center tours, or STI testing events. SBHCs can use one or more outreach strategies best suited to the needs of their students and aligned with the resources available at the SBHC. For example, SBHC staff can arrange tours of the health center or organize lunchtime education sessions with relatively limited resources while still reaching a large number of students. When more funding is available, SBHCs can hire staff focused on outreach, such as health educators to facilitate sexual health curricula in classes and connect students to SBHC services, or a social media coordinator who can engage with students on virtual platforms. We spoke with practitioners from SBHCs that had invested in more intensive outreach strategies who felt that their efforts had ultimately been “worth it” and had increased utilization of family planning services.

While the strategies highlighted in this brief have been successful for some SBHCs, there are a few important caveats. SBHCs may need to tailor strategies to be responsive to the populations of students they serve—for example, by offering materials in different languages; using inclusive, LGBTQ-friendly language; and aligning parent consent rules with SBHC and state policies. Furthermore, confidentiality is a major concern for many adolescents and may prevent some from seeking needed family planning care. When sharing information about the SBHC through in-class presentations or on social media platforms, it is important that SBHCs describe how they protect confidentiality and privacy.

The next phase of our work will create an online toolkit for practitioners to provide more information on a variety of strategies for providing family planning services in school-based settings. In the meantime, we hope the strategies presented in this brief spark ideas among practitioners in developing innovative outreach strategies. For information on related work, see our partnerships brief, which describes strategies that school-based providers have used to identify and leverage new and existing partnerships to improve access to family planning services among students.

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the Office of Population Affairs for supporting this research under grant FPRPA006065. We would especially like to thank our project officer, Callie Koesters, for her leadership. The authors also thank the School-Based Health Alliance for their partnership on the project, and especially for their assistance in connecting us to practitioners to interview. Further, we thank Andrea Shore and Katherine Cushing of the Alliance for their review of the brief.

This brief would not have been possible without the assistance of many colleagues at Child Trends who contributed to the interviews and analyses, including Andrea Vazzano, Elizabeth Cook, Hannah Lantos, Elizabeth Wildsmith, Sydney Briggs, Anushree Bhatia, and Huda Tauseef. We additionally thank Brent Franklin, Jody Franklin, Tina Plaza-Whoriskey, and Kristen Harper for their reviews; Catherine Nichols for her design work; and Ria Shelton for her fact check. Finally, the authors are deeply grateful to the practitioners who offered their time and critical perspectives to this research.

Download

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram