Supporting Older Youth Beyond Age 18: Examining Data and Trends in Extended Foster Care

During the transition from adolescence to adulthood, youth achieve important developmental milestones, such as learning decision-making and coping skills and becoming more independent. Older youth often rely on family and other supportive adults to help them during this transition by providing guidance as well as a financial and emotional safety net. However, these supports are often unavailable to older youth who are leaving the foster care system. Older youth who age out of foster care are at increased risk for several adverse adult outcomes, including homelessness, high unemployment rates, low educational attainment, and early or unintended pregnancies. Extended foster care is one tool to lessen these risks by providing older youth with the opportunity to receive services and establish permanent connections with supportive adults prior to leaving the foster care system. While most states offer some version of extended foster care, utilization among older youth remains low across the country.

Extended foster care allows older youth to stay in care past age 18[a] and receive needed services and supports to aid in the transition to adulthood. With the support of the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, Child Trends examined the relationship between extended foster care and young adult outcomes. Specifically, we analyzed information on foster care history (e.g., age of entry, exit reason, placement type), young adult outcomes ( e.g., homelessness, employment), and independent living services (e.g., educational aid). We also examined the relationship between extended foster care and several important outcomes. These outcome areas include emancipation rates, high school graduation/GED, employment outcomes, school enrollment (high school or post-secondary), disconnectedness (not being enrolled in school and not working), educational aid, homelessness, and young parenthood. This information is drawn from three national datasets: the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Foster Care File, the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) Services File, and the NYTD Outcomes File.

Key findings

- Extended foster care is associated with better young adult outcomes. Older youth in extended foster care at ages 19 and 21 experience better outcomes than older youth not in extended foster care.

- Even a small dose of extended foster care is associated with better outcomes. Older youth in care at age 19 but not at age 21 experienced better outcomes at age 21 in employment, high school diploma/GED completion, educational aid, homelessness, and young parenthood compared to their peers not in care at age 19.

- Extended foster care is associated with receipt of independent living services. Older youth in extended foster care are more likely to receive services, and receive more services, than older youth not in extended foster care.

- Permanency rates have remained largely stable after the implementation of extended foster care. Permanency rates for older youth remain steady in states that have extended foster care. Extended foster care does not appear to increase or decrease permanency rates and cannot replace a permanent, loving family.

- Older youth’s reasons for entering care differ from those of their younger peers. Older youth are more likely to enter care due to neglect or a behavioral problem than their younger peers.

- Older youth in care spend more time in foster care than their younger peers. Once in foster care, older youth spend more days in care than their younger peers.

Extended foster care is designed to help older youth transition to adulthood successfully, while allowing the child welfare system additional time to secure permanent family supports. While extended foster care utilization rates are still low in many states, extended foster care appears to benefit young people as they transition to adulthood.

Introduction

Nationally, 164,554 older youth ages 14 to 21 were in the foster care system in fiscal year (FY) 2017, making up nearly a quarter of the country’s overall foster care population.[1] A young person’s brain undergoes large developmental changes between the ages of 14 and 25. During this time, young people are exploring their sense of identity, seeking greater independence, and developing decision-making and coping skills.[2] Some challenging youth behaviors associated with these changes are developmentally appropriate; however, the child welfare system is not always prepared to handle the unique needs of older youth in foster care. In several important ways, older youth in foster care are different from younger children in care: Older youth spend more time in foster care than their younger peers, and the reasons they enter and leave the foster care system are different from those of younger children.[3]

Older youth in foster care age out, or emancipate, when no legal permanent connection—such as being reunited with family, adopted, or placed under the care of a legal guardian—is available to them by the time they reach the age of majority in their state. Older youth who age out of foster care experience an increased risk for homelessness,[4],[5] young parenthood,[6] low educational attainment,[7] high unemployment rates,[8] and other adverse adult outcomes. These disparate outcomes can result in profound personal and financial costs to older youth as well as broader societal costs.

In the last two decades, three major federal policies have been enacted to address the unique needs and experiences of older youth transitioning out of foster care. The first of these, the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (Chafee), provided eligibility guidelines for youth receiving independent living services. Chafee services support young people who are at risk of aging out and provide financial resources for needed independent living services up to age 21.[b] These services vary by jurisdiction but usually include financial education, mentoring, post-secondary preparation, and tutoring. Chafee also created the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD), which provides researchers and policymakers with administrative data on service utilization, and survey data on young people’s experiences transitioning out of foster care. These two data sources are referred to as NYTD Services and NYTD Outcomes, respectively. They include information about young people from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, providing the first national dataset on this population.

Almost a decade after Chafee, the 2008 Fostering Transitions to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act (Fostering Connections) became law, providing additional federal guidance and expanded funding to states that extend foster care past age 18. This enables older youth to remain in foster care through their 21st birthday if they are enrolled in high school or post-secondary education, employed or participating in an employment training program, or unable to meet these criteria due to a disability. Fostering Connections allows states to decide whether to use federal funds for extended foster care. By 2019, 28 states (including DC) had a federally approved extended foster care plan, and 21 additional states had a state-funded program.[9]

Finally, in 2018, the Family First Prevention Services Act (Family First Act) amended the age eligibility requirements of Chafee to include all youth ages 14 to 23 who are either in foster care or have aged out of care. Prior to this amendment, states could decide who was deemed at risk of aging out and therefore eligible for these services. This change is intended to encourage states to provide independent living services to young people regardless of their involvement in extended foster care.

These policies reflect the public’s increased understanding of the needs of older youth during the transition to adulthood in general and of the needs of older youth in foster care in particular. This shift can be attributed to the attention and interest generated by a growing body of research indicating that young people’s brains continue to develop until they reach their mid to late twenties.

Methodology and Data

We used three federally mandated national datasets for all analyses in this brief. The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Foster Care File is an administrative dataset that provides information on the foster care history of all youth in care during a federal fiscal year. The National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) Services File compiles administrative data on all youth who have received at least one federally funded independent living service. Finally, the NYTD Outcomes File utilizes survey data collected from older youth at ages 17, 19, and 21.[3] The young person must be in care at age 17 to participate in the survey, but they are not required to still be in care when they participate at 19 and 21.

To understand the unique experiences of youth in care, we examined 10 years of AFCARS data (FFY 2008-2017), focusing on the entry of young people ages 14 and over into care. Using this expanded database, we compared entry rates, reasons for entry, and the time spent in foster care for this population to their peers under the age of 14 in foster care. Next, we assessed the impact of extended care policies on permanency at the population level by constructing two cohorts of older youth ages 18 to 21 who exited care in a three-year period before and after extended care was implemented in their state.

To identify a cohort of older youth in extended foster care, we identified those older youth who were still in care during the month of their 18th birthday or the month after. Then we tracked those same older youth across years and identified youth who remained in care until their 19th birthday.[4] These older youth were considered to be in extended foster care. Older youth who turned 18 in care but did not remain in care were used as a comparison group. Descriptive statistics on this population were used to identify differences in permanency for the extended care population. Additionally, examining NYTD Services data for this group of older youth allowed for a comparison of service utilization by extended care status.

Finally, we used NYTD Outcomes survey data to assess the association between utilization of extended care and positive adult outcomes. We compared respondents who reported being in extended foster care at Wave 2 (age 19) and Wave 3 (age 21) to older youth who did not report being in care at either wave. We used logistic regression to examine young adult outcomes (dependent variable) and extended foster care utilization (independent variable) while controlling for race, ethnicity, and gender. We then used logistic regression to determine if the relationship between extended foster care and young adult outcomes was moderated by race/ethnicity.

Presentation of Findings

Older youth’s experiences in foster care differ markedly from their younger peers

The AFCARS Foster Care File provides data on all young people who are in foster care during a fiscal year. We used this information to better understand the unique experiences of older youth in foster care, comparing entry rates, the reason for entry, and length of stay for the populations in care over and under the age of 14.

Entry rates and entry reasons. Older youth differ from children under age 14 in the reasons they enter the foster care system. Older youth are more likely to enter care due to neglect or behavior issues (such as a conflict with their parent), while their younger peers are more likely to enter care due to physical abuse or parental substance use. While entry rates for children under age 14 have increased over the last five years, entry rates for older youth ages 14 to 17 have steadily decreased since the Fostering Connections Act was passed.

Length of stay in foster care. Once in foster care, older youth spend more time in care than their peers who enter care before age 14. This is true for both the average cumulative time in foster care (860 days vs. 547 days, respectively) and the average time during the most recent foster care episode (751 days vs. 513 days, respectively). The longer cumulative length of stay may be explained by the fact that older youth, due to their age, can spend more time in care. For example, the maximum length of stay for a 3-year-old child who has spent time in care is three years, whereas a teenager in care can have a much longer maximum length of stay, even if the proportion of the teenager’s life spent in care is similar to the younger child. Older youth’s comparatively longer stay for their most recent foster care episode is another indication that their experience in care is different from their younger peers. Spending more time in foster care is associated with decreased odds of achieving permanency,[10] indicating that the length of stay for older youth is too long and may contribute to an increased risk of emancipation.

Older youth in foster care have a different path to permanency

Permanency is defined as having a legal permanent connection to an adult caregiver. Children and older youth in care exit to permanency through reunification, adoption, or guardianship. Reunification occurs when a youth returns home to their family. Youth who are unable to return to their family can exit the system by being adopted or having a legal guardian appointed for them.[e] Using AFCARS data, we examined permanency outcomes for older youth and found that their permanency outcomes differ from those of children under the age of 14. While older youth exit to permanency about 54 percent of the time, they are far more likely than their younger peers to age out of care.[11] Despite the aforementioned policy changes, emancipation rates have remained largely consistent over time.

Permanency rates for older youth remain largely steady as states implement extension of care.

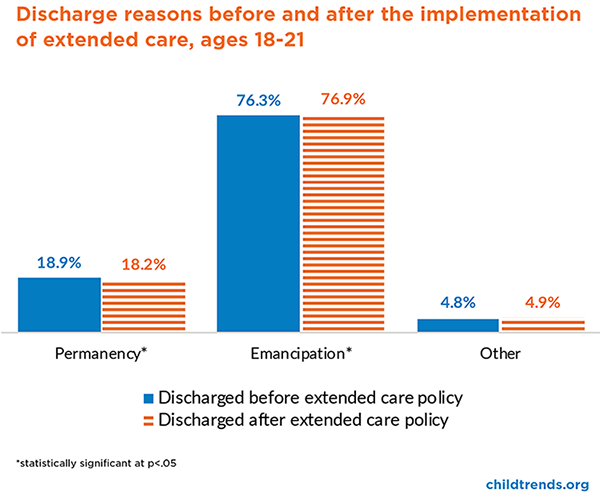

Among some stakeholders there was concern that extension of care would affect rates of permanency for older youth. To better understand the relationship between extended foster care and permanency, we compared permanency and emancipation rates in AFCARS for two cohorts of older youth (ages 18 to 21) in states with extended foster care funded through Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, which provides federal financing for the administration and support of the foster care system. One cohort consisted of older youth who exited care three years prior to extension of care in their state, while the other cohort included those who exited care in the three years following extension of care in their state.

This analytic design allowed for an examination of trends in permanency rates (for this age group) over a time period in which states implemented Title IV-E extended foster care. The graph below shows discharge reasons for the two cohorts. While there was a statistically significant difference between the groups of youth that were discharged before and after the extension of foster care, the proportion of youth emancipating remained largely stable. This may indicate limited practical significance in the change, in that states continue to see relatively the same proportion of older youth achieve permanency or emancipate from care before and after extended foster care. The current findings show that achieving permanency after the age of 18 is unlikely, underscoring that more research is needed to better understand the relationship between extended foster care and permanency.

Extended foster care is associated with better access to services

Extended foster care is associated with increased access to services and positive outcomes for older youth ages 18 to 21.[f] Our analysis of NYTD Services[g] data found that 65 percent of older youth in extended foster care through their 19th birthday receive services compared to only 35 percent of 18- to 19-year-olds who left care at age 18.

Although extended foster care does connect older youth to services, it is not the only path to receiving services. Older youth in extended care were more likely to receive services than youth who exited care, overall, but they were also more likely to receive a higher number of individual services for a broader service array. However, this gap in the number of services decreases if we consider older youth who were already participating in at least one service, regardless of their status in extended care. These findings indicate that older youth who are connected to services through extended foster care are those who might otherwise disengage from the child welfare system after turning 18; however, extended care does not have a large impact on older youth who are already connected to services after they turn 18. The findings also reinforce the importance of connecting youth to services early, while they are still in care, and reaching out often to ensure they receive needed and available services. Youth become eligible to receive independent living services at age 14 and should be receiving them throughout their time in care.

Extended foster care is associated with better adult outcomes

To assess the relationship between extended care and outcomes, we analyzed survey data for older youth ages 19 and 21 from the NYTD Outcomes File.[h] Using these data, we developed logistic regression models while controlling for race, ethnicity, and gender. We found that extended foster care is associated with better young adult outcomes in several key areas. Young people in extended foster care are more likely to achieve important young adult milestones such as finishing school and gaining employment than their counterparts who do not stay in care.

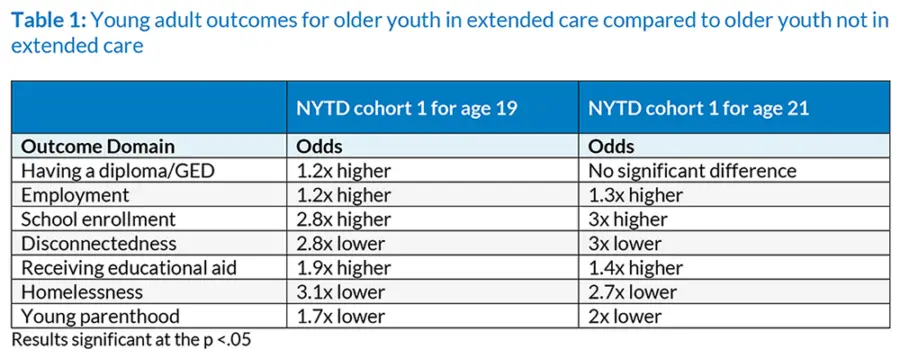

Specifically, our analysis indicates that older youth in extended foster care at ages 19 and 21 have higher odds of experiencing positive adult outcomes than their peers who leave care before age 19, and their peers who leave care before age 21. Older youth in care at age 19 have higher odds of being employed, being enrolled in school, and receiving educational aid when compared to their 19-year-old peers not in extended foster care. They also have lower odds of being disconnected (i.e., neither employed nor enrolled in school), being homeless, and having a child, compared to their peers who leave care before their 19th birthday (see table 1 for more details). Older youth who are in care at age 21 also have these better outcomes when compared to their peers who leave care before age 21. These findings suggest that extended care is helping to connect older youth to resources that enable them to gain the skills needed for a successful transition to adulthood.

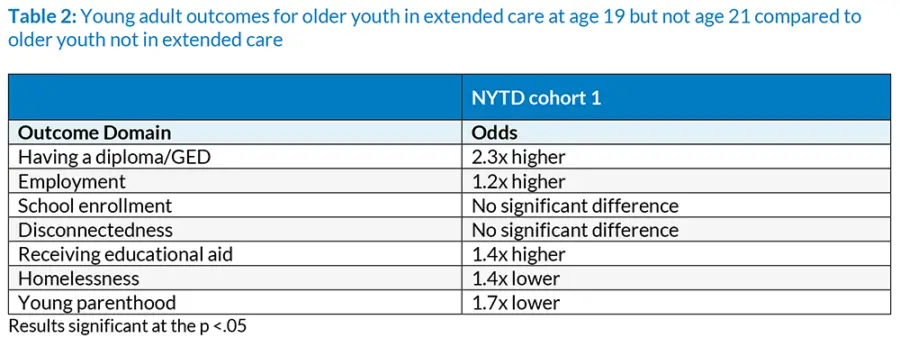

The analysis of adult outcomes is complicated by extended care eligibility requirements that often require young people to be enrolled in school or employed; these requirements may result in a decrease in positive outcomes once a young person is no longer involved in the child welfare system. To examine this potential backslide of outcomes, we analyzed the outcomes for older youth who were in care at age 19 but were no longer in care at age 21. The results of this analysis suggest that even a small dose of extended foster care is associated with positive outcomes. Compared to 21-year-olds without any extended care experience (measured in NYTD), older youth in care at age 19 but not at age 21 have higher odds of being employed, completing a high school diploma/GED, and receiving educational aid, and their odds of being homeless and having a child at age 21 are lower.

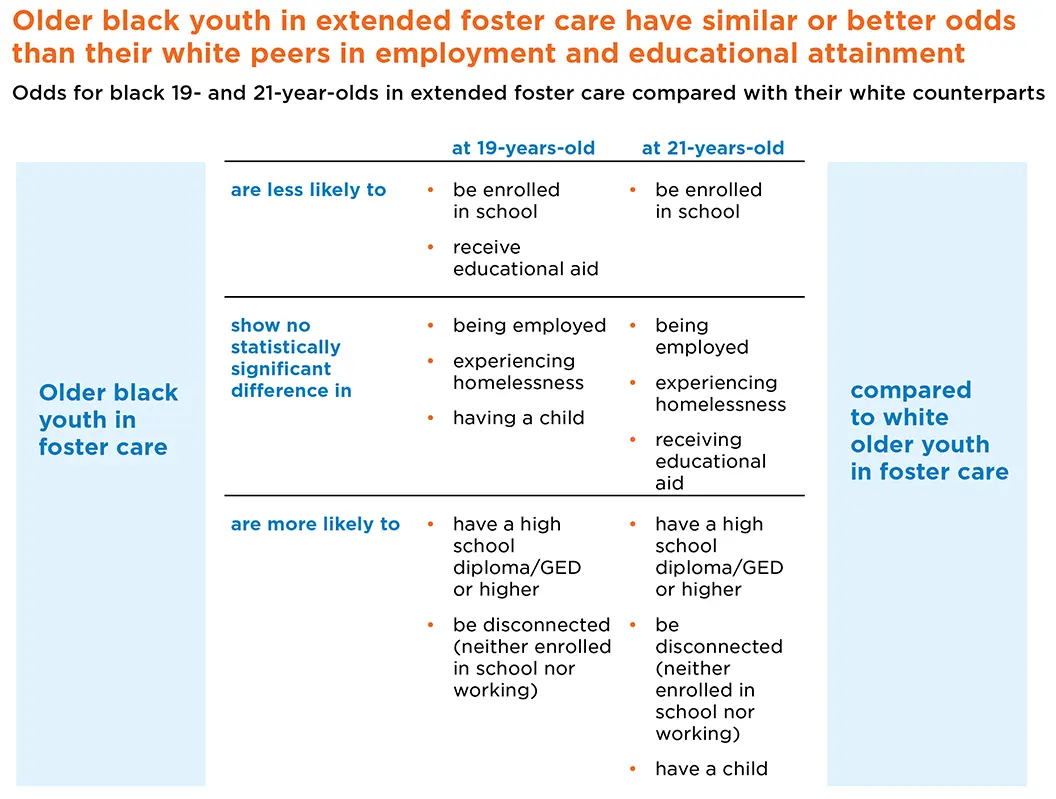

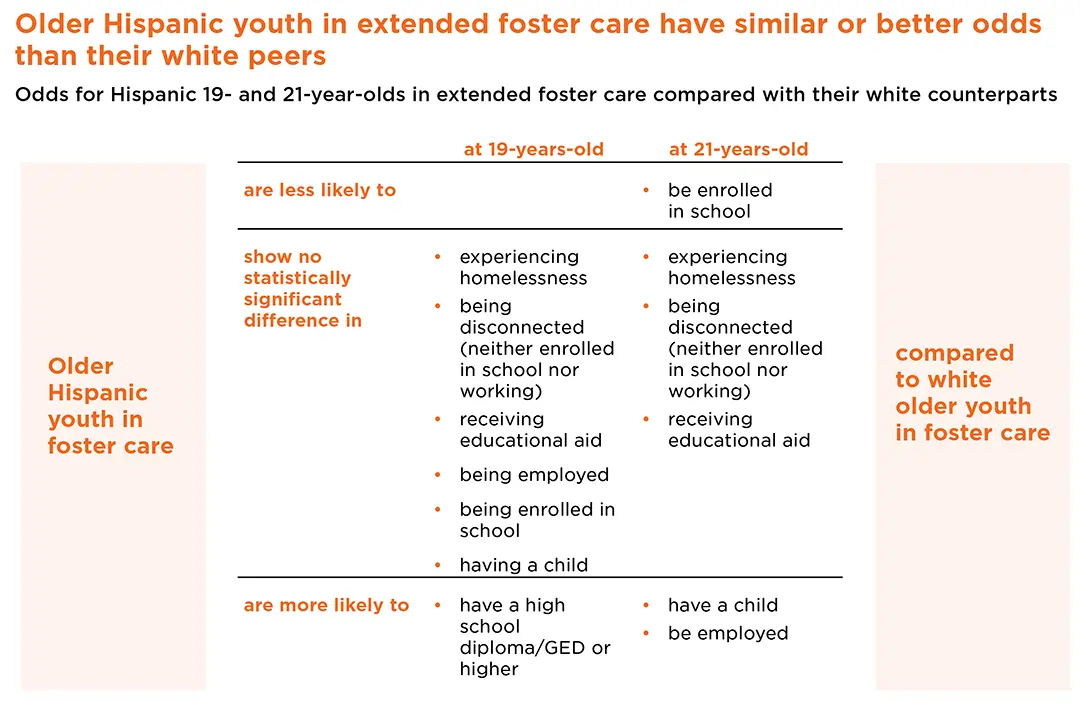

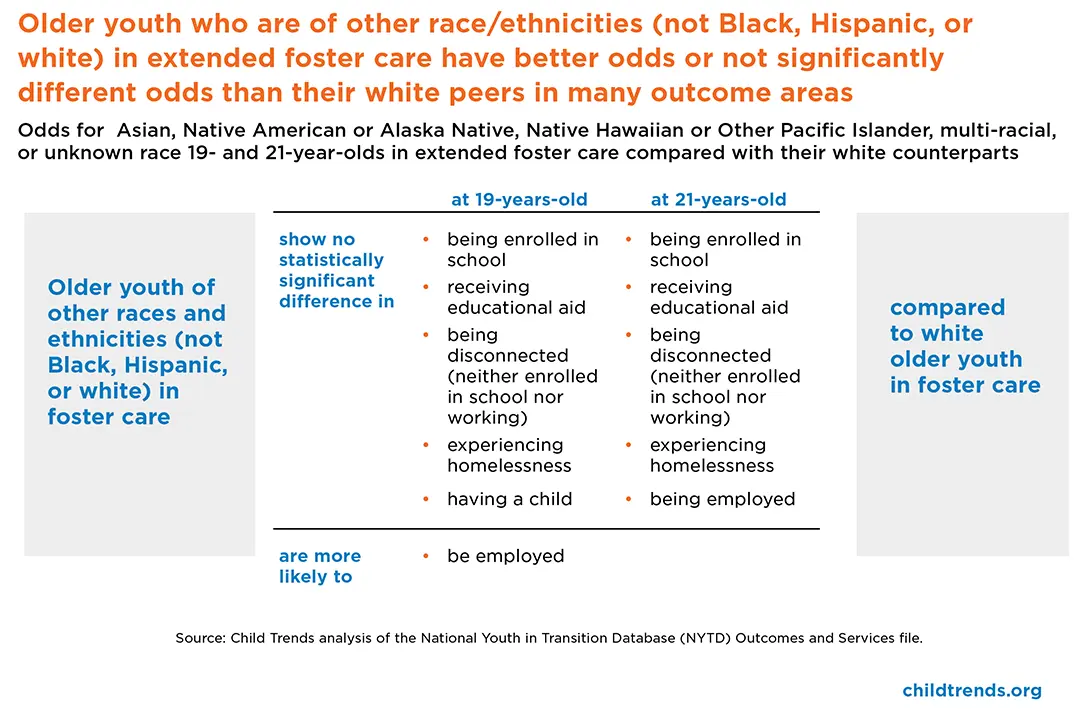

Extended foster care should benefit all older youth, regardless of their race/ethnicity. To examine whether the benefits vary by race/ethnicity, we used the same models described in the previous section and added a moderation effect by race/ethnicity. In many instances, youth of color in extended care experience similar outcomes to their white peers. Older youth who were Asian, Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, multi-racial, or whose race is unknown experienced the same or better odds of positive outcomes than their white peers in almost all outcome areas. When compared to their white peers, black/African American youth experienced more disparities than Hispanic youth. The following are some specific findings from our analysis:

These findings suggest that extended foster care is associated with a decrease in racial and ethnic disparities in some young adult outcome areas.

Discussion of Findings

Based on our findings about the experiences and outcomes of older youth in foster care, we offer several recommendations to ensure that the foster care system is responsive to the unique needs of these young people as they transition to adulthood.

Services and supports must be responsive to the unique ways older youth enter, experience, and exit the foster care system.

The supports and services that older youth and their families receive to prevent foster care placement, as well as those they receive once a youth enters care, need to be developmentally appropriate. Older youth are in a critical developmental stage. As they transition to adulthood, they are learning coping and decision-making skills, developing impulse control, and seeking more independence. This is a process that begins in adolescence and continues well into a young person’s twenties.[12] However, developmentally appropriate behaviors (such as pushing boundaries) may manifest in challenging ways. Older youth are significantly more likely to enter the foster care system due to a behavioral challenge than their peers under the age of 14. Renewed emphasis on prevention services and supports, as exemplified in the Families First Act, may help child welfare agencies and families find alternatives to care that keep young people at home. Additionally, older youth in care often experience more placement instability and a higher likelihood of congregate care placement due to their behaviors.[13] Placement instability and congregate care placements are associated with an increased risk of further system involvement and other negative outcomes, such as delinquency.[14] One strategy for supporting placement stability includes formalizing the relationship between the child welfare and behavioral health systems, which may be better attuned to the developmental changes unique to this population.[15]

Youth who enter care after their 14th birthday are more likely to age out of care without a stable, permanent family. Older youth experience longer stays in foster care and may need tailored supports and services in order to achieve permanency. Specialized programs that work to secure adoptive families and guardianship arrangements for older youth have been shown to be effective.[16] However, these specialized services are not available to all youth in foster care. Additionally, consciously designed teaming practices that work in tandem with the unique strengths of older youth and their families to support permanency and adult connections are emerging as an important addition to the typical skill-based services (i.e., financial management, health living education) many agencies provide.[17]

Additional targeted research could identify next steps to assist older youth during the transition to adulthood

The body of research on the effects of extended foster care is growing. Recent findings show that older youth in extended foster care experience better outcomes than older youth who leave care at 18.[18] Additionally, research demonstrates that the positive effects of extended foster care increase with each year an older youth spends in care.[19] However, more research is needed in several areas:

- Research on subgroups in extended foster care, such as young parents, could help identify services and supports that either hinder or encourage participation. Additional research may illuminate system-level changes that can increase utilization of extended foster care. A better understanding of subgroups in extended foster care may also inform needed adjustments to extended care policies and services for older youth. For example, research could consider differences in extended care eligibility requirements across states and whether such differences affect older youth’s outcomes: It is important to understand if older youth in states with the broadest eligibility requirements have access to programs that are more conducive to the needs of certain subgroups than states with stricter requirements.

- Research on barriers to utilization of extended foster care may help to address the low utilization rate across the country. Utilization of extended foster care has a national average around 25 percent, indicating that states may need more guidance about how to implement extended foster care.[20] For example, child welfare systems may not be providing adequate information to youth about the option to stay in care and the requirements of extended foster care; with better understanding of this implementation barrier, systems may make adjustments and create better protocols for providing this information to older youth.

- Research on older youth who do not stay in extended foster care but continue to receive services is needed to better understand alternative options to extended foster care. Older youth who were receiving services at 18 continued to receive services, regardless of their participation in extended foster care; this indicates that there may be differences between youth who stay in care past age 18 and receive services, and those who leave at age 18 and continue to receive services. Understanding those differences and creating tailored supports for both groups will help ensure that all youth are connected to the level of services and supports necessary for their transition to adulthood.

To support racial and ethnic equity in the child welfare system, use extended foster care as a policy lever to improve outcomes for all older youth in care

Both past research and findings presented here suggest that extended foster care may be associated with a decrease in racial and ethnic disparities in some young adult outcome areas.[21] To achieve equitable results in all outcome areas, however, child welfare agencies must ensure that young people and families of color are receiving tailored services and supports throughout their time in foster care—from initial contact through emancipation. This will require acknowledging and making a commitment to address the existence of structural and systemic racism in the child welfare system. Although extended foster care may help to decrease disparities in young adult outcomes, additional research is needed to better understand the unique experiences of older youth and families of color that are involved in the child welfare system.

Collect high-quality, comprehensive data

To yield useful results, future research efforts will require improvements in the quality and comprehensiveness of data collected on older youth with experience in foster care. While the National Youth in Transition Database is a valuable source of information, changes to the format and collection of these data are needed. Because response rates for NYTD are low across the country (ranging from 20 to 100 percent at baseline data collection),[22] the sample of older youth drawn from NYTD may not be generalizable to the broader population of older youth ages 17, 19, and 21 with foster care experience. Additionally, NYTD should be restructured to allow for collection of more nuanced data; to fully understand this group of older youth, we need more details on their experiences in care.

AFCARS data should also be improved and expanded to better capture the unique characteristics of older youth. For example, more indicators should be added to gather information about young parents who are in foster care. With the 2016 AFCARS Final Rule, some indicators for this subgroup were amended or added starting in the 2020 reporting cycle, but they still do not capture some important information about young parents. This includes information about the children of young parents in care, parents’ access to reproductive medical care, and their access to critical documents such as a driver license and social security card.

Currently, there are no federal reporting requirements for older youth over the age of 18 who are still in foster care. As a result, reporting techniques and quality of reporting on extended foster care varies greatly by state. Additionally, states with state-funded extended care often do not report on young people in extended foster care. Efforts to improve the collection of comprehensive data on this population should focus on both federal Title IV-E extended foster care and state-funded extended foster care reporting requirements.

Conclusions

Older youth who enter foster care differ from children who enter care before the age of 14, in ways that relate to both their phase of development and their experiences in the system (e.g., spending more time in care). To help ensure that older youth can make a successful transition to adulthood, many states have extended foster care beyond age 18, providing additional years of services and supports. Older youth who are in extended foster care, even for a short time, experience better outcomes than their peers not in extended foster care. Extended foster care cannot replace a legal permanent family, but it has emerged as a valuable tool in supporting the success of older youth who do not achieve permanency as they transition to adulthood.

End Notes

[a] Foster care previously ended at age 18; young people in foster care were discharged at age 18 regardless of their individual circumstances.

[b] At the time of this report, The Family First Prevention Services Act had extended the eligibility age to receive services to age 23. However, at the time of publication, data on this change was not available.

[c] At the time of this analysis, information on 21-year-olds in Cohort Two had not been publicly released and is not presented in this brief.

[d] Youth who remained in care for a short period following their 18th birthday were not considered to be in extended foster care due to data quality and privacy considerations built into AFCARS.

[e] Adoption occurs when an adult legally takes responsibility for raising and providing for the youth, and can only occur once parental rights have been terminated. Guardianship occurs when an adult assumes legal guardianship of a child in foster care. Guardianship does not require that parental rights be terminated and is often used as an option when a youth is placed with another family member.

[f] Access to services refers to federally funded Chafee services that are meant to help prepare older youth for adulthood by providing needed information and skill development training that they may not otherwise receive.

[g] FY 2017

[h] Some older youth included in the comparison group (not in extended foster care), may be ineligible for extended foster care due to achieving permanency between ages 17 and 18.

[1] Based on Child Trends Analysis of the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data.

[2] Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73.

[3] Lee, C., & Berrick, J. D. (2014). Experiences of youth who transition to adulthood out of care: Developing a theoretical framework. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 78–84. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.005.

[4] Bender, K., Yang, J., Ferguson, K., & Thompson, S. (2015). Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 222–231. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.06.007.

[5] Berzin, S. C., Rhodes, A. M., & Curtis, M. A. (2011). Housing experiences of former foster youth: How do they fare in comparison to other youth? Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2119–2126. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.018.

[6] Courtney, M. E., Dworsky, A., Lee, J., & Raap, M. (2010). Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at age 23 and 24. Chicago: Chapin Hall at The University of Chicago.

[7] Braciszewski, J. M., & Stout, R. L. (2012). Substance use among current and former foster youth: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2337–2344. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.011

[8] Courtney, M. E., Dworsky, A., Lee, J., & Raap, M. (2010). Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at age 23 and 24. Chicago: Chapin Hall at The University of Chicago.

[9] Juvenile Law Center (2018). Extended foster care. Retrieved from: https://jlc.org/issues/extended-foster-care

[10] Ringeisen, H, Tueller, S., Testa, M., Dolan, M., & Smith, K. (2013). Risk of long-term foster care placement among children involved with the child welfare system. OPRE Report #2013-30. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[11] Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018). Fostering youth transitions: using data to drive policy and practice decisions. Retrieved from: https://www.aecf.org/resources/fostering-youth-transitions.

[12] Annie E. Casey Foundation (2011). The Adolescent Brain: New Research and Its Implications for Young People Transitioning from Foster Care, Executive Summary. Retrieved from: https://jbcc.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/jcyoi_adolescent_brain_

development_executive_summary_final_090611.pdf

[13] Children’s Bureau (2015). A national look at the use of congregate care in child welfare. Retrieved from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cbcongregatecare_brief.pdf

[14] Ryan, J. P., Marshall, J. M., Herz, D., & Hernandez, P. M. (2008). Juvenile delinquency in child welfare: Investigating group home effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(9), 1088-1099.

[15] Wells, R., & Chuang, E. (2012). Does formal integration between child welfare and behavioral health agencies result in improved placement stability for adolescents engaged with both systems?. Child welfare, 91(1), 79.

[16] Vandivere, S., Malm, K., Zinn, A, Allen, T., & McKlindon, A, (2015). Experimental evaluation of a child-focused adoption recruitment program for children and youth in foster care. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(2), 174-194.

[17] Rauktis, M. E., Kerman, B., & Phillips, C. M. (2013). Transitioning into adulthood: Promoting youth engagement, empowerment, and interdependence through teaming practices. In Contemporary issues in child welfare practice(pp. 101-125). Springer, New York, NY.

[18] Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., Park, K., Harty, J., Feng, H., Torres-Garcia, A., & Sayed, S. (2018). Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of youth at age 21. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

[19] Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., & Park, S. (2018). Report from CalYOUTH: Findings on the relationship between extended foster care and youth’s outcomes at age 21. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

[20] Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018). Fostering youth transitions: using data to drive policy and practice decisions. Retrieved from: https://www.aecf.org/resources/fostering-youth-transitions/

[21] Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., & Park, S. (2018). Report from CalYOUTH: Findings on the relationship between extended foster care and youth’s outcomes at age 21. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

[22] National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (2016). National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) Outcomes file users guide: Cohort 1. Retrieved from: https://www.ndacan.cornell.edu/datasets/pdfs_user_guides/Dataset202UsersGuide.pdf

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube