Resources and Strategies for Lifting Community Voices

Principles of community-engaged research and practice

Community can be defined in various ways—as groups of individuals connected by geographic proximity (e.g., neighborhood residents), by professional interests (e.g., educators), by shared experiences (e.g., nursing mothers), or through common cultural and social identities (e.g., Black youth). Understanding community in this diverse and inclusive manner allows for a broad range of engagement approaches, ensuring flexibility to fit different contexts and groups.

Effective community-engaged research and practice draw on communities’ strengths and assets, rather than focusing on their deficits. There are various ways to engage communities, including strategies in which community members lead the work or provide guidance and advice. Regardless of the method, all community-engagement strategies should be anchored in three core principles: equity, shared decision making, and mutual respect.

- Equity: All perspectives, especially those of marginalized or underserved groups, should be valued and represented. Ensuring that every voice is heard fosters a more inclusive and just process.

- Shared decision making: Decisions should be made through a transparent process that allows for input from all who are involved. This ensures that all parties have a say and that the decision-making process allows for healthy conflict and dissent, ultimately leading to better, more accepted outcomes.

- Mutual respect: Every participant should be treated with dignity and civility. Respecting each individual’s contributions and perspectives fosters trust and positive relationships between researchers, practitioners, and community members.

By fostering principles of equity, shared decision making, and mutual respect, community engagement can become a transformative process that empowers communities, respects their voices, and leads to more meaningful and impactful outcomes.

Steps to conduct community-engaged activities on PCRs

We applied the principles of effective community engagement in our PCR activities (i.e., community mapping activities and focus group discussions on PCRs) and carried out these activities in three steps, shared below. Because we conducted the PCR activities as a research study involving human subjects, we first obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. However, PCR activities that are not conducted for research purposes may not require IRB approval. If you are not certain whether IRB approval is required, these guidelines from the Office of Population Affairs may be useful.

Step 1. Identify community partners and participants.

Because community can be defined in various ways, it is important to thoughtfully select participants for PCR activities based on the specific needs and context of your research, practice, or leadership. Our goal was to address research gaps on PCRs for Black children and youth, so we began by reaching out to organizations with well-established relationships with Black families and emerging adults. These organizations were chosen based on their trust and rapport within the community, their successful history of community-based initiatives, and their direct connections to the focal populations. This strong foundation of prior collaboration was key to the success of our PCR activities.

Our community partners assisted with multiple aspects of the process, including selecting the dates, sites, locations, and modes of communication (in-person or virtual) for the PCR activities. They also helped us recruit participants who were willing to share their experiences with PCRs. We made sure to recruit a diverse group of participants, considering factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status to incorporate a broad range of experiences. We compensated focus group participants for their time and expertise in the form of gift cards; however, the type and amount of the incentive should be determined in collaboration with key partners.

To help toolkit users recruit participants, we have included examples of recruitment flyers in the “Tools and Materials” section below. One flyer was used to recruit participants for PCR activities with families of children from birth to age 17, and the other focused on emerging adults ages 18 to 25. These flyers contain key information for recruitment, including the purpose of the PCR activities; the focal population of interest; the location, date, and time of the activities; the duration of the session; and contact details for the community liaison or session facilitator. Toolkit users can customize these flyers to fit their specific needs and recruit participants from their own communities.

Step 2. Conduct PCR activities.

After recruiting participants and scheduling a session, PCR activities can begin. Each session starts with an overview of the PCR activities, including a definition of “protective community resources,” an explanation of participants’ rights, and assurances that their responses will remain anonymous and confidential in all products resulting from the discussion. Following this introduction, participants are given the opportunity to ask questions and informed of their right to withdraw from the PCR activities with no negative consequences. If conducted as research, each participant should receive a copy of an informed consent document outlining these details about their rights. Compensation can be provided either at the beginning or end of the PCR activities, depending on the preference of the session facilitator (approximately 10 minutes).

Next, participants are asked to choose a pseudonym that they will use throughout the session to maintain confidentiality. For virtual focus groups, participants receive instructions on selecting a pseudonym and joining the recorded and transcribed session anonymously using Microsoft Teams. A short survey is then administered to collect demographic data from each participant (approximately 5 minutes). This survey collects information such as age and gender to ensure diversity within the group and provide context for later analysis of data from the PCR activities.

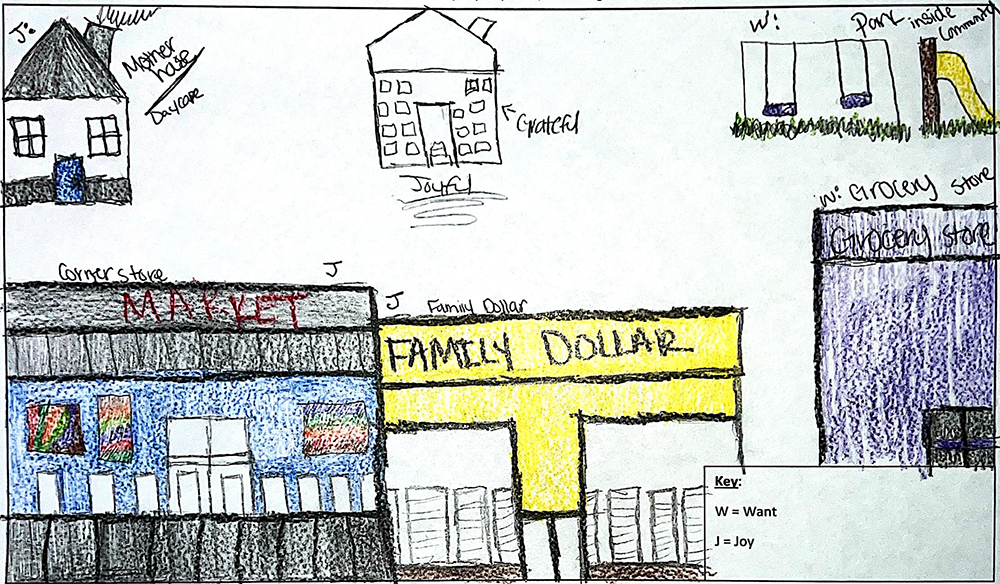

In the first activity, participants are asked to depict the PCRs (the “people, places, and things”) in their communities that promote their well-being. In-person participants are provided with colored pencils, and a PCR map tool, while virtual participants use a digital drawing tool called Sketchpad. They are asked to center their homes on their maps and define their “community” as they see fit—without being restricted by geographic boundaries (approximately 10 minutes). Afterward, the facilitator engages participants in an audio-recorded group discussion about the elements they’ve placed on their maps, ensuring that each participant has an opportunity to share their perspective (approximately 20 minutes).[1] Focus groups are intentionally kept small (5 to 7 participants) to allow for this level of individual attention.

The second activity asks participants to depict on their maps the protective resources they want in their communities but which are currently inaccessible, marking these resources with a “W” to distinguish them (approximately 10 minutes). This is followed by another audio-recorded group discussion, where participants can share their thoughts on the barriers to accessing these resources (approximately 20 minutes).

Next, participants identify one PCR on their maps that they associate with joy for themselves or their families, marking it with a “J” (approximately 5 minutes). They are then asked to share a story or experience related to this PCR, reflecting on its emotional significance (approximately 20 minutes). This discussion is also audio-recorded. (See the example of a participant’s map below.)

Figure 1. Community map example

The session concludes with a thank you to participants, an opportunity to answer any final questions, and a request for the locations of some of the PCRs mentioned to aid in data analysis and interpretation (approximately 10 minutes). The total time allotted for each session should be about two hours.

Sample Agenda for PCR Activities

(Note: Approximately 2 hours should be allotted for the entire PCR session.)

1. Welcome and Introduction (10 mins.)

2. Demographic Survey (5 mins.)

3. Existing PCRs

a. Mapping Activity (10 mins.)

b. Focus Group Discussion (20 mins.)

4. Wanted PCRs

a. Mapping Activity (10 mins.)

b. Focus Group Discussion (20 mins.)

5. PCRs and Stories of Joy

a. Mapping Activity (5 mins.)

b. Focus Group Discussion (20 mins.)

6. Close (10 mins.)

Below, we provide editable data collection materials, including an informed consent document, demographic survey, instructions for virtual focus group participation, the focus group protocol and questions, and the PCR map tool.

Step 3. Analyze the data

Analyzing data—in this case, the information from the PCR activities—entails interpreting them to deepen or expand one’s understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The PCR activities described in the previous step combine survey, visual, and oral data, a method known as triangulation that enhances comprehension by drawing on multiple sources of information. To analyze the data, we developed tools and processes that can be used by researchers, practitioners, and leaders with basic data analysis skills to better understand PCRs for specific groups.

- Survey data analysis: The survey data were collected using Microsoft Forms and then downloaded and analyzed descriptively using Microsoft Excel. We calculated simple percentages and averages for demographic characteristics such as age, income, place of birth, sex/gender identity, ZIP code, and other relevant factors. This helped us paint a broad picture of the participants’ profiles.

- Map data analysis: For counting, organizing, and describing the PCRs included on participants’ maps, we created an analytical tool organized into primary categories: “people,” “places,” and “things.” Each primary category has secondary categories that capture specific types of resources. For example, under the primary category “places,” we include secondary categories like parks, community centers, and schools. The tool also provides a designated space to include examples and notes for the secondary categories.

- Focus group data analysis: Focus group data were first transcribed. For in-person focus groups, we downloaded the audio recordings and transcribed them using the dictation feature in Microsoft Word, while virtual focus groups provided automatic transcriptions through Microsoft Teams. After transcriptions were reviewed and edited for errors, we analyzed the text to identify key themes (i.e., recurrent ideas and patterns) in the data.

Our team used a collaborative process to both develop the analytical tools and conduct the analysis. However, data analysis can also be done independently or with the involvement of community partners and participants. Regardless of the approach, it is essential to involve community partners in reviewing early findings to ensure that the interpretations accurately represent participants’ voices, perspectives, and experiences. This feedback loop serves as a way to verify the trustworthiness of your findings.

Using findings to promote thriving communities

Whether you are a researcher, practitioner, or community leader, the findings from PCR activities can be a powerful tool to promote thriving communities. These findings provide insights that can guide decisions, improve services, and inspire collective action.

- Researchers can use the findings to drive change by sharing their results through research publications, presentations, and tools. These resources help others better understand PCRs for marginalized and underserved groups, while also contributing to the broader body of knowledge about how communities can be strengthened.

- Practitioners can apply the findings to improve or expand existing services or collaborate with other professionals to integrate services more effectively. The goal is to better meet the needs of the individuals and families who rely on these services, ensuring that the resources available are comprehensive and accessible.

- Community leaders can use the findings on PCRs to identify opportunities for community and systems change. For example, if participants identify parks as critical PCRs but express a desire for better lighting or updated play equipment, this can become a focus for collective community action. By collaborating with key actors—such as elected officials, residents, and service providers—community leaders can prioritize and address these areas for improvement.

Collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and community leaders in interpreting and applying the findings on PCRs can enhance the collective impact of this work, ensuring that all voices are heard and that actions taken are meaningful, sustainable, and rooted in the lived experiences of those directly affected by the issues.

How Community Leaders, Practitioners, and Researchers are Building Protective Communities

- Young Leaders Tackle Key Issues That Affect Black Children and Families’ Well-being (or watch on YouTube)

Tools and materials for PCR focus groups

Below, we provide tools and materials that can be used for participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. These resources are designed to help you effectively implement and analyze your own PCR activities and can be adapted to fit your specific needs.

1. Recruitment flyers: Examples of flyers to recruit participants for PCR activities

2. Informed consent form: Editable document outlining participants’ rights and study details, ensuring ethical standards are upheld

3. Demographic survey: Example of a survey created using Microsoft Forms to gather basic demographic information from participants

4. Focus group protocol: A comprehensive guide for conducting in-person or virtual community mapping activities and focus group discussions, including sample questions

5. Instructions for joining a virtual focus group: Step-by-step directions for participants to anonymously join a virtual focus group using Microsoft Teams

6. Map tool for in-person PCR activities: A visual tool for participants to map out the PCRs in their lives

7. Map analysis tool: A guide for analyzing the in-person or virtual maps that participants create, helping to interpret the visual data

8. Transcript analysis tools: Spreadsheets for organizing and analyzing data collected during focus groups, including direct quotes from participants

8a. Spreadsheet to analyze focus group discussions on the benefits and joys of PCRs, and areas of contention among participants

8b. Spreadsheet to analyze focus group discussions on wanted but inaccessible PCRs, the risks associated with their absence, and areas of contention among participants

Footnote

[1] We used password-protected recorders to ensure data security.

Suggested Citation

Sanders, M., Martinez, D.N., Winston, J., & Rochester, S.E. (2025). A toolkit for using protective community resources to promote child, youth, and family well-being. Child Trends. DOI: 10.56417/2058t7973j

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram