Better Data on Homelessness Needed as Young Adults with Foster Care Experience Transition to Adulthood

For more information on the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD)—and on what NYTD data can tell researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders about the experiences and well-being of older youth in foster care as they transition to adulthood—click here.

The goal of our nation’s child welfare system is to ensure permanency for children removed from their homes, typically via reunification with their families; legal, permanent guardianship; or adoption. When permanency cannot be attained for older youth in foster care, preparations for independence and self-sufficiency become paramount. In federal fiscal year (FY) 2018, nearly 18,000 young people aged out of foster care. As these young people leave care, they often do so without a stable network of people and resources upon whom they can rely for support. Even young people who do achieve permanency before age 18 may still experience some of the residual challenges associated with being in care. Child welfare agencies and local providers must offer supports to older youth with foster care experience to allow them to thrive (not merely survive) as they transition into young adulthood. These supports should include connecting young people to safe, accessible, and affordable housing options. Visit the series landing page for more information about efforts to understand the unique needs of young people transitioning from foster care.

We know—from existing data and from these new findings—that homelessness, particularly after age 17, creates challenges as young people prepare for adulthood. Even absent any foster care experience, young people without stable housing more often experience lower educational attainment, higher unemployment, and reduced physical and mental well-being, relative to their stably housed peers. Chronic, longer spells of homelessness create additional challenges in each of these areas. For young people with foster care experience, past research also shows longer spells of homelessness than their peers who were never in foster care.

NYTD report to Congress

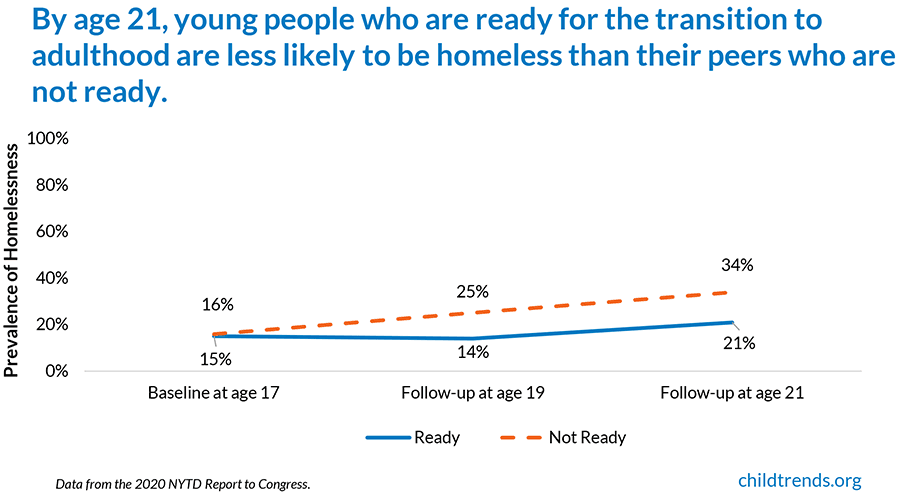

For the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD), a new cohort of 17-year-olds is started every three years with a survey in that baseline year, plus a follow-up survey at age 19 and a final follow-up at age 21. The Administration for Children and Families’ (ACF) recent report to Congress on NYTD includes outcomes for the second cohort of young people who were first surveyed in FY2014 for their age 17 baseline. The report further highlights the link between homelessness and early indicators of readiness for a successful transition to adulthood by age 21. Young people who demonstrated indicators of readiness—a high school diploma/GED, in addition to being enrolled in school or employed at age 21—were less likely to be homeless than those without these indicators. Homelessness rates for both groups of young people (those with and without indicators of readiness) were nearly identical at baseline but diverged significantly—by more than 10 percentage points—at both follow-up surveys. These differences may be even larger given that the NYTD survey language does not include “couch surfing,” a common but more hidden form of homelessness in which a young person temporarily stays with various friends or family. One estimate of young people’s experiences after leaving care found that, by age 23 or 24, nearly 28 percent reported couch surfing since leaving care.

Our analysis

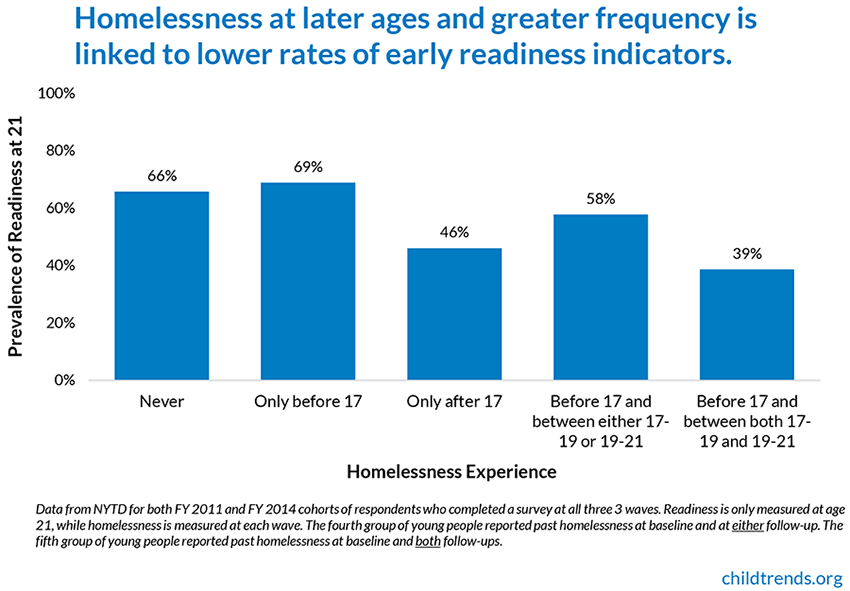

In contrast to the NYTD report framing, which compares homelessness rates between young people with early indicators of readiness for adulthood and those without such indicators, our analysis looks at readiness rates across different homelessness experiences. We include only those young people who responded to all three waves of the NYTD survey within both NYTD cohorts (FY 2011 and FY 2014).[1] Homelessness is measured at each wave while readiness is measured only at age 21, so the patterns below reflect readiness indicators at age 21 for young people with different homelessness experiences. Our analysis shows that homelessness from ages 17 to 21 is linked to lower rates of early readiness indicators. Young people who reported being homeless after age 17 (i.e., at age 19 and/or 21) were less likely to be ready for the transition to adulthood at age 21 than their peers who only reported homelessness before age 17 or were never homeless. Young people who reported homelessness in all three survey waves (i.e., before age 17 and between both ages 17-19 and ages 19-21) had the lowest rates of readiness at age 21, at 39 percent.

What we don’t know

While we know that indicators of readiness for adulthood and homelessness from ages 17 to 21 are related, the data cannot tell us the frequency or duration of homeless spells. The NYTD survey language simply asks young people whether they did or did not experience homelessness since the last survey.[2] Young people in this age range are highly mobile, with one study noting that young people who aged out of foster care moved an average of 2.3 times per year after leaving care. Identifying chronic homelessness is difficult without knowing the length or frequency of episodes. When young people move often, they are also harder to locate, which likely leads to an undercount of the true number of young people experiencing homelessness.

Even with the limitations in the current NYTD data, policy and practice need to focus resources on connecting young adults to stable housing options, especially from ages 17 to 21. Once young people establish foundations for success, such as stable housing, they can progress from such initial tasks for surviving into the new phase of tasks that are focused on thriving. As policymakers, practitioners, and local child welfare systems work to better understand the experiences of young adults as they transition out of foster care, the collection of robust, high-quality data is a key step in identifying reliable benchmarks to measure improvement over time. Beyond this step, adding questions on couch surfing and the length of homelessness spells would allow system-level and community supports to be better tailored to addressing gaps that contribute to homelessness. In short, better data leads to better policy and practice.

The next brief in this series explores education and employment outcomes for young people transitioning from care.

References

[1] While this method compares only young people whose full history is known, it may undercount homelessness because of lower overall response rates and because there are fewer young people from states that only follow up with a random sample of their eligible baseline population.

[2] Respondents are surveyed at 17 then followed up with at ages 19 and 21. The baseline survey asks about homelessness at any point up to age 17. The follow-up surveys both ask about homelessness in the past two years (between 17 and 19, then between 19 and 21).

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTube