Evaluating Pulse: Lessons from an online evaluation of an app-based approach to teen pregnancy prevention

Pulse: An app-based teen pregnancy prevention intervention

This brief was updated on June 10, 2019. You can download the original text here.

Since 2016, Child Trends has collaborated with Healthy Teen Network, Ewald & Wasserman Research Consultants, and MetaMedia Training International to evaluate Pulse, an innovative web-based mobile app designed to empower young women to take control of their health by providing on-demand access to comprehensive, medically accurate sexual health information. The Pulse evaluation is funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Health under a grant to rigorously evaluate “new or innovative approaches to prevent teen pregnancy.” Child Trends has completed impact analyses of data from the first cohort of participants (2016–2018) and will publicly release these results in the future. In 2018 and 2019, the study team recruited a second cohort of participants and is currently conducting analyses. The study team will then publicly release the subgroup findings and a report on the evaluation’s implementation.

This resource provides a brief introduction to the Pulse intervention and describes Child Trends’ unique approach to evaluating Pulse’s impact on teen pregnancy. For this intervention, Child Trends recruited a large sample of mostly Black and Latinx young women completely online. The study team was able to retain most of these women for the duration of the intervention and post-test survey administration by using the app in conjunction with pre-programmed, automatically delivered text messages.

The need for technology-based interventions

Rates of unplanned pregnancy are highest among women in their older teens and early twenties,1,2 yet the majority of teen pregnancy prevention programs are designed for younger teens. Only 8 percent of the nearly 500,000 teens served by the Office of Adolescent Health’s national Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program from 2010 to 2014 were age 16 or older.3 And despite recent declines in teen birth rates among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States, Black and Latinx teens continue to experience birth rates more than twice as high as their white peers,2, 4 highlighting the need for program approaches that target racial and ethnic minority populations. To address these gaps, teen pregnancy prevention programs have increasingly incorporated technology-based components, but more conclusive research is needed on the efficacy of these approaches.

The Pulse program

Pulse is a web-based mobile health app designed for Black and Latinx women ages 18–20. Through culturally and age-appropriate content, Pulse provides information on birth control, healthy relationships, sexual health and physiology, pregnancy, and utilization of clinical services to encourage users to choose effective birth control, seek reproductive health services, and ultimately, prevent unplanned pregnancies.

App content

The Pulse intervention app has six interactive sections with information on sexual and reproductive health topics. It contains activities that engage young women with the content, such as videos featuring medical professionals, a clinic locator, and appointment reminders.

Intervention and Comparison App Main Pages and Intervention Content Page

Know Your Body promotes sexual health by explaining basic anatomy and physiology, and telling users how to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Know Your Options supports sexually active women in assessing and selecting the best birth control method for them. It promotes birth control literacy, and includes information about all birth control methods with an emphasis on long-acting reversible contraception.

Get Personal supports women who are considering initiating sexual activity, helps them identify abusive behaviors in their relationships, and demonstrates negotiation of condom use with a partner.

Take Action empowers women to visit a health clinic by guiding them to a local clinic through a clinic finder, and orienting them on expectations in a clinic visit.

Make A Plan orients women who think they may be pregnant, or are pregnant, and who are currently navigating prenatal care services.

Get Savvy answers women’s additional questions in text and video format and directs them to additional web-based resources and hotlines.

Evaluation of Pulse

From 2016 to 2018, Child Trends used a randomized controlled design to evaluate the impact of Pulse on two measures of unprotected sex (sex without any birth control method, and sex without a hormonal/LARC method), as well as the program’s impacts on knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions. The intervention lasted six weeks and consisted of unlimited access to the app and receipt of text messages. The project team administered an online survey at the end of the six-week intervention, and 86 percent of the sample completed it.

Evaluation key features:

- The evaluation was fully technology-based: All recruitment, enrollment, intervention content, and pre- and post-survey participation took place online. Most participants completed all sections on smartphones.

- Participants were recruited through ads on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.*

Example of Pulse ads

- Participants completed a screener; if they met eligibility criteria, they were directed to an online enrollment form, consent form, and baseline survey. Upon completion of the baseline survey, participants were randomized to either the intervention or comparison group.

- Child Trends followed a protocol for identifying and removing scammer and duplicate accounts from the sample to ensure that only eligible individuals were in the study.

- Pulse comparison and intervention apps looked and felt similar aesthetically.

- The project team sent weekly text messages to participants. These messages contained sexual and reproductive health information (for intervention participants) or general health information (for comparison participants) with fun and engaging animations.

Example Text Messages

- The study team sent reminder text messages to participants to encourage them to view the app and/or take the post-test survey (if they had not yet done so).

- The team sent checks or gift card incentives to participants after they completed baseline and follow-up surveys.

* The study team also recruited through ads on Google AdWords and Snapchat but only recruited two participants through these platforms.

Eligibility requirements

At enrollment, participants had to meet the following criteria:

- Self-identify as female

- Ages 18–20

- Not currently pregnant or trying to become pregnant

- Has daily access to a smartphone

- Currently living in the United States or a U.S. territory

- Speaks English

- Black and/or Latinx (Cohort 2 only)

Recruitment

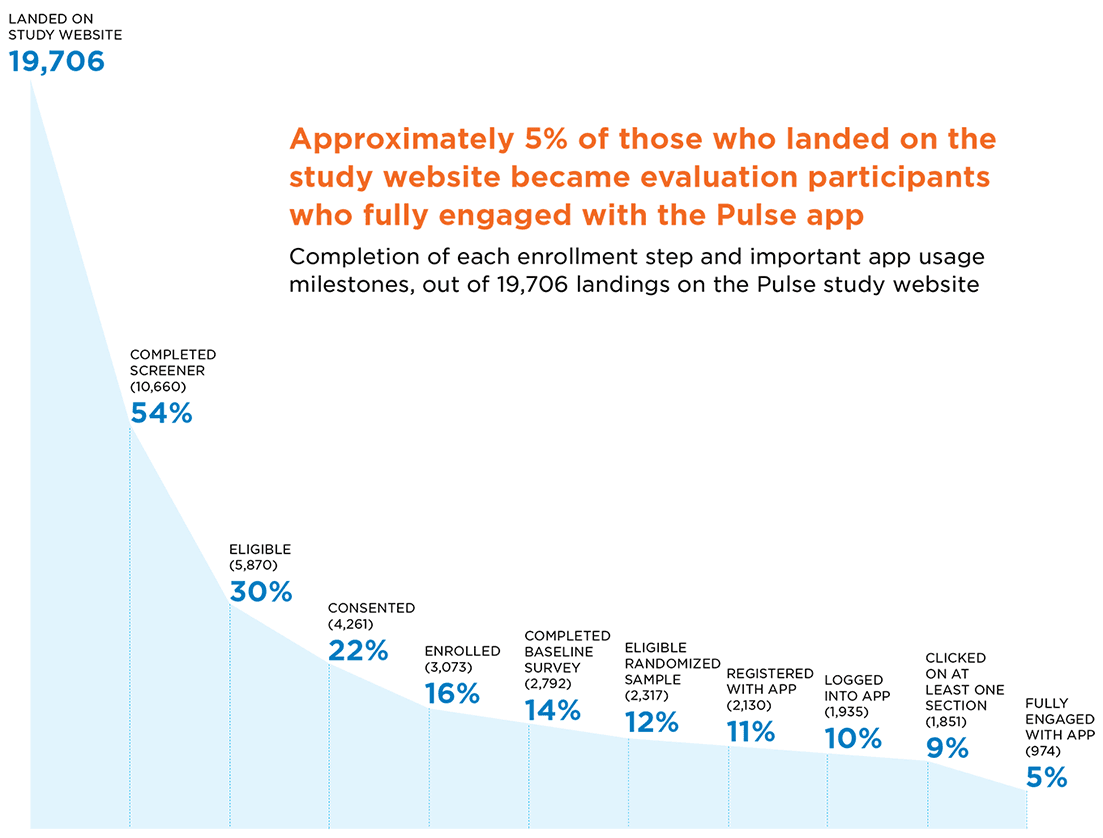

Recruitment through social media ads resulted in 19,706 unique landings on the Pulse study website.* From those unique landings, the screener was completed 10,660 times (representing 54% of all those who landed on the screener page); 4,790 completions did not meet the study eligibility requirements. Of the 5,870 screener responses accounts that were eligible (representing 30% of the original landings), 4,261 (22%) consented to the study, 3,073 (16%) enrolled in the study, and 2,792 (14%) completed the baseline survey and were randomized (1,399 to intervention and 1,393 to comparison). We then removed 475 scammer or duplicate accounts from the randomized sample (233 from the intervention group and 242 from the control group), resulting in a final randomized sample of 2,317 participants in the evaluation study (representing 12% of those who landed on the screener page). From the evaluation sample, 2,130 participants registered with the app (representing 11% of those who landed on the screener page), and 1,935 (10%) logged into the app. Additionally, 1,851 (9%) participants clicked on at least one of the six Pulse sections and 974 (5% of the original sample landing on the screener page) were “fully engaged” with the app, meaning they clicked on at least one activity within each of the six sections.**

* Analytic data for November 2016 through January 2017 are not available and therefore not included in these estimates.

** The study team agreed that this threshold represented the minimum dosage needed to receive the key elements of the program’s content.

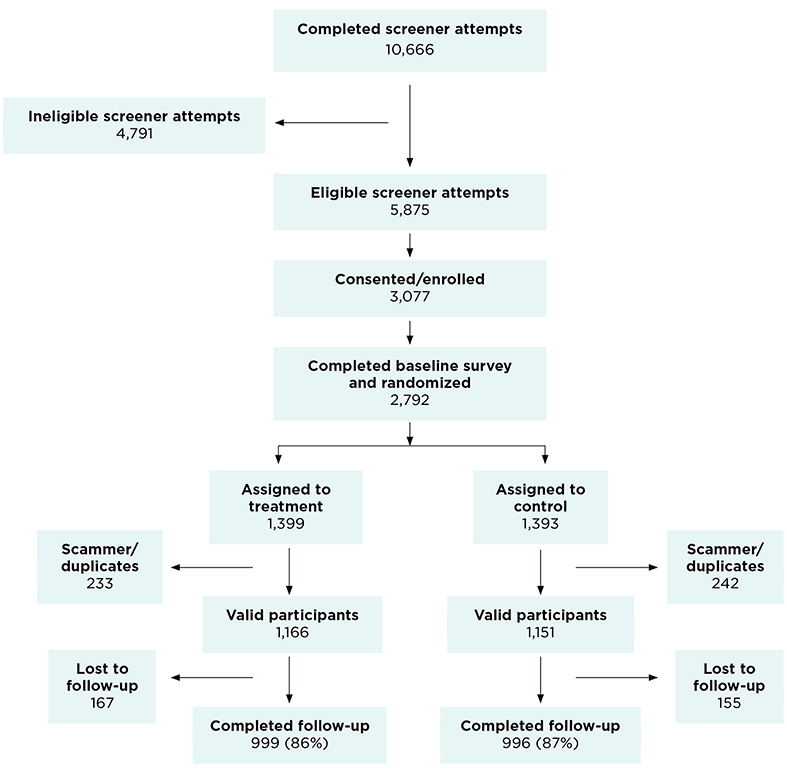

CONSORT Diagram

Participants were recruited through ads on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Once participants clicked on an ad, they were taken to a screener. Participants completed the screener and, if they met eligibility criteria, were directed to an online enrollment form, consent form, and baseline survey. Upon completion of the baseline survey, participants were randomized to either the intervention or comparison group.

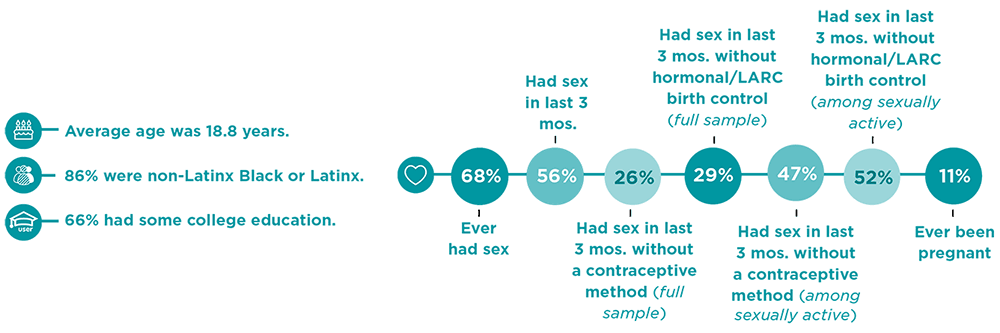

Enrollment and demographics

The evaluation team enrolled 2,317 participants online, most of whom were recruited through Instagram ads. The participants’ characteristics at the time of study enrollment were similar for the intervention and comparison groups.

Characteristics of the intervention sample:[1]

[1] “Hormonal/long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods” include the following methods: birth control pills, the shot (for example, Depo Provera), the patch (for example, Ortho Evra), the ring (for example, NuvaRing), IUD (for example, Mirena, Skyla, or Paragard), and implants (for example, Implanon or Nexplanon).

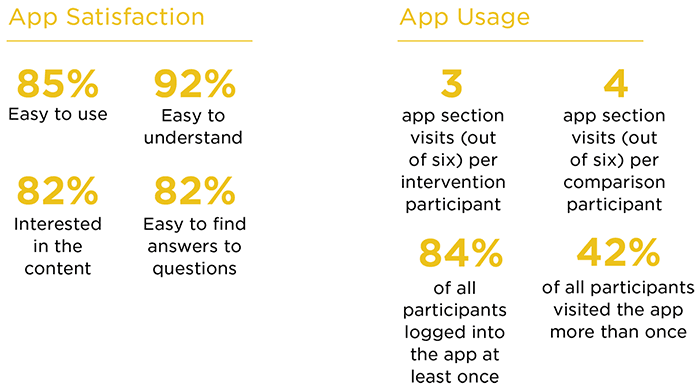

Participant app usage

Although participants were asked at enrollment to view the app, not all participants did. Since Pulse was an online evaluation, we relied on participants to view the app on their own time. We analyzed app usage data to see whether participants viewed the app, and how often they did so.

Design and methods

- Participants were randomized to either the intervention or comparison group using a permuted block design.

- The evaluation team used ordinary least squares regressions to assess the impact of Pulse. All analyses controlled for the baseline measure of each outcome, sexual experience at baseline, age, and race and ethnicity.

- We adjusted standard errors to account for the permuted block randomization and multiple hypotheses testing within domains.

Evaluation successes

- The evaluation team recruited a large, racially diverse sample completely online in less than one year. Of the 1,304 participants in the first cohort, 76 percent were Black and/or Latinx. All 1,013 participants in the second cohort were Black and/or Latinx.

- Most participants stayed in the study despite never having personal contact with study staff. Eighty-six (86) percent of the sample completed the follow-up survey.

- The intervention and comparison groups were equivalent on important characteristics at the beginning of the study. Both groups were comparable on age, race and Hispanic ethnicity, employment, educational achievement, parental educational achievement, relationship status, number of children, recent exposure to reproductive health information, current participation in another teen pregnancy prevention program, and nearly all behavioral, knowledge, attitudes, and intentions outcomes.

- At the end of the study, more intervention group participants than comparison group participants remembered receiving information about reproductive health from any source. Six weeks after enrolling in the study, more intervention than comparison group participants said they had received information about abstinence from sex (57 vs. 51 percent), how to say no to sex (72 vs. 66 percent), how to talk to a partner about using birth control (67 vs. 59 percent), and methods of birth control (81 vs. 74 percent).

Lessons learned

Throughout the initial evaluation of the Pulse study, Child Trends identified several challenges and successes:

- Streamlining the enrollment process improved recruitment numbers. The evaluation team changed the process so that users were automatically directed from social media ads to the screener, instead of to the study landing page. In addition, we changed the format of the screener questions so they were all located on a single page instead of a “question-per-screen” format. Since most participants took the screener on their phone, this resulted in a large increase in screener completions—from 9 percent to over 90 percent.

- Targeted recruitment reduced recruitment costs. By using targeted recruitment—for example, by focusing our ad dollars on cities with high concentrations of Black and Latinx populations—we reduced the cost of recruiting a single participant from over $100 at the beginning of the full study to $3 for the last three months of recruitment for the first cohort.

- Targeted recruitment enabled specific sub-groups to be recruited. Enrolling such a large sample of racial and ethnic minority participants in such a narrow age group was a major study achievement. We carefully refined the content of the social media ads and the specified audience to target sub-groups, which resulted in a higher influx of participants within the preferred sample populations (18- and 19-year-old Black and/or Latinx women).

- Identifying and removing ineligible participants is critical for online enrollment. We developed a streamlined procedure to identify and remove scammers (participants who did not meet our eligibility criteria in their first screener attempt, but who changed their responses until they passed the screener) and duplicate users (participants who enrolled more than once) from our study sample. In total, we identified and removed 475 scammer or duplicate users, which accounted for 17 percent of the 2,792 randomized participants.

Contributors: Genevieve Martínez-García, Milagros Garrido, Nicholas Sufrinko, and Emily Miller.

This publication was made possible by Grant Number TP2AH000038 from the Office of Adolescent Health (OAH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the OAH or HHS.

References

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(9):843-852.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;2018.

- Results from the OAH Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program. Washington, DC: HHS Office of Adolescent Health;2015.

- Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Driscoll A, Drake P. Births: Final data for 2017. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;2018.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube