Will Recent Progress in Academic Achievement Translate into Broader Gains in the Well-Being of Hispanic Youth?

With the school year just begun, the U.S. reaches a watershed: for the first time in our history, racial minorities comprise the majority of students in public schools. How our schools, our other institutions, and we as individuals respond to this new demography will have much to say about our shared future.

The largest of these minority groups is Hispanic/Latino—a category of great diversity in itself. Today, one in four U.S. children is Latino; by 2050, it will be one in three—about the same proportion who will be white/non-Latino.

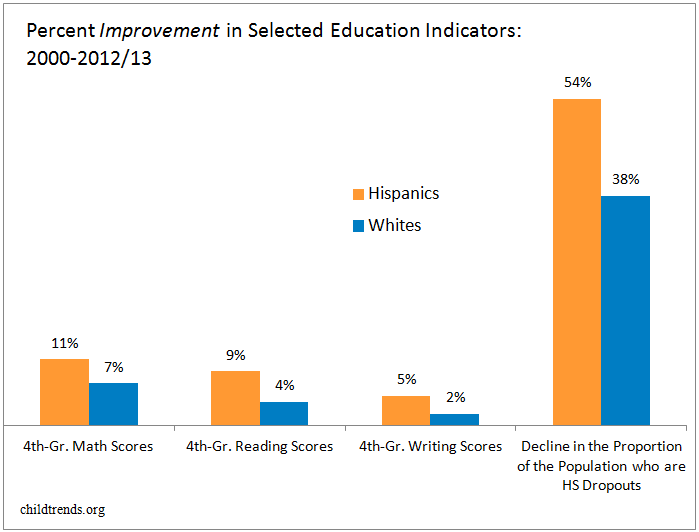

As Child Trends’ report, America’s Hispanic Children: Gaining Ground, Looking Forward, shows, the recent progress of Hispanic children in America—particularly in the area of education—is remarkable on its face.

The share of Hispanic high school graduates immediately enrolling in college is up by 41 percent between 2000 and 2012.

It is even more remarkable when we consider that Hispanics constitute the largest minority group of children in poverty (the rate of poverty is higher among black children, but the number of Hispanic children is greater). Nearly one-third of Hispanic children live in families with incomes below the poverty level, and a similar proportion in families which, while not technically poor, have incomes barely adequate to get by on.

Yet, if schooling is the ticket to economic success in America, minority students’ achievement in education has been a decidedly mixed bag. Despite a nearly continual parade of education reforms over the past decades, serious achievement gaps persist—not only by race/ethnicity, but by family income. So, education is a leaky pipeline, which students enter unequally prepared, and where those disparities often persist, or even widen, over time. Education may be the best equalizer we’ve got, but it could be a lot better.

In addition to poverty, as a group Latino children and youth disproportionately experience a number of poor health outcomes (for instance, high rates of obesity, symptoms of depression, and teen pregnancy). Some of their families struggle with the experiences that have always accompanied immigration: separations from relatives, the need to master a new language, and challenges to maintaining valued traditions (including their heritage language).

The U.S. is certainly not unique among developed countries in experiencing rapid demographic change in the past few decades. However, our history suggests we should have an advantage in accommodating the shifting composition of our population: after all, we were founded as a nation of immigrants. Education is often cited as the primary driver of economic mobility—and of acculturation into mainstream society. But a focus on schools, while important, probably won’t be sufficient to address fully the inequities our Hispanic children face—that extend to health, neighborhoods, and economic opportunity.

And what will mainstream even mean, anyway, when we become a “majority minority” nation? Today’s demographics ask all of us to embrace the new tableau of diversity, perhaps to move beyond old (dis)comfort levels with cultural differences. We’ve done it before; we can do it again. More than ever, we need all-in strategies if our economy, and our broader social bonds, are to stay strong and thriving as we look ahead to the future we will share.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube