Rural and Urban Women Have Differing Sexual and Reproductive Health Experiences

Even though all rural communities are distinct, many feature well-documented social and structural barriers for women to access sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care. Compared to urban areas, rural communities are less likely to have sufficient SRH providers and medical facilities. Rural family planning clinics are more likely be understaffed and under-resourced, and rural clinicians have lower levels of training—specifically in contraceptive provision—than their counterparts in urban areas. Rural patients also face low appointment availability, long travel times, and other logistical challenges, and privacy and confidentiality concerns. Furthermore, cost, lack of health insurance, and poverty are frequently noted barriers to accessing care for rural patients. Rural residents of color and immigrants in rural areas are disproportionately impacted by these barriers.

Barriers to care contribute to noted disparities in SRH outcomes between rural and urban women, including higher rates of unintended pregnancy, poorer infant and maternal outcomes, and lower rates of pap tests in rural areas. Rural women of color often experience disproportionately worse outcomes. There is limited recent data on differences in contraceptive method between rural and urban women, although an older analysis of national data (2011–2015) found that a higher proportion of sexually active rural women used a highly effective method (IUD/implant or sterilization) than urban women.

For this brief, we sought to understand whether barriers to care impact receipt of SRH services and contraceptive method use among women in rural communities. We used NSFG data from 2015-2019 to analyze the differences between sexually active rural and urban women not seeking pregnancy, first in terms of sociodemographics and then in terms of SRH indicators. This brief is intended to provide Title X providers and SRH advocates with context regarding the care-seeking patterns and SRH needs of their rural patients.

Key Findings

- Compared to urban women, a higher proportion of rural women are non-Hispanic White, born in the United States, have a household income below the federal poverty level[1], identify as straight, have already had at least one birth, and do not intend to have future births.

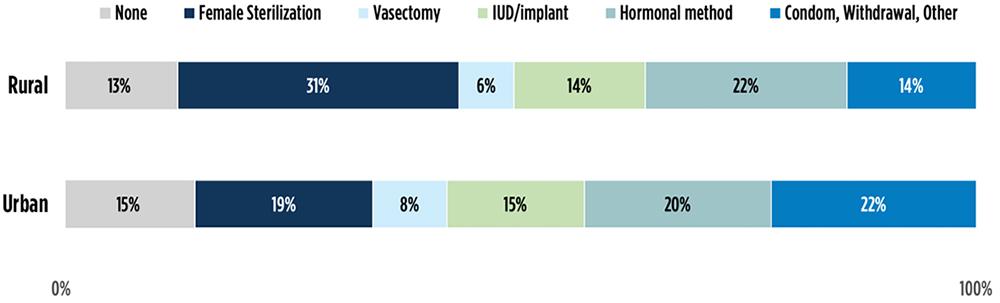

- A higher proportion of rural women rely on female sterilization[2] (31%) to prevent pregnancy than urban women (19%), and a lower proportion rely on condoms, withdrawal, and other non-prescription methods (14%) than among urban women (22%).

- The proportions of rural and urban women receiving SRH services in the past year were not significantly different (72% and 76%, respectively). However, a higher proportion of rural women received care at federally-funded, Title X facilities (11%) than urban women (7%).

Methodology and Data

We pooled data from 2015-2017 and 2017-2019 female respondent files[3] of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)—a nationally representative survey of people ages 15 to 49. We limited our analyses to respondents who reported having a male sexual partner in the past 12 months. Additionally, we excluded those who were pregnant, postpartum, seeking pregnancy, or sterile (however, we did include respondents who had undergone a sterilization procedure for contraceptive purposes). Respondents living outside of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) were considered rural residents (N = 1,128), while respondents residing within an MSA (including the principal city of an MSA or other MSA) were categorized as urban (N = 6,007).

We ran weighted tabulations and conducted Pearson’s Chi-Square tests to compare sociodemographic characteristics, current contraceptive method use, and receipt of SRH care[4] in the last 12 months among all sexually active rural and urban respondents. Next, we ran the same tabulations limited to those women not relying on female sterilization as their most effective method of contraception. Finally, we ran multivariate logistic regressions using residence as the key independent variable to assess whether differences in use of female sterilization between rural and urban residents could be explained by sociodemographic characteristics (specifically age, race/ethnicity, income, whether the respondent had a birth, relationship status, health insurance, education, and employment status). Reported differences are significant at p<.05 unless otherwise noted.

Findings

Sociodemographic characteristics

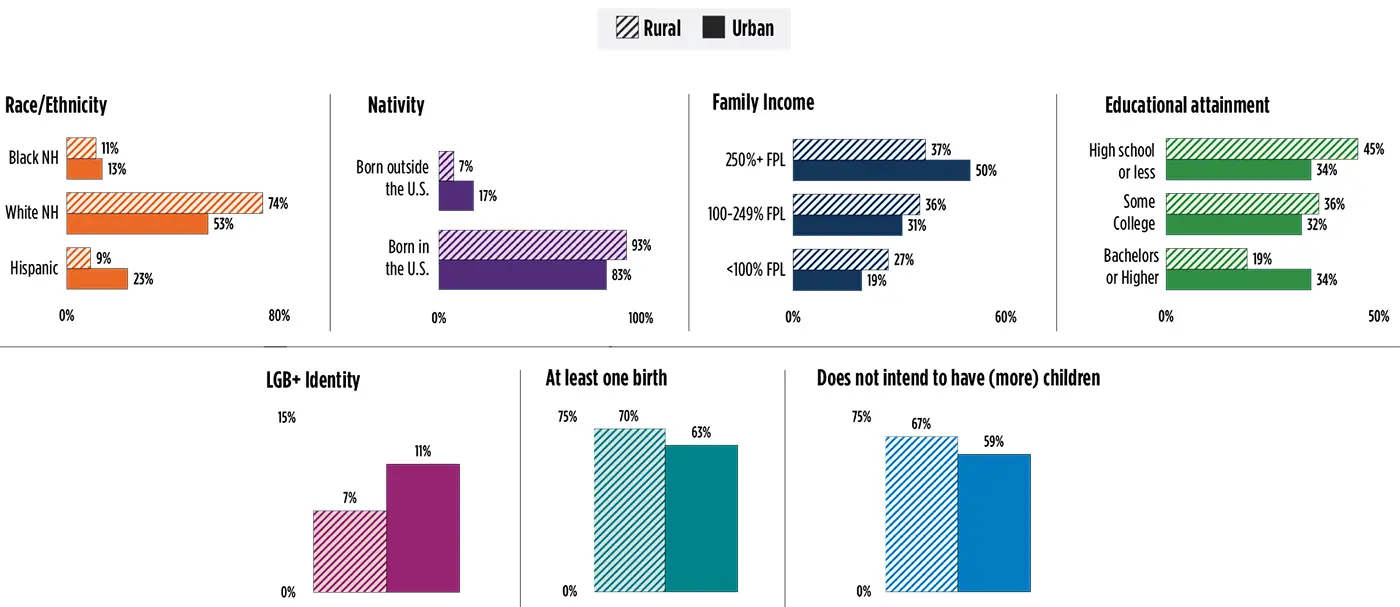

Rural and urban women who are sexually active and not seeking pregnancy are similar in terms of their age, marital status, employment status, and health insurance coverage. However, the two groups of women differ across other sociodemographic characteristics highlighted in Figure 1.

- A higher proportion of rural women are non-Hispanic White (74% vs 53%) and a lower proportion are Hispanic (9% vs 23%), compared to urban women. Additionally, the proportion of rural women born outside of the United States (7%) is less than half that of urban women (17%).

- Rural women have lower incomes than urban women, with 27 percent of rural women living below the federal poverty level, compared to 19 percent of urban women.

- Rural women were also less likely to have completed a bachelor’s degree or further graduate study than urban women (19% vs 34%).

- A lower proportion of rural women identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or “something else” (LGB+) than urban women (7% vs 11%).

- A higher proportion of rural women report having had least one birth (70% vs 63%) and a higher proportion do not intend to have a future birth (67% vs 59%), compared to urban women.

Figure 1. Demographic Differences Between Sexually Active Rural and Urban Women, 2015-2019

Related Content

- Title X Provider Strategies to Increase Client Access to Family Planning Services

- Promising Practices for Expanding Students’ Awareness and Use of School-based Family Planning Services

- Offering Sexual and Reproductive Health Services to Adolescents in School Settings Can Create More Equitable Access

Contraceptive use

Differences in contraceptive methods used

Patterns in current contraceptive method use were different between rural and urban women (Figure 2). A much higher proportion of rural women rely on female sterilization (31%) than their urban counterparts (19%), and a lower proportion rely on condoms, withdrawal, and other non-prescription methods (14%) relative to urban women (22%). When women relying on female sterilization are excluded from the analysis, a higher proportion of rural women rely on short-term hormonal methods[5] (32% vs 25%) and a lower proportion rely on condoms, withdrawal, and other non-prescription methods[6] (20% vs 28%) compared to urban women (not shown in a figure).

Figure 2. Current Contraceptive Method Use Among Rural and Urban Women, 2015-2019

Demographic differences in sterilization use

Even when controlling for demographic characteristics associated with sterilization in multivariate models, rural women were still more likely to rely on female sterilization than urban women. Additionally, older women, women with incomes below the federal poverty level, women who had at least one child, and women with a high school degree or less were more likely to rely on sterilization.

Receipt of SRH care

Among rural women, 72 percent received any SRH care in the past 12 months, compared to 76 percent of urban women; however, this difference was not statistically significant.[7] The majority of both rural and urban women receiving services obtained care at a private doctor (83% rural, 82% urban), but a higher proportion of rural women (11%) received services at a federally funded Title X clinic than urban women (7%).

Discussion of Findings

This analysis uses the latest NSFG data to provide updated comparisons of sexually active rural and urban women’s sociodemographic characteristics and contraceptive method use, and to compare recent receipt of SRH care between rural and urban women.

Similar to previous studies, we found that rural women were more likely to identify as White, to be living under the federal poverty level, and to have lower levels of education than urban women. Given that women living in poverty are less likely to receive family planning care and to report lower quality of care experiences than their counterparts, our finding that rural women experience higher rates of poverty may be salient to SRH providers who are interested in understanding the lived experiences of their patients (and potential patients). Interestingly, despite evidence of barriers to accessing SRH services in other studies, we found that rural women were about as likely to have received care in the past 12 months as their urban peers. Additionally, rural women were more likely than urban women to have visited a Title X clinic for services (although the majority of women in both settings visited a private doctor), indicating that they have access to providers that offer the full range of contraceptive methods and a wide range of services for free or at low cost. However, ability to access to care does not necessarily mean that services were easy to access. The long distances and lack of available services in rural settings (documented in other research) may make it more difficult for women to receive the full range of SRH services they seek.

Ease of access to care may also impact the types of contraception family planning clients can choose. We found that rural women are more likely to rely on sterilization than urban women. This is in line with research from the 2006-10 and 2013-17 NSFG, which shows that the gaps in contraceptive method choice between urban and rural residents have in fact widened as urban women have decreased their use of sterilization. In multivariate analyses that controlled for demographic factors associated with sterilization, rural residency was still significantly associated with an increased likelihood of relying on sterilization. While sterilization may be a real preference for many who choose to get the procedure, it is possible that lack of easy access to care has led more rural women to select sterilization (a permanent method that requires no follow-up contraceptive appointments once complete) or that rural providers are encouraging sterilization knowing that long-acting methods are often less available in rural areas. Future research should consider potential drivers of the differences in the use of sterilization and whether rural women are able to access their preferred contraceptive methods.

Limitations

This analysis uses cross-sectional data, which did not allow us to assess when women began using their current contraceptive method relative to their most recent SRH service visit. Additionally, the small number of rural women in the NSFG sample meant that we had to pool across five years of data, covering a timeframe during which the funding and policy landscape around SRH care was rapidly shifting. Despite these limitations, our analysis provides updated data on the demographics, contraceptive method choices, and SRH service receipt of urban and rural women potentially seeking to access care.

Footnotes

[1] $27,750 for a family of four in 2022, per the following guidelines: https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines

[2] Tubal ligation (or having one’s “tubes tied”), and Essure®.

[3] The NSFG does not ask respondents about their gender identity. While we refer to those in the female respondent file as women in this brief, it is important to note that transgender and gender non-conforming people may be included in our sample. Additionally, individuals of all gender identities seek SRH services.

[4] Sexual and reproductive health care includes a birth control method, birth control counselling, tests or checkups related to birth control, STI testing or treatments, pregnancy tests, pap smears, and pelvic exams.

[5] Short-term hormonal methods include Depo Provera, pills, the patch, and the ring.

[6] Nonprescription methods include diaphragms, spermicides, and natural family planning such as the calendar or rhythm method, basal body temperature, and cervical mucus tests.

[7] This difference was marginally statistically significant (p = 0.051).

Acknowledgments

Suggested citation

Pliskin, E., Welti, K., & Manlove, J. (2022). Rural and urban women have differing sexual and reproductive health experiences. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/6910b2254v

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram