Lessons From a Historic Decline in Child Poverty

Chapter 1. Introduction

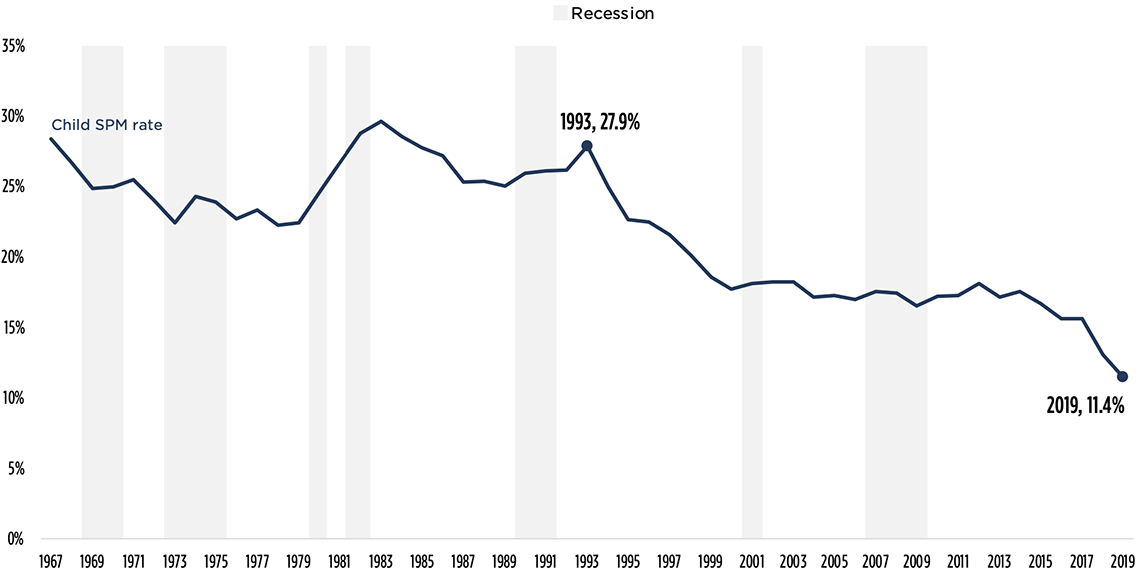

The past quarter century witnessed an unprecedented decline in child poverty rates. In 1993, the initial year of this decline, more than one in four children in the United States lived in families whose economic resources—including household income and government benefits—were below the federal government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) threshold. Twenty-six years later, roughly one in 10 children lived in families whose economic resources were below the threshold. This is an astounding decline in the child poverty rate, which has seen child poverty reduced by more than half (59%; see Figure 1.1). The magnitude of this decline in child poverty is unequaled in the history of poverty measurement in the United States.

What led to this remarkable decline in child poverty? And did all subgroups of children experience similar declines? We set out to answer these questions, to understand the constellation of influences that led to this decline, with the hope that what we learned will help policymakers sustain—and accelerate—progress.

Figure 1.1. Child Poverty Rates Measured Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), 1967-2019

Note: To provide context for the more recent decline in child poverty, we present trends in child SPM poverty rates back to 1967.

Sources: Child Trends’ analysis of the historical Supplemental Poverty Measure data from the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy, anchored to 2012 thresholds. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Building on previous research

Often, when researchers talk about poverty in the United States, we refer to a specific point in time, or we compare the current year’s poverty rate to the rates for the last couple of years. Similarly, when researchers examine policy levers for reducing child poverty or improving child outcomes, we tend to look at one policy change or one program at a time. In this report, though, we’ve taken a big step back, similar to a 2016 report published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that examined 50 years of poverty trends. We look specifically at how the landscape of child poverty has changed over the past quarter century.

For us, this report has been an exercise in listening to history, analyzing 40 years of data, reading the technical appendices of the National Academy of Sciences’ A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, and drawing on and expanding existing research. Our work builds explicitly upon prior research—conducted by Hilary Hoynes (University of California, Berkeley), Marianne Page (University of California, Davis), and Ann Huff Stevens (University of Texas at Austin). We owe them a debt of gratitude for their contribution to our understanding of how competing economic and labor market trends influenced poverty rates through the early 2000s. We’ve updated their work to include an additional 15 years of data, from 2004 to 2019. We’ve also extended their work to look, specifically, at the influence of federal anti-poverty programs on poverty rates through our use of the SPM, which includes the cash value of government benefits in its measure of family resources. (The SPM had not yet been developed when Hoynes, Page, and Stevens’ report was released in 2006.) Finally, while their work focused on poverty rates more generally, our analyses focus exclusively on child poverty in the United States. And by looking across economic, demographic, and policy factors, our findings speak to policy levers intended not just for reducing child poverty and mitigating its impact on child development, but also for addressing some of the root causes of poverty among families with children.

Our work has also benefitted from the insights of researchers who have focused on examining and remedying poverty among specific groups of children at elevated risk of poverty—notably Dolores Acevedo-Garcia (Brandeis University) and Regina Baker (University of Pennsylvania). Their work shows how the likelihood that a child will experience poverty is shaped by structural forces often beyond their family’s control. We explore some of these forces by examining child poverty among subgroups of children, based on their family’s immigration status, their race/ethnicity, their family structure, and the stability of their parent(s)’ employment. The idea that poverty is heavily shaped by structural forces can, on first consideration, seem daunting, but it gives us hope that structural changes can lead to widespread reduction in the prevalence of child poverty.

Finally, this work would not have been possible without data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC), collected by the Census Bureau, and the Bureau’s development of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). Similarly indispensable was the historical, anchored SPM developed by and made public by the Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy. Our work also builds on the extensive body of research conducted by Jane Waldfogel, Chris Wimer, and the Columbia team, which has used the anchored SPM to examine trends in child poverty over time.

Any missteps we’ve made in our interpretation of our colleagues’ work or our attempt to build on it are solely our responsibility.

Research questions

We began our work eager to understand the influences that led to child poverty’s decline over the last quarter century. Numerous economic, demographic, and public policy shifts have occurred over this time. On the economic front, we’ve seen real (inflation-adjusted) growth in gross domestic product (or GDP) per capita, median household income, and state minimum wages. Single mothers’ labor force participation grew, particularly in the mid-to-late 1990s. And unemployment was lower in 2019 than in 1993. On the demographic front, the share of adults with at least a high school degree and the share of kids living in two-parent families (including cohabiting parents) grew, albeit only slightly for the latter. The shares of children who are Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, or living in immigrant families grew. Teen birth rates declined dramatically. On the policy front, we’ve seen a large increase in overall federal spending on social safety net programs, particularly refundable tax credits aimed primarily at working families with children. At the same time, we’ve seen a move away from out-of-work cash assistance and the introduction of new immigrant exclusion policies.

So, what led to this historic decline in child poverty? Using fixed effects regression models and descriptive counterfactual analyses, we set out to answer the following questions:

1. What led to this historic decline in child poverty?

-

- What roles have economic, labor market, and demographic factors played in explaining the declining poverty rate among children?

- Has the social safety net improved over time at protecting children from poverty?

2. Did all groups of children experience a similar decline?

3. For which children has the social safety net worked and who has it left behind?

Our approach

Before diving into the study, we offer thoughts about our approach, specifically around the time frame of our analysis, the levels of poverty that we examined, the ways in which we present our findings (percentage points versus percent), and our methodology.

The analysis time frame

We chose 1993 as our starting point for three interrelated reasons.

First and foremost, 1993 is the year in which child poverty began its unprecedented decline.

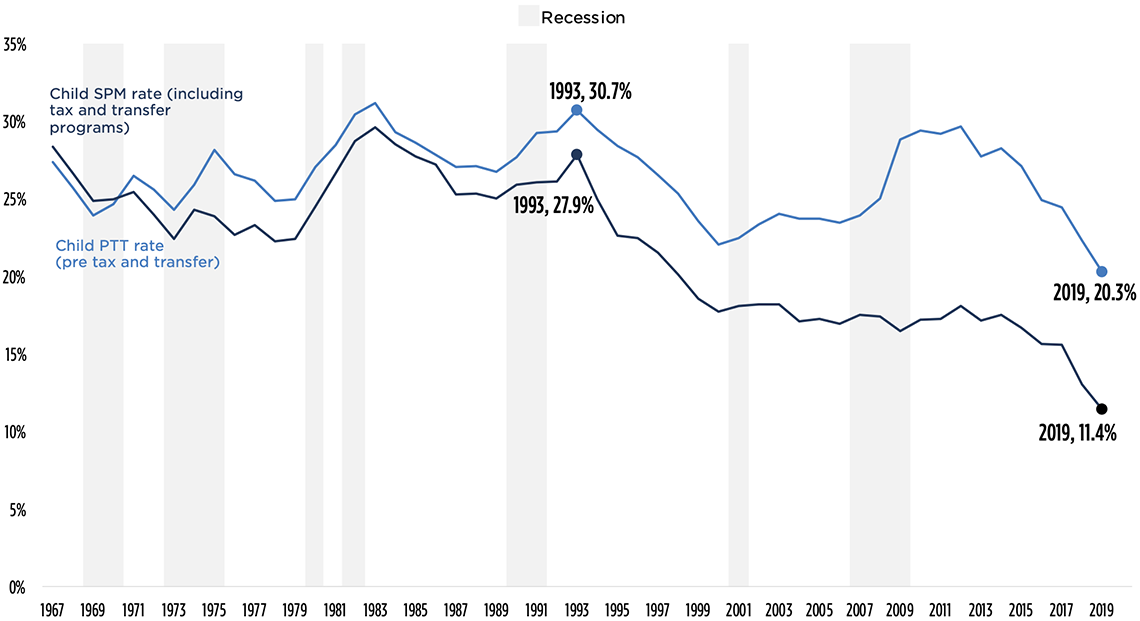

Second, around this time, child poverty trends began to follow a very different pattern. Prior to 1993, child SPM poverty rates (as represented by the dark blue line in Figure 1.2, below) rose and fell in sync with economic cycles (shown by the presence and absence of recessions, represented by the light gray columns in Figure 1.2). Pre-tax-and-transfer (PTT) child poverty rates—poverty rates based solely on income, and that do not include benefits from government tax and transfer programs—are shown with the light blue line. PTT poverty rates also followed economic cycles before 1993, and have continued this pattern to the present. In 1993, however, the trends in SPM child poverty started to diverge from this pattern—declining more steeply during economic booms and leveling off during economic downturns—suggesting that other factors are at play.

Third, the anti-poverty policy landscape began to shift in the early 1990s, primarily due to increased federal spending on the social safety net, accompanied by a shift away from out-of-work cash assistance at both the state and the federal levels and the introduction of new immigrant exclusion policies. While no single point in time can capture the multifaceted nature of this shifting policy landscape, beginning in 1993 allows us to capture a time period that includes these changes.

Figure 1.2. Child Poverty Rates Measured Two Ways: Accounting for Federal Tax and Transfer Programs (the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM) and Without Them (Pre-Tax-and-Transfer, or PTT), 1967-2019

Note: To provide context for the more recent decline in child poverty, we present trends in child SPM poverty rates back to 1967.

Sources: Child Trends’ analysis of the historical Supplemental Poverty Measure data from the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy, anchored to 2012 thresholds. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

But why end in 2019?

We chose to exclude 2020 from our analyses because it was an anomalous year with respect to both economic conditions and the enactment of temporary policies that addressed the dual public health and economic crises. Our goal is to examine the more permanent, underlying factors that influence child poverty in the United States, and we concluded that 2020 would muddy rather than clarify our analyses.

We considered one more question about our time frame: Was it problematic to start with the post-recession recovery of 1993 and conclude with the economic trough of 2019? We decided it was not: Our fundamental question is to ask what contributed to the decline in child poverty from 1993 to 2019. Part of the answer may very well be (indeed, is likely to be) that there was a tighter labor market in 2019 than in 1993. How much of the decline is due to this tighter labor market and how much is due to other factors is part of what we explored.

While our focus in this report is from 1993 to 2019, our graphs provide, when available, data for previous years as context.

Levels of poverty

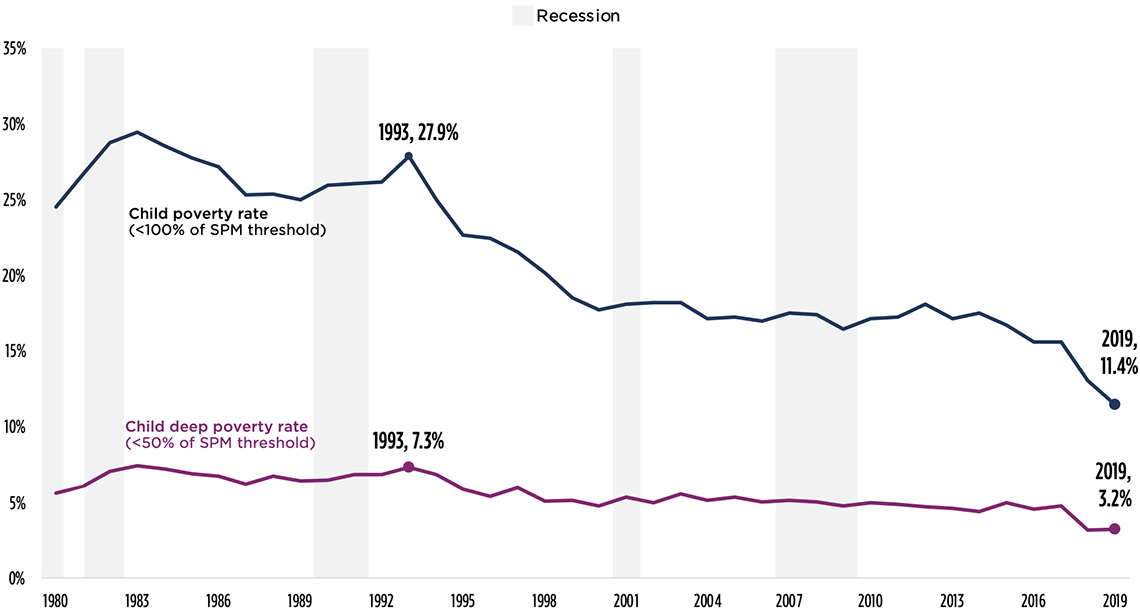

While we opened this report by highlighting the decline in child poverty, we present, throughout this work, parallel analyses for rates of children in poverty and in deep poverty. In 2019, families with a household income of less than approximately $28,881 (for a two-adult, two-child household that rents) were considered to be experiencing poverty. Families experiencing deep poverty are defined as having household net resources below 50 percent of the SPM poverty threshold. In 2019, families with a household income of less than approximately $14,440 (for a two-adult, two-child household that rents) were considered to be experiencing deep poverty.

Rates of deep poverty among children experienced a similar decline to the rates of those in poverty. In 1993, approximately 7 percent of children lived in families whose incomes were below the deep poverty threshold (see Figure 1.3). By 2019, the rate of children in deep poverty had declined to 3 percent. This represents a decline of 56 percent, just slightly smaller than that seen for child poverty rates. However, much of this decline occurred from 1993 to 1996, and again from 2017 to 2019.

Figure 1.3. Child Poverty and Deep Poverty Rates Measured Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), 1980-2019

Sources: Child Trends’ analysis of the historical Supplemental Poverty Measure data from the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy, anchored to 2012 thresholds. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In the chapters that follow, we look at the roles of economic, demographic, and policy factors in shaping the landscape of deep poverty as well as that of poverty.

A note about percentage point vs. percent change, and the need to use both

We use both absolute and relative measures to present estimates of the extent to which economic, demographic, and policy factors influenced child poverty.

Absolute measures—specifically, for our purposes, percentage point decreases (or increases) in the number of children protected from poverty—are helpful to concretize the extent to which a social safety net program, for example, reduces poverty. The drawback, however, is that absolute values are difficult to compare across time periods or subgroups that have different baseline poverty rates. For example, absolute measures will be smaller in 2019 than in 1993 because poverty rates were much lower in 2019. Similarly, absolute measures are hard to compare across different levels of poverty: For example, a 1 percentage point reduction in deep poverty represents more than a 30 percent reduction in the deep poverty rate of 3 percent, while a 1 percentage point reduction in poverty represents about a 9 percent reduction in the poverty rate of 11 percent.

Relative measures—such as percent decreases in poverty rates—account for baseline poverty rates and are therefore particularly useful when comparing estimates across time, groups, or levels of poverty. The drawback here, however, is that they highlight the proportional difference in poverty over time, by group, or due to a specific factor. For example, the proportional role of the social safety net in reducing child poverty (as represented by its percent decrease) can increase over time even while the absolute number of children protected from poverty decreases. This can happen when child poverty rates are decreasing over time: The number of children served by the safety net can decrease because the number of children who are eligible for these programs has declined; meanwhile, if—at the same time—benefits are becoming more generous or eligibility criteria have changed such that programs are serving a greater percent of children in poverty, the role of the safety net (proportional to the number of children in poverty) can increase.

Together, these measures produce a more complete understanding of how the landscape of child poverty has shifted over time and allow us to compare the influence of economic, demographic, and policy factors over time and across levels of poverty and groups of children.

Our methodology (Chapter 7)

We use two different analytic approaches to examine the influence of economic and demographic shifts (Chapter 2) and social safety net programs (Chapters 3 and 4) on child poverty.

To look at economic and demographic influences, we follow the approach used by economists Hillary Hoynes, Marianne Page, and Ann Huff Stevens. Capitalizing on state-level variation in the timing and degree of changes in each of the factors examined, we use state and year fixed effects regression models to estimate the associations between changes in each economic and demographic factor and changes in child poverty.

Because changes in federal policies often affect all states at the same time, this method does not allow us to evaluate associations between federal policies and child poverty rates. Therefore, we use descriptive analysis to look at the role of the social safety net programs, following the approach used by the United States Census Bureau: We compare actual child poverty rates using the SPM to estimated counterfactual poverty rates if an individual federal tax and transfer program (or the entire social safety net) were removed from the calculation of SPM household resources. Neither of these methods is causal, and neither account for behavioral changes or interactions between factors. These methods are not directly comparable, but we present a rough approximation of how much each factor is contributing to the overall decline in child poverty as a high-level takeaway, complete with caveats.

What’s next

In Chapter 2, we examine the influence of economic and demographic factors on child poverty rates and their role in explaining the decline in child poverty from 1993 to 2019. In Chapter 3, we explore the role of the social safety net in explaining this historic decline. In Chapter 4, we examine whether child poverty rates have similarly declined for all subgroups of children, as well as the extent to which social safety net programs are equally protective of children with different characteristics. A detailed summary of the findings from these chapters can be found in Chapter 5, along with thoughts about directions for future research. Chapter 6 presents key lessons learned and their implications for policymakers. Finally, you can read about our methodology in Chapter 7.

Click to continue to Chapter 2: The Influence of Economic and Demographic Trends on Changes in Child Poverty

View Chapter 2© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube