Adapting an In-person Sexual Health Program for a Virtual Setting

Authors

Jenita Parekh, Alison McClay, and Bianca Faccio contributed equally to this work.

The COVID-19 public health pandemic pushed many sexual health programs to quickly shift planned in-person programming to virtual implementation, but many programs lacked guidance or previous experience on how to do so. In July 2020, Child Trends was awarded a three-year grant from the Office of Population Affairs to implement and rigorously evaluate El Camino, a sexual health promotion curriculum focused on goal-setting activities for participants. Child Trends, the developers of El Camino, and Identity, Inc., our implementation partner, planned to implement El Camino in-person in eight Montgomery County, MD, public high schools starting in Fall 2020. However, as schools remained closed due to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, Child Trends shifted efforts to adapt the El Camino curriculum for virtual implementation from September 2020 to February 2021.

After pilot testing in two high schools in November and December 2020, El Camino was implemented in all eight high schools starting in February 2021 and throughout the Spring 2021 semester. Lessons learned from virtual implementation this year could be helpful in the future for students who otherwise may not be able to receive in-person programming, including teens who have previous commitments that keep them from going to an in-person site, students who do not have access to resources such as transportation to an in-person site, or students who will continue remote learning after full in-person schooling starts again.

This brief describes Child Trends’ process for adapting the in-person El Camino curriculum for virtual implementation. Child Trends collaborated with multiple partners to adapt, pilot test, and make curriculum revisions while preserving the core components of the in-person curriculum. The process was iterative and continued while full implementation was underway. We highlight key takeaways learned in piloting and implementing our virtual curriculum.

The El Camino Sexual Health Promotion Curriculum

Child Trends originally developed and tested El Camino from 2015 to 2018. El Camino is a goal-setting sexual health promotion curriculum that is available in both English and Spanish and targeted toward Latino youth. Throughout its eleven 45-minute lessons, El Camino encourages youth to set goals, make informed sexual and reproductive health choices, and have healthy relationships. Preliminary research on El Camino’s in-person implementation suggests that youth across seven cities responded well to the curriculum and that participation led to changes in their sexual health attitudes and knowledge. Additional information about El Camino and links to the English- and Spanish-language curriculum materials (including virtual adaptation instructions) can be found here.

Key Recommendations and Findings

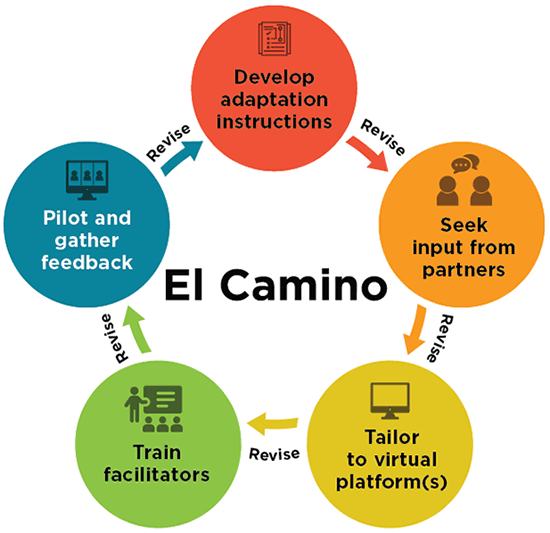

Adapting the El Camino curriculum for virtual implementation required an iterative approach that prompted changes to the curriculum itself, as well as changes in how the program was implemented. Implementation partners provided input at every stage of the revision process. Based on our experience, we recommend the following steps for program developers and implementers—or others planning to implement existing sex education programs virtually—to successfully adapt a curriculum for virtual implementation:

- Use a team-based approach to revise the curriculum, seeking input from implementation partners on proposed virtual adaptations.

- Develop clear virtual adaptation instructions for facilitators.

- Tailor virtual implementation instructions to the technology platform that implementation partners and program participants are most comfortable using (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams, etc.).

- Train implementation staff virtually on the updated curriculum.

- Pilot test the virtual curriculum and gather facilitator and participant feedback to improve implementation. Pilot testing allows facilitators to practice virtual implementation and lets participants and facilitators highlight areas for improvement.

- Plan for multiple iterations of revision and training following the pilot.

Implementing a curriculum virtually also required changes and considerations beyond the virtual adaptation edits made to the curriculum. Our adaptation and implementation process revealed five key lessons:

- Virtual implementation takes more time than in-person implementation.

- Having more than one facilitator helps alleviate technical challenges with virtual implementation: One facilitator can deliver the curriculum while the other monitors technological needs.

- Building adequate rapport and relationships between facilitators and youth requires time, effort, and creativity.

- Student privacy may be more limited virtually because students are at home around family or in public settings.

- Engaging youth during virtual programming takes more effort than in-person implementation.

Process to Adapt an Existing In-person Curriculum for Virtual Implementation

Child Trends allocated five months for the curriculum adaptation process, which included a five-week pilot. While this brief presents the steps sequentially, adapting the curriculum was an iterative process between those developing and writing the curriculum content and the program implementers. We continued to make small adaptations to the curriculum as we learned more about how students were responding to and engaging with the curriculum in a virtual setting.

Processing for Adapting a Sexual Health Curriculum for Virtual Implementation

Recommendations for Adapting a Curricula to Virtual Implementation

Use a Team-based Approach to Revise the Curriculum.

Child Trends worked with a curriculum writer[1] and implementation partners to identify necessary adaptations to the curriculum, pilot the curriculum with a group of youth, and revise the virtual adaptations based on youth and facilitator feedback. Each member of the team had a unique role in the revision process:

- Curriculum developers offered in-depth knowledge of the curriculum, identified core components, and identified where and how to adjust.

- Program implementers provided on-the-ground knowledge of what will work with adolescents.

- The curriculum writer crafted clear instructions for a virtual setting.

Develop Clear Virtual Adaptation Instructions for the Curriculum.

Child Trends worked with a curriculum writer[2] to draft specific and clear virtual instructions on how to adapt lesson activities. These instructions were incorporated within callout boxes throughout the existing curriculum. Child Trends and the curriculum writer worked collaboratively to identify areas where additional instruction was needed to offer a virtual alternative to an in-person activity, such as the use of breakout groups or Zoom reactions in place of verbal or physical student responses. For example, several activities (such as a condom demonstration lesson) were originally dependent on in-person demonstrations, so we identified instructional demonstration videos from high-quality, scientifically accurate sources to deliver the information.

Virtual Adaptation

Substituting a Sock for a Condom

It might be uncomfortable for facilitators and students to practice this activity with condoms in a remote setting. If this is the case in your community, please adapt this activity using a sock. For information about how to demonstrate using a condom with a sock, see this website.

Facilitator Demonstration

Conduct the condom demonstration as written in this activity. Be sure you are close enough to your webcam so students can see what you are doing.

During virtual implementation there will be no student practice section.

Instead of asking students to practice, review the steps using the following videos:

The in-person El Camino curriculum included printed student workbooks used during lessons. The adaptation team converted the student workbooks to fillable PDF documents so that students could electronically complete lesson materials during virtual lessons. For students who did not have access to a device that would allow them to easily complete a PDF while participating in a Zoom lesson, we also developed PowerPoint presentations that incorporated critical text and information presented in the student workbooks.

Seek Input from Implementation Partners on Virtual Adaptations.

Child Trends gathered feedback from facilitators about which types of virtual adaptations might work with the program’s target population. Facilitators from Identity, Inc. were already implementing several programs virtually due to COVID-19 and provided implementation strategies informed by their recent experiences. For example, they recommended using visuals and PowerPoints because adolescents had trouble maintaining focus on content in a virtual setting. Identity staff also recommended using breakout rooms for smaller group discussions and to stimulate greater student engagement.

Tailor Virtual Implementation Instructions to the Technology Platform that Partners and Program Participants are Most Comfortable Using.

Based on input from Identity staff, we tailored the curriculum to Zoom, a platform with which facilitators and students were already familiar. Although incorporating additional platforms (such as Mural or Jamboard) may have enhanced activities, Identity staff recommended utilizing a single platform to reduce the amount of time staff would need to explain the technology, complete each activity, and troubleshoot technological difficulties. Facilitators also provided input on which Zoom features worked best for implementation. For example, when compiling youth feedback on fill-in-the-blank activities, facilitators noted that Zoom’s whiteboard features were difficult and awkward for students and facilitators to navigate. Instead, facilitators shared their screen with a PowerPoint slide and asked youth to share their responses—either aloud or via chat—while the facilitator typed them into the slide.

Train Implementation Staff on the Virtual Curriculum and/or Curriculum Adaptations.

Child Trends conducted a training on the revised El Camino virtual curriculum with facilitators from Identity (including several who had implemented the curriculum in-person). We adapted our in-person training for a virtual setting and conducted it on the same platform (Zoom) that the facilitators would use for virtual implementation. We tailored the training to build on the facilitator’s existing knowledge of the online platform. During the training, we gave an overview of the differences between in-person and virtual delivery, pointed out callout boxes in the instructions, demonstrated how activities were to be implemented virtually (focusing on those that were most complex to implement in a virtual setting), and reviewed general virtual implementation tips (Appendix I of the front matter materials). Throughout the training, facilitators practiced implementing activities using the newly created PowerPoint slides and revised curriculum.

We found that virtual trainings required an additional three hours of training time (in-person training had taken 12–15 hours) to allow facilitators to test and become comfortable with the technology used in the lessons and with engaging participants virtually. Additionally, Identity facilitators worked together to co-implement El Camino; we learned that these facilitators benefitted from practicing together during the training.

Pilot Virtual Lessons and Gather Facilitator and Student Feedback to Improve the Curriculum and Implementation.

Identity staff virtually piloted each lesson of the revised curriculum with classes from two high schools, while Child Trends staff observed. The piloting process served to:

- Prepare educators for their role as facilitators in a virtual setting.

- Assess implementation fidelity and quality in a virtual setting.

- Test the clarity of the virtual curriculum instructions.

- Ensure that revised activities were clear, worked in a virtual setting, and were well-received by youth.

Following each pilot lesson, Identity facilitators led a debrief with students and Child Trends led a debrief with Identity. Child Trends used feedback from facilitators and students to further revise virtual curriculum activities and strengthen virtual adaptation instructions. Lessons from the virtual implementation are further discussed below.

Plan for Multiple Iterations of Revision and Training.

The virtual adaptation process requires ongoing revisions. Child Trends revised the curriculum after the pilot and trained a new group of facilitators, who in turn provided additional feedback about the virtual instructions. We clarified instructions after observing facilitators implement activities and continued to make minor revisions throughout the large-scale implementation of the virtual curriculum. We obtained ongoing feedback through debriefing sessions with facilitators, who shared which aspects were going well and where there were opportunities for improvement.

Lessons Learned During Virtual Implementation

Based on the Fall 2020 pilot and our full-scale implementation of El Camino during the Spring 2021 semester, the following virtual implementation lessons stand out:

Virtual Implementation Takes More Time than In-person Implementation.

Implementing the curriculum lessons in a virtual setting took longer than the originally allotted 45 minutes per lesson—usually 50 to 55 minutes. Facilitators needed to spend time engaging youth early in the lesson to ground them in the curriculum and to wait for late comers to join. Additionally, it took longer to complete lesson content while presenting materials via PowerPoint and incorporating features such as reaction emojis and the chat box. Furthermore, there were inevitably connection glitches. Facilitators (in partnership with the schools) increased the lesson time to an hour—adding in a 15-minute buffer to address any issues that arose. In addition, curriculum instructions specify which discussion questions and talking points to prioritize and indicate activities that are optional, and the training materials provide guidance on ensuring fidelity if facilitators run short on time.

Having More Than One Facilitator Alleviates Technical Challenges with Virtual Implementation.

Identity had two facilitators implement El Camino, which allowed them to assign a secondary facilitator to serve in a logistics role to allow the primary facilitator to focus on lesson delivery. The logistics person was able to implement virtual features and troubleshoot any technological issues that arose without major interruption or time delays to the lessons. Implementing virtual programs in school settings may also require more than one facilitator to satisfy online security and student privacy requirements. For instance, some school districts require that each breakout room has an adult staff member, so breakout groups are limited to the number of facilitators on a call.

Building Adequate Rapport and Relationships Requires More Time, Effort, and Creativity.

It is especially important to build positive and trusting relationships with youth when discussing the sensitive and personal topics covered in sexual health promotion curricula. However, building rapport is more difficult in a virtual setting. During lessons, facilitators made an effort to check in with participants as they joined, validated participants’ answers to prompts, and vocalized appreciation for participation. Facilitators would often send participants a direct chat or a text immediately following a lesson to thank them for their participation. Outside of lessons, Identity facilitators were more purposeful and active in forming connections and establishing themselves to participants as a trusting and available adult. Identity facilitators adapted their usual forms of regular contact with students through individual check-in calls and text messages that followed up on youth comments or facilitator observations that occurred during program time. Facilitators shared that these informal check-ins allowed them to connect with youth, which led to more consistent attendance and sometimes greater participation in the next lesson.

Students’ Privacy May Be More Limited in Virtual Settings.

As noted previously, we learned during the pilot that many students did not feel comfortable having their cameras on, in part because many of them attended lessons either with family members in the room or in public spaces. Not all students will experience these challenges in the exact same ways; therefore, it is critical that facilitators be welcoming and accommodating of challenges while also not assuming that students’ environments are all the same. Participants were not required to use video and facilitators measured engagement based on youth responses to the material. Given the lack of privacy for some youth, sexual health visuals and content appearing on a laptop or other handheld device might be concerning to youth (and their family members). To address this challenge, we included a trigger warning before any images or content that might make students uncomfortable. Facilitators gave youth time to put headphones on, adjust their screens, or move to a different location. Additionally, in a virtual setting, students could not approach facilitators at the end of the class to ask private questions about sexual health. Facilitators encouraged private messages when appropriate, provided their cell phone numbers and email addresses to youth, used an anonymous virtual question box via Google Forms, and were the last to log off after each session in case youth wanted to ask questions that they were uncomfortable sharing with the whole group.

Engaging Youth Virtually Takes More Effort than During In-person Implementation.

Learning through an online platform can be draining and challenging for adolescents. Facilitators found that, with virtual implementation, they missed bodily cues indicating that youth wanted to participate (or not), and that the added requirement of having to mute or unmute on Zoom led to fewer youth participating. To address this challenge, facilitators began each session with an icebreaker or a grounding exercise. Visuals and PowerPoint presentations allowed facilitators to present detailed, technical material in a more engaging way and helped keep youth focused. Features like chat boxes or Zoom reactions also allowed facilitators to keep youth engaged throughout the lesson. This kind of nonverbal engagement was particularly helpful for youth who were less likely to speak or have their cameras on in the session. During periods of silence and nonresponse, some facilitators would ask youth if they were not responding because they were unclear about the lesson content. This practice not only helped with lesson engagement but also provided helpful information for implementation and identified potential needs for curriculum revision.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented many new challenges to program implementation—with perhaps the most pressing being how to adapt curricula designed for in-person implementation into engaging and effective programming that can be delivered in virtual or hybrid (in-person and online) settings. With one sexual health promotion program—El Camino—Child Trends took an iterative approach to revising the program curriculum. We continued to learn to adapt when activities did not work in a virtual setting, or when facilitators needed further training and instructions. Revisions continued as we implemented the curriculum with more youth.

Through our pilot implementation, we learned that virtual programming takes more time than in-person programming, so activities must be shortened if more time cannot be allocated. Technical challenges will arise, but keeping lessons on one virtual platform and having two facilitators can alleviate some of these issues. Finally, the process for learning, engagement, and relationship building with youth is vastly different online than in the classroom. Facilitators should anticipate that many participants will not be attending lessons in a private setting and that, as a result, many will not be on video. It is therefore critical to accommodate this by incorporating chat and reaction features. Additionally, facilitators may need to reach out to participants individually (and outside of lesson time) to build adequate rapport.

The benefits of adapting a program for virtual implementation are not limited to the current pandemic and could have many uses in the future. For example, virtual implementation allows after-school and community-based programs to reach youth who are unable to attend in-person sessions for a variety of reasons, including (but not limited to) program cost, transportation, desire or need to work, and family or other responsibilities that would keep youth from participating. Virtual implementation also does not require that facilitators be geographically close to participants: Youth and facilitators with access to a device and a stable internet connection can join programming, regardless of their physical location. Youth who may be uncomfortable discussing sexual and reproductive health topics with a group of peers in-person may be less anxious to participate online. Additionally, facilitators can be creative with their instruction, utilizing technology in new or different ways. Given the uncertainty of the post-pandemic world, it is important that sexual health promotion curricula have the flexibility for virtual implementation to ensure that youth receive the education they need to promote sexual health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our curriculum writer, Lori Rolleri; Identity, Inc. staff and facilitators; and Jane Finocharo, Isai Garcia-Baza, and Salomon Villatoro at Child Trends for providing clear instructions, thoughtful feedback, and curriculum support throughout the adaptation process. The authors would also like to thank Kate Welti at Child Trends for her careful review and feedback on an initial draft of this research, in addition to Kristin Anderson Moore and Hannah Lantos at Child Trends and Roshni Menon and Alexandra Warner at the Office of Population Affairs for their expert reviews of this product.

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1 TP2AH000077-01-00 from the HHS Office of Population Affairs. Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services or the Office of Population Affairs.

Notes

[1] We recognize that not every program will work with a curriculum writer, but every program will benefit by working with various stakeholders in the revision process. Implementers can contact the program developer and engage community members and other field experts when revising a curriculum.

[2] We recognize that not every program will work with a curriculum writer to develop these instructions, but every program will benefit by having clear instructions for how to deliver program materials online. Implementers can contact the program developer to see whether they have released guidance for virtual implementation or develop their own virtual adaptation instructions for specific activities.

Suggested Citation

Parekh, J., McClay, A., Faccio, B., Gates, C., Garcia, J., Coryell, A., & Manlove, J. (2021). Adapting an in-person sexual health program for a virtual setting. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/5085e1747r

Authors

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram