Recent crises in Flint, Michigan, and East Chicago, Indiana, have made it clear that children in many communities across the United States are still at risk for lead exposure, often in their own homes. This is especially true for children of color living in low-income communities.

While the United States has made great strides in reducing the number of children at risk of lead poisoning, it has failed to eliminate lead hazards completely. This means that thousands of children each year are at risk of suffering from the cognitive and developmental delays that can result from lead exposure.

Children deserve to grow up in environments free of lead contamination. By understanding how children are exposed to lead—and which children are most at risk for exposure—policymakers and leaders at every level of government can plot a course for eliminating lead exposure for children across the United States. For children who have already been exposed to lead, investments in high-quality interventions throughout childhood can help counteract lead’s cognitive and behavioral effects.

Children are exposed to lead in the places where they spend the most time

More than one-third of the nation’s housing stock contains lead paint

One of the most dangerous and widespread sources of lead exposure is lead-based paint and the contaminated dust it generates in homes, schools, child-care settings, and soil.

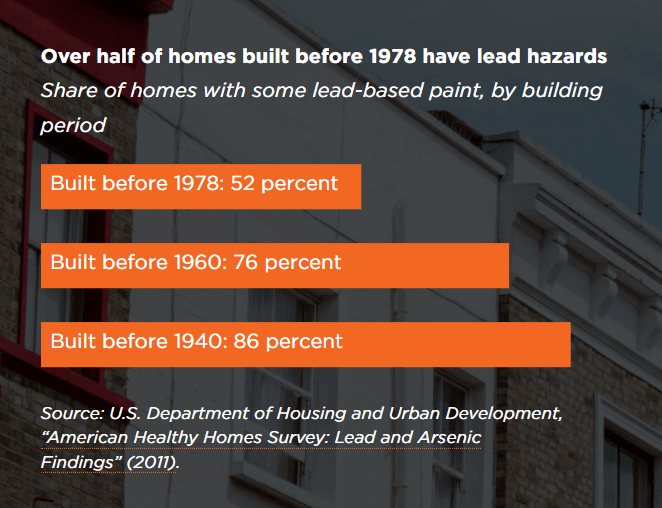

The magnitude of the problem: More than half (52 percent) of all homes built before 1978 have some lead-based paint, according to the 2011 American Healthy Homes Survey from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This number increases for older homes: 76 percent of homes built before 1960 and 86 percent of homes built before 1940 have some lead-based paint. HUD estimates that 37 million residences (more than one-third of the nation’s housing stock) contain lead paint, including 3.6 million homes with young children.

The solution: Removing and/or covering lead paint in homes is the primary strategy for preventing chronic exposure to lead dust. However, these activities themselves can be major sources of lead exposure, which makes it critical to employ safe work practices when repairing or renovating a home with lead-based paint.

How governments and communities are addressing lead paint hazards

The federal Residential Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992 established the federal Lead Disclosure Rule, which requires property owners to reveal any known lead paint hazards to prospective buyers or tenants. It also required the Environmental Protection Agency to publish standards for lead in dust and bare soil at residential properties. A 2010 update to this law established training requirements, standards, and enforcement mechanisms for renovations that disturb paint in buildings built before 1978.

In Rochester, New York, 87 percent of homes were built before 1950, meaning that they are particularly at risk of containing lead paint. Since 60 percent of housing in Rochester is tenant-occupied (versus owner-occupied), the city council passed a 2005 ordinance requiring regular inspections of most pre-1978 rental housing for lead-paint hazards. This inspection is required as part of the city’s certificate of occupancy process for rental properties.

Washington, DC’s Lead Hazard Prevention and Elimination Act of 2008 prohibits the presence of lead-based paint hazards in dwelling units, common areas of multifamily properties, and day care and pre-kindergarten facilities constructed before 1978. To sell or lease a unit, the property owner must prove that no lead-based paint hazards were present within the last year.

To help homeowners pay for permanent elimination of lead hazards, Massachusetts offers income tax credits of $500 and $1,500, depending on a property’s needs, and administers a series of loan programs to support compliance with its lead law. The law requires that any property built before 1978 and occupied by a child under age 6 be “deleaded” by removing or covering lead paint hazards.

15 to 22 million people in the United States get water through lead service lines

Lead can get into water through the corrosion of lead service lines (the part of a water pipe that connects a house or building to the public water main). Pipes are particularly prone to corrosion if the water has high acidity or low mineral content. While lead can leach into water from brass or chrome-plated plumbing fixtures, lead service lines account for the largest share of lead in water, according to research from the Awwa Research Foundation and the EPA.

Children are most at risk of exposure to lead-contaminated water in the places where they spend the most time—in other words, at home, school, and child care facilities.

The magnitude of the problem: EPA research indicates that lead service lines account for the largest share of lead in water. Estimates from a 2016 survey of lead service line occurrence suggest that 5.5 to 10 million lead service lines provide water to an estimated 15 to 22 million people in the United States.

In schools, case studies have found dramatic variation in water lead levels across the country. Some of these case studies found that schools in some cities have water lead levels above the EPA’s action level of 20 parts per billion (ppb). For example, a 2015 study of 63 Seattle schools found lead levels from less than 1 part per billion (ppb) to 1,600 ppb; a 2004 study of Philadelphia schools found that 57 percent of buildings had water lead levels above the EPA’s action level, and 29 percent had water with levels over 50 ppb. Because the EPA’s 1991 Lead and Copper Rule only requires that a sampling of water utility taps be tested for lead, many schools have never been tested.

The solution: Reduce lead in drinking water by removing lead service lines from homes. Similarly, mitigate drinking water hazards in schools and child care facilities.

How governments and communities are addressing lead contamination in water

The EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule established corrosion control—which involves treating water with chemicals to create a barrier between water and lead-containing pipes—as the primary way to reduce lead in water. It mandated that water utilities periodically test lead concentration in 10 percent of customer taps, which are chosen from among those deemed more likely to be at risk of elevated lead levels.

When testing finds lead concentrations exceeding 15 ppb, the utility must evaluate corrosion control practices, conduct public education about lead contamination and exposure, and initiate lead service line replacement. The rule does not require that all customer taps be tested.

Under the Lead and Copper Rule, when water utilities replace lead service lines, they must also offer property owners the opportunity to replace their portion of the line at the same time. Because owners cannot be compelled to pay for replacement of their private lines, the public portion of the lead service line is often all that gets updated.

Research finds that lead concentrations increase during and after such partial remediation, meaning that a more comprehensive replacement is necessary to prevent kids from being exposed to lead in water.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s Lead Service Line Replacement Program requires and finances full replacement of lead service lines if the line is found to be leaking, is damaged during planned construction, or if the utility-owned section of a line is replaced on a planned or emergency basis. The city’s $3.9 million budget for the project includes funds to help pay for replacement of privately owned lead service lines.

Woonsocket, Rhode Island adopted a policy in 1986 that requires builders to replace the entire lead service line when a connected structure is sold, demolished, or replaced.

Michigan’s Children’s Health Insurance Program has an amendment that allows funds to pay for the replacement of water pipes and fixtures in the homes of low-income families with children.

Emissions from small aircraft and factories can contaminate air and soil with lead

Lead is introduced into the environment every day by emissions from smaller aircraft (e.g., piston engine airplanes) that use leaded fuel, factories that use or extract lead in manufacturing processes, and electric power plants that burn coal and other lead-contaminated fuels.

Lead from these sources can enter the top layer of soil, which children might ingest or otherwise be exposed to when it contaminates toys or is tracked into homes. Particular groups of children are at a higher risk of exposure to lead through contaminated soil: Research suggests that children exposed to soil with high concentrations of lead are more likely to be black and low-income, and to live in inner cities without access to safe outdoor play areas free from lead.

Lead produced by mining or smelting processes (which involve the use of high temperatures and chemicals to produce lead from ore) can also contaminate air and soil. As the monetary value of lead has risen on international markets, secondary smelting (recycling products that contain lead, such as car batteries and other electronic devices) has increased. There is no complete account available of current and historical secondary lead smelting sites in the United States. One EPA estimate indicates that more than 90,000 people experience elevated threats from 15 secondary lead smelters located in 10 states.

The solution: Lead in the air and soil can be reduced through prohibition of leaded airplane fuel, the reduction of air emissions from secondary lead smelters, increased public funding for cleanup of contaminated sites, and prioritization of industrial site cleanup.

How government and communities are addressing lead contamination in the air and soil

The EPA tracks the presence of hazardous substances like lead at certain locations through an inventory of places known as Superfund sites. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) requires the identification of a principal responsible party (e.g., the smelter or mine that occupied the site) that caused the contamination and provides steps to reduce related hazards.

The EPA has documented lead contamination at 66 percent of the 1,300 Superfund sites it has examined across the country. In 2016, the agency found that 800,000 children under age 18 reside, roughly, within one mile of active Superfund sites.

While CERCLA initially funded the cleanup of these sites through a tax on crude oil, imported petroleum products, and hazardous chemicals, this provision expired in 1996, leaving the EPA with severely reduced resources for site cleanup.

The Omaha, Nebraska city council requested assistance from the EPA after blood tests revealed that nearly 10 percent of tested children in Douglas County, which contains Omaha, had high blood lead levels. After investigating contamination from historic smelting and refining operations, the EPA identified approximately 14 square miles of property in East Omaha as being at high risk, and initiated cleanup of those locations. The EPA has tested nearly 40,000 area properties and cleaned up more than 12,000 that were polluted with lead.

Children can be exposed to lead through certain consumer goods

While lead-based paint, water, and industrial sources are the major sources of lead exposure, lead is still used in a variety of everyday products, including candies, cosmetics, and spices.

According to one study through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), imported candy contributes 10 percent of dietary lead for children ages 2 to 6.

Greta, a homeopathic health remedy used to treat upset stomach, contains high levels of lead.

Tiro, an African eye cosmetic, has been found to contain 82 percent lead, according to the FDA.

Lead compounds used in pottery glazes can leach into food if the product is fired at inadequate or uncontrolled temperatures.

Children of color are more at risk of being exposed to lead

In 2016, approximately 500,000 children ages 1 to 5 had blood lead levels at or above 5 micrograms per deciliter, according to the CDC. However, no level of lead in the blood is considered safe: hundreds of thousands of additional children who may have blood lead levels lower than 5 micrograms per deciliter are also at risk of cognitive and developmental delays that can result from lead exposure. Research finds that even low levels of lead in the blood—between 3 and 5 micrograms per deciliter—can damage the brain, leading to impaired memory and executive functioning skills.

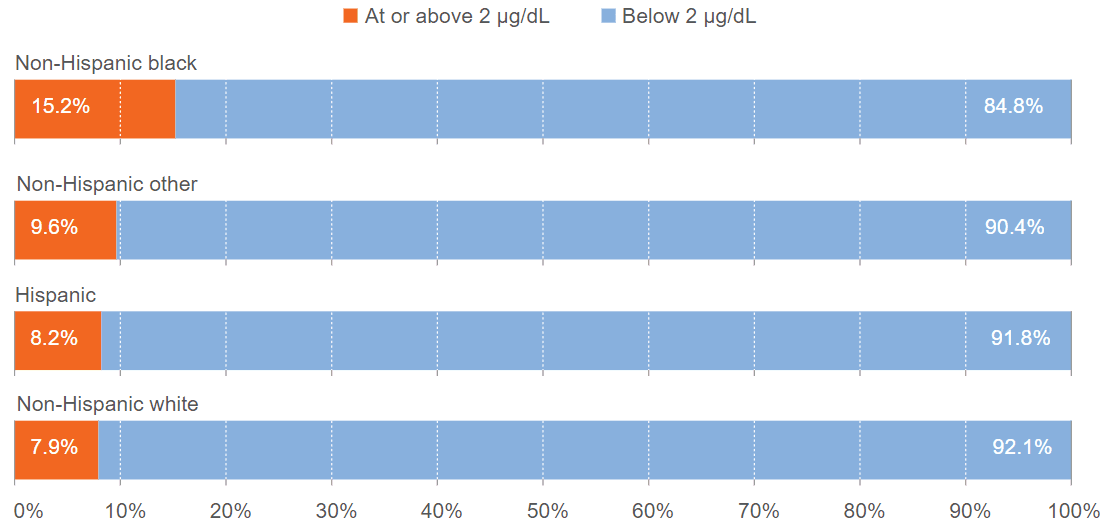

While any child can be affected by lead, children of color are more at risk. Research from Harvard University has found that black children have average blood lead levels well above those of non-Hispanic white and Mexican-American children.

Black children are more likely to have higher blood lead levels

Share of children ages 1 to 5 with blood lead levels below and above 2 µg/dL by race and ethnicity, 2011–2014

Source: Altarum analysis of National Center for Health Statistics, “National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012,” accessed May 26, 2017, link; and National Center for Health Statistics, “National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2014,” accessed May 26, 2017, link

Communities of color are more likely to live in older housing with lead paint hazards, a reality with origins in unfair lending practices and social policies such as redlining. In housing, redlining is the practice of denying mortgages and financial services to people in neighborhoods based on racial or ethnic composition, with no regard for residents’ actual qualifications. One national survey found that 28 percent of African American households and 29 percent of low-income households face housing-related lead hazards, compared with 20 percent of white and 18 percent of more affluent households.

The disproportionate risk of lead exposure for communities of color has serious implications for the possibility of achieving health equity in the United States.

The United States lags other countries in reducing the sources of lead exposure for children

Although federal agencies, states, and communities have imposed restrictions on lead over the past 40 years, the metal can still be found in many sources—primarily through drinking water and paint in older homes.

The United States lags many European countries by nearly 50 years in reducing the sources of exposure to lead. Throughout the 20th century, the U.S. Lead Industries Association aggressively promoted lead as a superior construction product and downplayed its public health risks. Lead pipes and plumbing were permitted for use in construction and houses as recently as 1986, and leaded gasoline was not phased out completely until the 1990s.

Children exposed to lead can face developmental and learning deficits

Even very low levels of lead exposure can have lasting negative effects on children. Lead affects children in particular because it mimics other essential metals that are absorbed by the brain in childhood (e.g., calcium, zinc, iron, and copper). A child’s cognitive functions are strongly affected by lead, which can result in behavioral, academic, and economic issues later in life.

Lead exposure can lead to:

- Impaired memory

- Impaired executive functioning skills, including working memory and self-control

- Decreased IQ

- Hyperactivity, impulsivity, and other attention issues, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Delays in development of language skills

Because of these cognitive effects, children who have lead poisoning are more likely to:

- Be diagnosed with a learning disability

- Struggle in school or drop out altogether

- Engage in risky behaviors like drug and alcohol use

- Get into trouble with the law

- Struggle at work

- Earn less money

These challenges are similar to those faced by children who have experienced trauma or poverty. This means that the same programs that help these children—high-quality academic and behavioral interventions—are likely to help children who have been exposed to lead.

Policymakers can protect future generations of children from lead

Policymakers can have a big effect on children’s lives by taking steps to protect future generations from exposure to lead. Preventing blood lead levels among children born in 2018 from rising above zero would generate billions of dollars in benefits for the United States.

There are a number of ways to protect hundreds of thousands of children from lead exposure:

- Removing leaded drinking water service lines from the homes of children born in 2018 would protect more than 350,000 children and yield $2.7 billion in future benefits.

- Eradicating lead paint hazards from older homes occupied by low-income families with children would protect more than 311,000 children.

- Ensuring that contractors comply with the Environmental Protection Agency’s rule requiring lead-safe renovation, repair, and painting practices would protect about 211,000 children born in 2018.

- Eliminating lead from airplane fuel would protect more than 226,000 children born in 2018.

Children who have been exposed to lead can benefit from high-quality academic and behavioral interventions

While it is critical that we strive to ensure that no children are exposed to lead in the future, we must also help those children who have already been exposed. If children with previous exposure to lead do not receive appropriate early interventions, lead-related deficits can ripple through their entire lives.

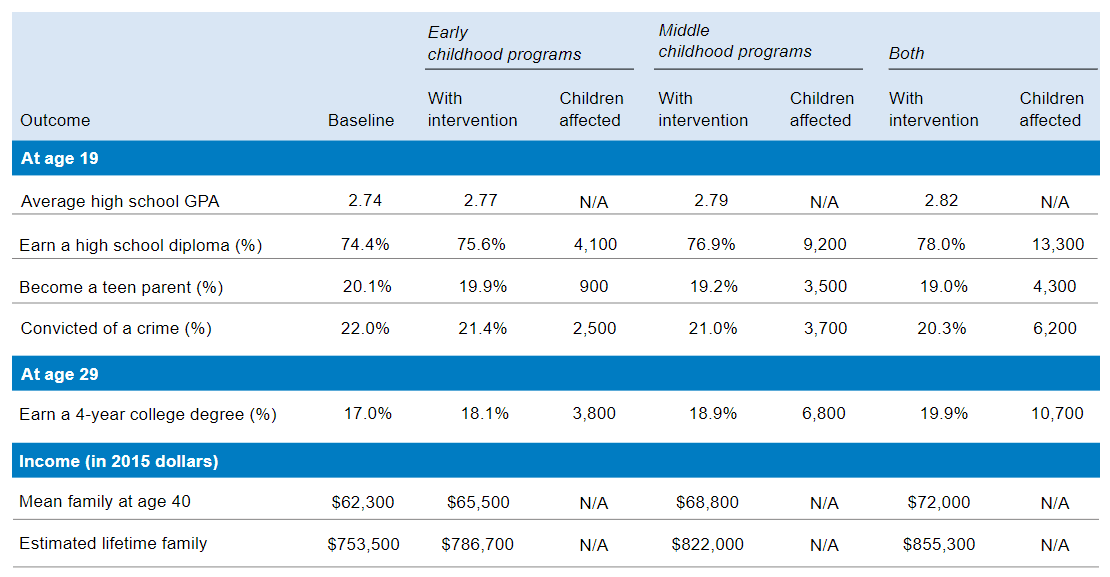

A Child Trends and Urban Institute analysis of more than 8,000 children using the Social Genome Model—which examines how interventions at different life stages affect a person’s life—suggests that high-quality interventions in childhood could yield benefits for children who have been exposed to lead. Lead-exposed children who receive such interventions could have higher GPAs, be more likely to earn a high school diploma, be less likely to become a teen parent or be convicted of a crime, and have higher earnings later in life.

Children exposed to lead could benefit from high-quality interventions in childhood: These interventions could increase lifetime earnings as much as $100,000

Effects of early and middle childhood interventions on education, crime, and income

Notes: Analysis is based on the Social Genome Model’s sample of about 8,000 children, drawn from the Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth dataset. To arrive at the number of children positively affected, the research team applied the percentage point differences between baseline conditions and total prevention to the roughly 365,000 children in the 2018 birth cohort whose blood lead levels would probably exceed 2 micrograms deciliter.

Source: Social Genome Model analysis by Child Trends and the Urban Institute

1. Improve blood lead testing

The first step in identifying children exposed to lead and making sure that they receive the necessary support is to determine the level of lead in their bodies. A blood test is the preferred method for determining exposure.

Currently, some state health departments rely on risk factor screening questionnaires to identify children at a high risk of lead exposure. These questionnaires ask about housing and other living conditions, but one study found that many poorly predict the actual risk of lead exposure.

While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (part of the Department of Health and Human Services) requires that all children who receive Medicaid be tested for various health indicators at 12 and 24 months of age—including a blood lead test—a Reuters investigation found that about 40 percent of Medicaid-enrolled children do not receive these tests.

According to the Reuters report, this happens for a variety of reasons, including insufficient awareness of testing requirements among doctors or children who miss appointments. As a result, these children miss a vital opportunity to be screened for lead exposure.

2. Provide children with academic and behavioral intervention

Many lead-poisoned children have learning and developmental deficits that are similar to those seen in children affected by trauma and poverty. Within this broader population, evidence-based programs have demonstrated positive effects on important outcomes such as academic achievement and executive functioning. Investments in high-quality child development interventions could reap positive benefits for children who have been exposed to lead.

Because the deficits associated with lead often do not become apparent until a child is older, it is best to begin intervention as early as possible.

Only rigorously tested, culturally competent, high-quality interventions are likely to deliver benefits for any children, including those who are exposed to lead. The following are examples of programs that have demonstrated the positive effects of high-quality childhood interventions among children with some of the same deficits faced by lead-exposed children:

- Nurse-Family Partnership connects young, low-income, first-time expectant mothers with a public health nurse who meets with women in their homes from pregnancy until the baby turns 2.

- The Incredible Years promotes positive parenting and teaching practices, interpersonal skills, academic competence, and general social skills. It has been shown to decrease harsh disciplinary practices, improve parenting skills, and enhance children’s academic and social competence.

- Steps to Respect is a school-based bullying prevention program that focuses on prosocial beliefs and social-emotional learning. Participating students demonstrated fewer antisocial characteristics and schools saw a nearly 25 percent reduction in bullying behavior.

3. Support programs that improve child nutrition

Nutritional interventions can support children’s development in areas for which lead exposure is known to cause impairment—particularly reading, math, and social-emotional skills—and may serve as a buffer against its negative effects.

In North Carolina, children with high blood lead levels received various health- and nutrition-related services, and parents were given advice about reducing lead in the home. Children who received these services saw improved educational achievement and reduced adolescent antisocial behavior, relative to children who had temporarily elevated blood lead levels and did not receive such services.

Michigan State University has introduced a nutrition-based approach to lead exposure by educating the public on the role of nutrition in child development, as part of the university’s Pediatric Public Health Initiative created in response to Flint’s lead crisis.

Next steps to protect children from lead

Eliminating lead exposure will avoid health and financial harm to families and future generations, and could yield as much as $84 billion in benefits before accounting for the costs to achieve such prevention.

To eliminate lead exposure, we need strategies that take a comprehensive approach to reduction. Priorities include:

- Reducing lead in drinking water in homes built before 1986 and in other places where children spend time, including schools and child care facilities

- Removing lead paint hazards from low-income housing built before 1960, and in other places where children spend time

- Reducing lead in food and consumer products

- Reducing air lead emissions

- Cleaning lead-contaminated soil, especially around homes, schools, and child care settings

Acknowledgements

The information in this interactive is drawn from 10 Policies to Prevent and Respond to Childhood Lead Exposure, a product of the Health Impact Project, which is a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts. Child Trends contributed to the report, along with researchers from the Altarum Institute and the Urban Institute.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram