Integrating Positive Youth Development and Racial Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging Approaches Across the Child Welfare and Justice Systems

Over the past 30 years, a growing body of research has indicated that Positive Youth Development (PYD) approaches can improve mental and physical health, education, and employment outcomes for young people. PYD approaches focus on young people’s assets and build on protective factors such as family and social supports to enhance positive, age-appropriate development. Despite the promise of PYD approaches, child welfare and justice systems have struggled to adapt them in a way that systematically focuses on protective factors; leverages youth, family, and community strengths across multiple domains; and coordinates with other systems in which youth are involved (i.e., education or employment training).

According to the most recent Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) data, in 2019, there were 423,997 children in foster care, 16,959 of whom were ages 18 to 21 and aging out.1 In the same year, 237,000 young adults had cases processed by the juvenile justice courts.2 Data have documented the disproportionate number of Black, American Indian, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ youth in child welfare and justice systems, and that the negative outcomes experienced by these youth have not improved over time, despite multiple efforts devoted to this issue. The racial disparities reflect historic and systemic racism, as well as other factors, that need to be addressed for a more equity-centered approach in these systems.

According to the most recent Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) data, in 2019, there were 423,997 children in foster care, 16,959 of whom were ages 18 to 21 and aging out.1 In the same year, 237,000 young adults had cases processed by the juvenile justice courts.2 Data have documented the disproportionate number of Black, American Indian, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ youth in child welfare and justice systems, and that the negative outcomes experienced by these youth have not improved over time, despite multiple efforts devoted to this issue. The racial disparities reflect historic and systemic racism, as well as other factors, that need to be addressed for a more equity-centered approach in these systems.

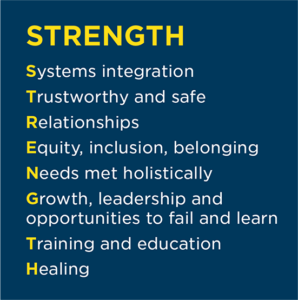

In this working paper, we explore why these systems need a new emphasis on PYD approaches that incorporate racial equity and inclusion, why it is important to focus on young adults specifically, and why the child welfare and justice systems are particularly important sectors in which to provide positive, developmentally appropriate supports. This paper also introduces “STRENGTH” (see box, and the graphic depiction in the Conceptual Framework section), a conceptual model structured around eight principles drawn from PYD frameworks that can be used by programs and communities to guide and collaborate in supporting adolescents and young adults in both child welfare and justice systems. The word “STRENGTH,” as the representation of these principles, should remind program administrators, staff, and others working with young adults of both the need to build strengths and of the inherent strengths that young adults bring to their situations. A strengths-based approach that centers these positive characteristics, rather than a young adult’s deficits, underlies all eight principles. Further, these principles give public systems a roadmap to reevaluate how they approach youth and families in a way that invokes PYD principles, is explicitly focused on equity and inclusion, and is centered on communities and families.

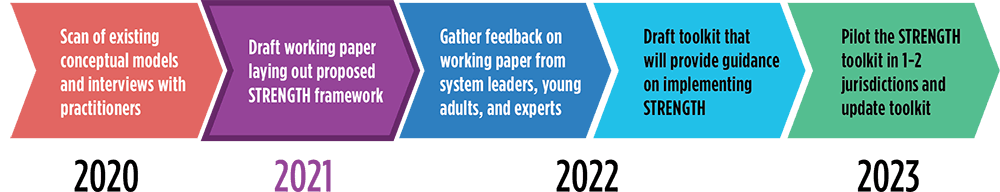

The working paper concludes with a discussion of the next phase of our work—a toolkit intended to provide concrete supports to programs and systems that are adding or building on PYD approaches for young adults (see the figure below showing the timeline). To gather feedback on the “STRENGTH” principles from stakeholders, we are including a feedback form and a place for others to identify important resources that could be useful to share. We will use the feedback to guide our approach to creating the toolkit.

Please share your feedback through our STRENGTH Principles feedback form.

A Principles-based Toolkit to Support Systems-involved Youth Transitioning to Adulthood

The child welfare and justice systems have had only sporadic and infrequent success with improving outcomes for older adolescents and young adults. Longitudinal data confirm that youth who interact with those systems have difficulty adjusting and living healthy, fulfilling lives. These outcomes are even more prominent for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning) youth. The lack of supports available and accessible to older youth in these systems, in which large racial disparities also persist, has received more intensive attention in the last two years. Staff in public systems were already grappling with how the policies and practices designed to protect young people have actually inflicted harm on them, their families, and their communities. Fueled by the escalation of racial tensions due to violence committed by police, especially against Black Americans, and the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, public systems began to express more urgency around needed reforms and on the need to engage in more intentional conversations around anti-racism.

While systems have been slow to take up PYD approaches, the case for change has been growing:

- Groundbreaking research in adolescent brain science, youth development, and trauma has helped the field understand how youth and young adults mature and interact with the world, and more thoroughly appreciate the need for age-appropriate support and resources to foster their positive development.

- Experts and advocates have called for the reduction of congregate care, supported by growing research that documents lasting negative effects on a young person’s development and well-being when they are removed from their families and communities.

- Strength-focused or positive youth frameworks, such as Youth Thrive and Positive Youth Justice, have been integrated into the practices of some child welfare and juvenile justice systems providing services.

- Research highlighting the perspectives of young people from organizations—such as Chapin Hall, Foster Club, and Think of Us—have put a human face and voice to the challenges and harms of systems involvement.

- Data have documented the disproportionate number of Black, American Indian, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ youth in child welfare and justice systems, and that the negative outcomes experienced by these youth have not improved over time, despite multiple efforts devoted to this issue.

- Generation Work, an initiative funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (the Casey Foundation), has found that including equity-oriented PYD practices in programs to provide education and employment opportunities to youth and young adults resonates strongly with participants.

- Since 2001, the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, an initiative of the Casey Foundation, has worked to ensure that young people ages 14 to 26 who have spent at least one day in foster care after age 14 are supported in getting the resources, relationships, and opportunities across multiple systems that they need to achieve well-being and success.

Researchers from Child Trends and Child Focus Partners joined staff from the Casey Foundation, along with young adults with lived experiences in the child welfare and justice systems, to collectively develop the eight STRENGTH principles. We note that these are principles, and not a program or curriculum; hence, they can be implemented in a variety of settings with varied populations. The team will use feedback on this working paper as we develop a toolkit with resources on integrating the STRENGTH principles into work that supports youth and young adults. When practiced, these eight core principles can help systems implement better solutions to support young people. Because PYD is a set of principles and not a specific program or curriculum, the STRENGTH principles and associated tools can be used across government systems, with local communities and families, and within multiple contexts to promote and build the strengths of young people. These principles provide a roadmap to evaluate (or reevaluate) how systems approach youth and families in a way that invokes PYD principles, is focused on equity and inclusion, and is centered on communities and family.

Identifying the STRENGTH principles and developing the toolkit are part of a recent commitment by the Foundation to dedicate at least half of its investments over the next decade to improving the well-being of youth and young adults. By working with young adults and communities, the Foundation seeks to ensure that all young adults have the family connections, relationships, connections to communities, and education and employment opportunities they need to Thrive by 25.1 While the Foundation has worked for years to invest in public systems reform, this recent focus acknowledges that communities and government systems have assets that help young people thrive, but need tools to align their work across a common youth-centered framework.

Youth and their families connect to both informal and formal community networks of service providers, educators, bodies of faith, elders, and other important cultural figures. No two communities will have the exact same set of actors, and many will prefer approaches that exist outside of traditional government service delivery models; however, it is critical to engage a broad array of actors around a common framework. When community stakeholders are engaged in processes and have needed resources, they can address community issues and develop effective approaches that prevent harmful systems involvement or better support families when systems involvement is unavoidable.

The outcomes of using STRENGTH principles will vary based on the contexts and systems in which they are implemented. However, possible outcomes of integrating an equity-focused PYD approach include the following:

- Young people will remain with their families whenever possible; separation, when needed, will be less frequent and for shorter periods.

- Young people will work with their communities, programs, and systems in co-designing supportive programs and practices.

- Systems will set explicit goals for decreasing racial disparities in rates of separation, placement, and incarceration.

- Systems will focus more on healing and reconciliation and less on punishment and blame.

- Families and communities will be better equipped to work together to address young people’s needs, both before and after systems involvement, so that government entities will be less involved.

- Systems will have more common, positive, and inclusive approaches when serving young people.

- Young people will be better prepared for education, the workforce, and life events as they happen.

- Families will know better where to turn for help when needed.

Centering adolescents’ and emerging adults’ transition needs

The period from age 16 to the mid-20s (emerging adulthood) is a time in which educational and employment skills are honed, friendships and romantic relationships are formed, and longer-term goals and trajectories are embarked upon. This life stage involves identifying and reaching professional and/or educational goals, developing and changing relationships (with peers, family, and romantic partners), and becoming more self-sufficient and independent (economically and socially). For some young people, this life stage also involves becoming parents themselves. The experiences, opportunities, and choices that occur more regularly within this age range enable youth to develop financial and social independence from their biological families and parents and can have long-term impacts later into adulthood. While this financial independence has been more difficult to achieve following the 2008 recession and during the COVID-19 pandemic, it still often represents a key skill for young adults to develop. Jeffrey Arnett, the researcher who coined the term “emerging adulthood,” writes:

Emerging adulthood is distinguished by relative independence from social roles and from normative expectations. Having left the dependency of childhood and adolescence, and having not yet entered the enduring responsibilities that are normative in adulthood, emerging adults often explore a variety of possible life directions in love, work, and worldviews. Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future has been decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course.

While cognitive development affecting logic and reasoning develops during the teenage years, psychosocial maturity (for example, self-control) continues to mature well into the twenties. This “maturity gap” necessitates opportunities to promote self-regulation, resilience, and healthy relationship building for young adults. The effects of this gap can be exacerbated by trauma. For example, neglect and maltreatment can lead to complex attachment issues and poor health and educational outcomes, among other negative outcomes. However, when the programs or the environments in which young adults find themselves (such as educational campuses and the workforce) incorporate PYD approaches, adolescents can learn to grow and take reasonable risks with some degree of safety and guidance.

Under ideal circumstances, healthy development means that young adults get to test out independence while still knowing they have people they can rely on when needed. However, youth who transition into adulthood while involved in (or with previous involvement in) the child welfare or juvenile and/or criminal justice systems3 often do not have the luxury of a safety net. They often experience challenges to becoming healthy, self-sufficient, and well-adjusted adults. Their life circumstances and their behaviors drive some of these challenges, but others are driven and exacerbated by the systems in which they are involved. Specifically, the child welfare and the juvenile and criminal justice systems often do not allow emerging adults to test their independence in healthy and positive ways; to create trusting and consistent relationships with peers, mentors, or family members; or to develop the skills and seek out the experiences that are needed in emerging adulthood.

Demographics of the populations involved in the juvenile and criminal justice and child welfare systems

Child welfare

Children and youth enter the foster care system for a variety of reasons, including maltreatment, neglect, parental substance abuse, and inadequate housing. In 2019, 64 percent of children entered the system because of neglect, with an additional 38 percent entering as a result of parental substance abuse (some report both). The number of children and youth (birth to age 20) entering the foster care system is approximately 250,000 to 270,000 annually, with the overall number in the system at any given time around 430,000—both numbers having remained fairly steady since 2010. Lower-income parents are more likely to be reported and investigated, and to have their children placed in the foster system. This is due to a combination of biases against lower-income people and a lack of accesses to resources such as housing and adequate care resulting in children being reported for neglect.

Children and youth who enter foster care may exit the system for many reasons, including adoption, reunification, emancipation, or aging out. In 2019, more than 20,000 young people aged out when they turned 18 years old without access to adequate supports and services. Although some states provide extended care services, allowing youth to stay and receive transition services until they reach age 21, many young adults do not receive these services.

Black, American Indian, and LGBTQ+ youth and young adults are overrepresented in the foster care system, while Asian, White, and Hispanic children tend to be underrepresented. Black and American Indian families are more likely to be reported for maltreatment and neglect. They are also more likely, once reported, to undergo investigation, and their children stay in the foster care system for longer periods of time, on average. Finally, these children are less likely to exit the child welfare system through reunification or adoption, which tend to be the most stable outcomes for exiting young people. Each of these disparities is a consequence of the child welfare system’s historical and current biases that have resulted in racist practices. These practices, in turn, lead to child welfare or juvenile justice placements for too many teens who simply did not belong in these systems but whose communities had insufficient alternatives to help families resolve conflicts, obtain needed resources, or address teens’ behavioral health issues.

Juvenile and criminal justice

Juvenile justice system involvement has been declining since 2006. However, involvement in the system is not evenly distributed across all young people. Youth of color are more likely to be incarcerated than their White counterparts. Black youth are almost five times more likely than White youth to be incarcerated, while Latinx youth are twice as likely and American Indian youth are three times as likely. In addition, LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to be arrested and make up 13 percent of those who are detained. Homelessness and unaddressed mental health issues also put youth at risk of encountering the juvenile justice system.

Youth involved in the juvenile justice system often have histories of trauma, neglect, abuse, community violence, and complex caregiver trauma. In addition to, or because of, these exposures, they struggle with effective emotion management and regulation, putting them at great risk for reckless behavior, delinquency, substance abuse, and susceptibility to negative peer pressures as they struggle to survive the symptoms of their childhood traumas. In addition, many young people face ongoing challenges once they are detained. For example, a 2014 report from the U.S. Department of Justice reported that nearly half of incarcerated youth were placed in solitary confinement for at least four hours during their incarceration, a fact further exacerbated by COVID-19. Solitary confinement can immensely impact young people, and has been found to lead to depression, psychological harm, and suicide—and can impede brain development.

Understanding the specific needs of systems-involved adolescents and emerging adults

Young adults with experience in the child welfare or justice systems face numerous challenges. Many have been removed from their homes, and systems-involved youth experience higher levels of surveillance than youth outside of systems, putting them at greater risk of punishment through these systems. Some have faced significant disruptions to schooling or community connection following removal or disorientation as they get used to new settings or places. Young people in these situations often struggle with identity-formation or do not feel safe, given their level of instability and their receipt of conflicting messages about who or what is safe and loving. Many need to develop skills to heal previous relationships in which trust was broken or to develop new relationships. Additionally, young adults with a history of child welfare and/or juvenile or criminal justice systems involvement often do not have supports or resources in place to meet urgent needs, including housing, health care, employment, food, or clothing. While having fewer financial resources can drive some of these challenges, many young adults with systems involvement also have smaller social networks, fewer adults paying attention to them and their needs, and fewer people to advocate on their behalf. Redundant, uncoordinated, or ineffective services are common, and some of their needs go completely unmet. Following these difficult experiences, young adults often struggle to navigate their experiences of disruption, mistreatment, or lack of support and fail to make a healthy transition to adulthood. Ongoing involvement in the child welfare and/or justice systems often further exacerbates this trauma through overly punitive, reactive, and uncompassionate interactions.

Any of these experiences alone could undermine a young person’s ability to successfully transition to adulthood, but combined, they make this transition significantly more difficult. Systems serving young people have a moral and financial responsibility to set young adults on a successful trajectory. This imperative has, or should have, a direct impact on young people themselves, as well as indirect impacts on their families, peers, children, communities, and others.

While some of the shifts toward PYD approaches that we propose through the STRENGTH approach (below) may have higher upfront costs, a young adult who has more mature relationships and is more self-sufficient will contribute to society, their families, and their communities long into the future. A young person who does not have such relationships and who is not self-sufficient may, instead, increase societal costs long into the future through use of benefits programs, additional incarceration, or harm done to others. Additionally, investing in communities and programs with a focus on our proposed principles rather than spending money on the expensive and often ineffective residential programs that break apart families and communities, provides an opportunity to prioritize the youth and their communities.

There are two additional reasons that incorporating PYD approaches is essential. First, young people in these systems are often overly controlled (e.g., where they can go or with whom), while they are simultaneously expected to be independent (e.g., able to keep track of multiple demands on their time). Systems must recognize that all adolescents and young adults need support, in addition to opportunities to incrementally increase their level of independence. Moving from complete control in a residential facility to being completely on one’s own would be challenging for any young person. Second, coordination is critical, as young people in these systems often come into contact with multiple systems that are not integrated and have redundant or even unhelpful requirements (e.g., weekly therapeutic sessions with a counselor in each system). The reasons that drive the need for coordination are discussed in more detail in the appendices and at least one of the letters in the STRENGTH principles directly focuses on these reasons.

Research Review and Background Research

In late 2019, the Casey Foundation gave funding to Child Focus to do a landscape scan of PYD frameworks and practices to identify common elements across multiple sectors that could both promote positive youth outcomes and be applied to programs and systems that serve child welfare and/or justice system-involved youth. This scan included a review of 14 youth development frameworks (listed in Appendix B) and interviews with program practitioners, public system administrators, researchers, and framework developers. Details of both the landscape scan and the frameworks are included in Appendix A for those who want more information.

Defining and identifying strategies for implementing the eight STRENGTH Principles

The principles defined by the word “STRENGTH” capture themes we identified from both the practitioner interviews and from existing research and frameworks about key strategies and principles of PYD. The use of the word “STRENGTH” is meant to make the principles approachable and easy to remember. Practitioners use a wide variety of terms to talk about the work that they do. STRENGTH is meant to be a tool that systems can use in two ways as they begin to work together more closely. First, it can help systems identify and agree upon their common underlying principles. Second, it can ensure that systems use common language to describe their approaches. Systems must work with youth, with other systems, and with youths’ families and communities to find ways to support young people. In addition, systems must all exemplify equity and provide services that are trustworthy and safe while meeting the basic needs that youth may have as they emerge into adulthood. Without this common set of principles and the coordination to act on them, youth who are involved in or leaving public systems will continue to be poorly served.4

The eight principles that make up the word “STRENGTH,” listed on page two, are discussed further below. They reflect the core principles of PYD that, when enacted by systems, can serve young adults in positive and developmentally appropriate ways.

Eight PYD principles: STRENGTH

S: Systems integration. To affect the lives of young adults, all actors should work within the broader ecosystem in which young adults exist and which includes families, communities, and government systems. Systems that serve young people must develop processes, data systems, a common language, and support structures that collectively meet young adults’ needs and integrate families and communities into their work. Systems integration can also reduce the number of conflicting rules faced by youth and the number of staff a youth encounters, which can allow staff and youth to build and sustain trusting relationships. It is also fundamental that this coordination be carried out with the intent to center youth and young adults, and/or be driven by them. The PYD framework promotes youth-centered approaches that give youth power to affect their environment and make choices that fulfill their goals, which lead to positive youth outcomes.

T: Trustworthy and safe. Programs and systems must ensure that the spaces in which young adults live and learn are not only physically safe but also emotionally and psychologically safe. Youth and young adults should feel that they belong, and should feel supported in expressing their feelings, needs, and desires as they heal and overcome past traumas. Without addressing young people’s socioemotional needs, systems risk causing further damage and increasing the risk that another generation of families will cycle through their doors. Furthermore, one part of creating conditions of safety for youth is for them to safely learn independence.

R: Relationships. Positive and supportive relationships with older adults, peers, and families can help young adults achieve their goals and navigate the complex decisions that are part of their transition to adulthood. Systems must be aware of how positive relationships are crucial to a young person’s identity and sense of belonging, and that supportive relationships in young people’s birth families and communities are vital to their success.

E: Equity, inclusion, and belonging. Because of historical and systemic racism and bias, BIPOC and LGBTQ+ youth are disproportionately involved in both the child welfare and justice systems. These systems must commit to going beyond equality of services to assuring that outcomes are equitable. While it is essential to specifically call out racial equity, systems serve young adults of different races/ethnicities, genders, religions, ages, sexual orientations, and life experiences; each of these identities must be considered in an equity approach. To achieve good outcomes, systems must embrace the importance of history and culture as essential elements in identity formation for youth and young adults. As highlighted by Child Trends researchers, “Embedding a racial equity perspective means making a conscious effort to identify and address systemic barriers that impede the healthy development of children and youth of color. Racial equity is achieved when race is no longer a predictor of young people’s experiences and outcomes.”

N: Needs are met holistically. Young adults in the child welfare and/or criminal or juvenile justice systems must often be relentless self-advocates to get their needs met. Systems must support young adults’ access to comprehensive supports that meet their physical, emotional, and planning needs as they transition into adulthood. Ensuring that young adults’ needs are met and that they have help and support to navigate challenging processes will often require cooperative work across siloed systems, and with families and communities.

G: Growth, leadership, and opportunities to fail and learn. Young adults need opportunities to learn, grow, try, fail, and try again. Emerging adulthood is a critical developmental period associated with many new risks and new opportunities. Learning to engage with reasonable risks and opportunities in healthy ways can create experiences that help young people learn to navigate challenges, communicate with others, ask for help, and try again. It is only by overcoming challenges and achieving new objectives that young adults can assert their independence and gain confidence to make their own decisions. For young people involved in the child welfare and/or justice systems, failure means deeper systems involvement and more surveillance. Systems-involved youth often grow up without the ability to dream big, or they become fearful of taking even small risks when previous mistakes have resulted in a mark on their record. Systems need to provide space for young people to make mistakes without such penalties.

T: Training and education. Training and education for young adults are key to their economic mobility. Learning opportunities can focus on helping young people develop academic, technical, executive functioning, or soft skills. Young people need access to education and career paths in marketable industries. Compared to their peers, systems-involved youth are at a disadvantage in attaining education and training opportunities. Opportunities for training and education should help young people identify their goals and develop agency to meet those goals. In communities where opportunities to learn and train for good jobs can be limited, programs, communities, and other adults must pay attention to creating these opportunities for all young adults. Giving young people marketable skills and—by extension, access to earnings, assets, and wealth—can benefit the individual and their community.

H: Healing. Many young people involved in systems (such as juvenile justice or child welfare) have experienced harm or trauma. When a young person has not dealt with unhealed trauma and hurt from their past, it inhibits their ability to form stable, trusting relationships with others or manage their emotions—both of which are vital to their success. It is essential to ensure that systems are intentionally restorative, healing, and trauma-informed. Systems should focus on the young person and look beyond deficits to see their strengths. Young people of color are also experiencing compounded trauma as a result of generational trauma inflicted upon their families and communities, caused by racism and discriminatory policies. To think about healing broadly, systems must shift toward investing in young people’s well-being and assisting with healing broken relationships, fractured families, and communities.

Conceptual Framework

Related Content

- Using Photos to Capture Young Adults’ Experiences with Positive Youth Development

- Latino and Asian Households Were Less Likely to Receive Initial COVID-19 Stimulus Payments, a Trend That Reversed for Later Payments

- Early in the COVID-19 Pandemic, Latino and Low-Income Households With Children Were Less Likely to Receive Unemployment Benefits

- Integrating a Racial and Ethnic Equity Lens into Workforce Development Training for Young Adults

- The PILOT Assessment: A Guide to Integrating Positive Youth Development into Workforce Training Settings

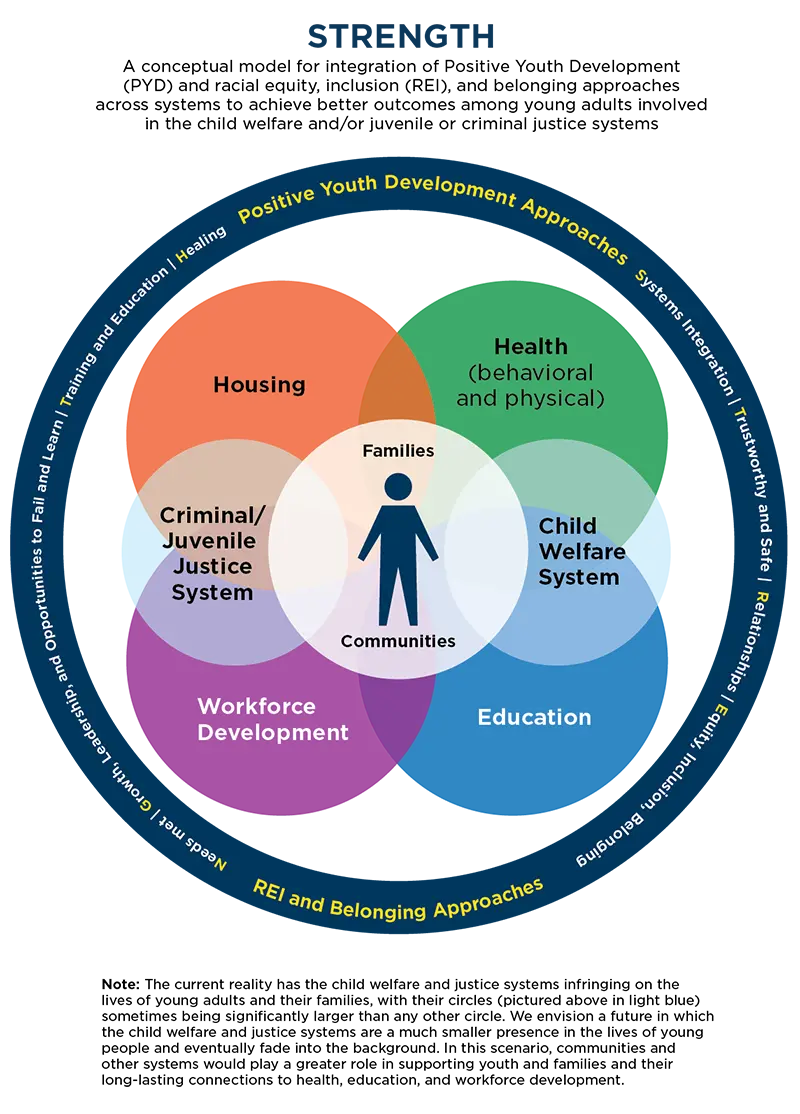

The conceptual framework presented above depicts how programs within systems can work together to enact PYD and anti-racism practices.

Starting in the center, the framework depicts a young adult standing in the middle of many circles representing the systems and communities with which a young person might interact. This figure is placed in the center to remind programs and systems that the young person should always be the focus. Programs and systems should center youth and young adults in all that they do. Families and communities surround the young person in that center circle as well.

Two of the six circles in the framework—the child welfare and criminal or juvenile justice systems—appear in the front, “on top” of the other four circles. Behind these two circles are four colorful circles that represent four additional systems: education, health (both physical and behavioral health), housing, and workforce development. Each system overlaps to some degree to indicate that these systems must coordinate to effectively serve young adults. The circle with the young adult overlaps with all other circles to indicate their potential involvement in any or all systems at any given time. Finally, surrounding the entire set of circles is another circle which says, “Positive Youth Development Approaches” and “Anti-Racism Approaches.” These approaches are driven by the eight principles of PYD that we defined earlier using the word “STRENGTH.”

Implementing STRENGTH

Step one in implementation is defining a common set of positive values and principles. Fortunately, a steadily accumulating body of research indicates the value and effectiveness of PYD approaches in programs that support adolescents and young adults. There is no shortage of frameworks to embed PYD within systems; however, most systems struggle with operationalizing those frameworks into their practice, policy, and outcomes. Many of the existing frameworks are excellent options for child welfare and justice systems, but most lack implementation tools that system administrators can easily adapt to change system culture and impact outcomes. Because PYD and REI represent practices or approaches, rather than programs or curricula, they have the flexibility needed to work across systems.

Step 2 is to ensure that PYD approaches aligned with REI are an integral part of how systems work and are implemented consistently. For example, systems must make youth themselves their first priority. Systems must also recognize the strengths that youth hold and focus on building youths’ technical, social, emotional, and soft skills. Young people in these systems have often faced disconnection from their communities and families—the very people and institutions that would typically help a young person acquire varied skillsets. The STRENGTH principles are designed to leverage current frameworks, practice models, and practices. Ultimately, the accompanying toolkit will give systems the tools they need to meaningfully implement these frameworks in partnership with communities to measure their success and hold themselves accountable. As noted, the STRENGTH principles are not meant to be implemented only in one setting or in one program type; instead, they are meant to be applicable to a wide variety of settings. In this way, the word principle was chosen intentionally rather than the word practice. The eight STRENGTH principles are meant to guide practices across settings.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Despite the promise that PYD approaches provide, teenagers and young adults who are engaged in the child welfare or justice systems (or both) often have not received positive, developmentally appropriate supports in settings that emphasize equity. Systems have struggled to incorporate racial equity approaches even though REI practices are aligned with the science on adolescent brain development, the science on social development, and approaches that are more equitable and healing. The STRENGTH principles provide a comprehensive and cohesive approach that builds on existing frameworks and expertise in the field while adding in a systems and racial equity frame.

As mentioned, this document and the STRENGTH principles are being released in this working paper because we’d like your feedback on the PYD and REI approaches identified. Ideally, your feedback will address whether the background and principles set the stage in logical and appropriate ways for increased use of PYD and REI approaches to serve system-involved young adults. Our goal is to use this feedback to draft a toolkit by Fall 2022 that collects existing tools and resources around how to implement this work. The toolkit will provide more guidance on day-to-day implementation of the STRENGTH principles. Once the toolkit is drafted, we plan to pilot it in one or two jurisdictions and adapt it based on feedback.

Appendix A: Results of Landscape Scan and Practitioner Interviews

Appendix B: Frameworks Reviewed

Appendix C: Shifting Systems’ Focus to Center Youth

Footnotes

Authors

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube