Updated 8/4/2023: We have edited the legend of Map “ECIDS Development Described in 2022 PDG B-5 Applications” (Figure 1) on page 4 and the rows in Appendix A Table 2 “ECIDS Development Described in 2022 PDG B-5 Applications” on pages 14-15 to clarify that states’ ECIDS status is displayed only for their PDG application narratives. The text in these locations previously read “No ECIDS” but now reads “No ECIDS Discussed.”

Comprehensive, coordinated data can help policymakers answer critical questions about equitable access to early childhood programs, workforce development needs, or school readiness. However, these data are not always accessible or integrated in ways that give policymakers the whole story of children’s experiences during the early years. In fact, early childhood data in most states are fragmented and uncoordinated, are often housed in multiple systems, and are managed by different state and federal agencies. For example, data on children’s participation in early learning programs may be housed in a different data system than data about children’s development prior to starting kindergarten. As a result, policymakers may be unable to answer questions about how children’s early experiences do or do not support their later development and may have limited data to inform the improvement of services and systems that serve children from birth to school entry. By bringing together this siloed information—in other words, by integrating these data—data systems can give policymakers a more comprehensive understanding of programs’ accessibility and the degree to which they are achieving their goals.

Spurred by federal investments, the past decade has seen progress in data integration and data system development that has allowed states to begin to address these critical policy questions. Multiple rounds of Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge (2011, 2012, 2013) and Preschool Development Grants (2014, 2018, 2019, 2022) created opportunities to examine longitudinal trends to assess whether early care and education (ECE) policies are leading to greater equity and improved program quality.

About this brief

Through our analysis of states’ applications for Preschool Development Grant funding, we examine and uplift the ways in which state leaders are using the latest round of Preschool Development Grant funding to address data integration needs and advance the use of early childhood data to guide early childhood policies and practices.

Of particular interest are states’ efforts to develop early childhood integrated data systems (ECIDS), as well as coordinated service eligibility and applications systems. An ECIDS coordinates information about program participation, child care supply, and workforce characteristics from multiple data systems. When combined, these data can be used to help policymakers, practitioners, and researchers understand which families have access to programs, where there are service and workforce gaps, how children fare later in their educational trajectories, and what programs best meet the needs of children and families. Note that this analysis is not a comprehensive scan of the national scope of early childhood data integration, but rather a scan of those efforts funded through the 2022 round of PDG B-5 grants.

The brief first provides an overview of these grants, the data integration activities they fund, and the methodology used for this analysis. The next section summarizes states’ reported use of PDG funds to plan, implement, or expand early childhood data integration.

Download

About the Early Childhood Data Collaborative (ECDC)

Since 2009, ECDC has committed to promoting policies and practices that support the development and use of state coordinated early childhood data systems to improve the quality of early learning programs and the workforce, increase access to high-quality care, and, ultimately, improve child outcomes. These data systems are a critical tool for policymakers to know who is receiving services and where there are service gaps. Having comprehensive data helps policymakers and state decision makers support full access to high-quality early care and education for all children.

Overview of Preschool Development B-5 Grants

The Preschool Development Grant Birth to Five Program (PDG B-5) aims to support state efforts in coordinating early childhood services for children from birth to age 5. States can support this coordination through analysis of data that are often collected and stored in separate data systems. Efforts to coordinate services across existing early childhood programs can potentially provide impetus for integration of early childhood data to learn about populations served and to inform policy decisions regarding service delivery models.

In 2022, states and U.S. territories had the option to apply for one of two grant opportunities from the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A total of 42 states were awarded PDG B-5 grants.

- Twenty-one (21) states received one-year planning grants, which were made available to the four states that had not previously received a PDG Birth through five (B-5) award and to 23 states that were prior renewal grant recipients in the previous (third) year of renewal funding.

- An additional 21 states received three-year renewal grants, which were available to states to build upon work completed through an initial PDG grant.

Appendix A (found in the PDF) details the types of Preschool Development Grants awarded to states and territories during each round of application solicitation from 2014 to 2022.

In the 2022 round of funding, planning grants required applicants to discuss their use of PDG funds to support work in five specified activity areas:

- Updating comprehensive statewide B-5 needs assessment

- Developing or updating comprehensive statewide B-5 strategic plan

- Maximizing parent and family engagement in the B-5 system

- Supporting the B-5 workforce and disseminating best practices

- Supporting program quality improvement

Renewal grant applications included an additional activity—subgrants to enhance quality and expand access to existing and new programs. Renewal grant applications also provided states the option to use PDG funds to undertake activities in bonus areas. Completion of any of the three bonus areas (coordinated application, eligibility, and enrollment; improving workforce compensation; and increasing access to inclusive settings) provides an opportunity for applicants undertaking work in these areas to receive bonus points toward their PDG B-5 application score. Activities and bonus areas for both types of grants are detailed in Appendix B (found in the PDF).

The Monitoring, Data Use, Evaluation and Continuous Quality Improvement section of the PDG B-5 grant application asks applicants to express the extent to which they are able to link information about early childhood programs, including health and public benefit programs. The ability to link or integrate various sources of early childhood data can improve states’ access to the information needed for quality improvement work across the spectrum of early childhood services, including within the activities and bonus areas mentioned above.

This analysis focuses on states’ capacities to link data, their activities to support these efforts, and information they provided on the coordinated applications bonus area. The development of coordinated applications, designed to streamline access to services for families, is of interest to this analysis because data collected through these systems may be incorporated into programmatic data for programs whose data are potentially included in early childhood integrated data systems.

Methodology

To identify planned uses of funds related to data systems integration and a coordinated eligibility system, the study team scanned all awarded grant applications (21 planning and 21 renewal grant applications) for terms associated with data integration, coordinated eligibility and application systems, and other topics of interest. Key search terms were identified by analyzing a sample of PDG applications for common terms used by applicants in the application narratives to discuss early childhood data integration. The relevant search terms identified through this process were: application, central, coordinate, coordination, data, data sharing, data system, ECIDS, eligibility, enrollment, fragment, governance, identifiers, identification, IDs, integrate, link/linkages, registry, and workforce. Once passages describing topics of interest were identified, the relevant text was extracted and cataloged. A coding scheme was developed to classify the relevant text for ease of analysis.

Early childhood data integration can employ multiple processes or methods, from strategic planning to development and expansion, that can be implemented consecutively or concurrently. To capture the breadth of early childhood data integration activities described in PDG applications, the following two areas of interest for analysis were identified:

- ECIDS status: The status of a state’s early childhood data coordination/linkage efforts, including use of unique identifiers, unique identifier development method, data governance, and staffing.

- ECIDS linkages: Whether a state/territory links or plans to link information to its early childhood data system from state longitudinal data systems, workforce data systems, or coordinated eligibility and application systems.

We also examined how states plan to use these data to better understand what activities or policy questions are informed by integrated early childhood data.

Summary of Findings

Examining ECIDS development status for PDG B-5 awardees provides a broader picture of the national scope of early childhood integration and how these efforts align with application priorities around data linkages and integration. With this in mind, we organized the results of this analysis by the key areas of interest investigated: ECIDS development status and linkages between ECIDS and other data systems. The key themes below were gleaned from states’ PDG B-5 applications.

79 percent of PDG B-5 awardees discussed ECIDS activities.

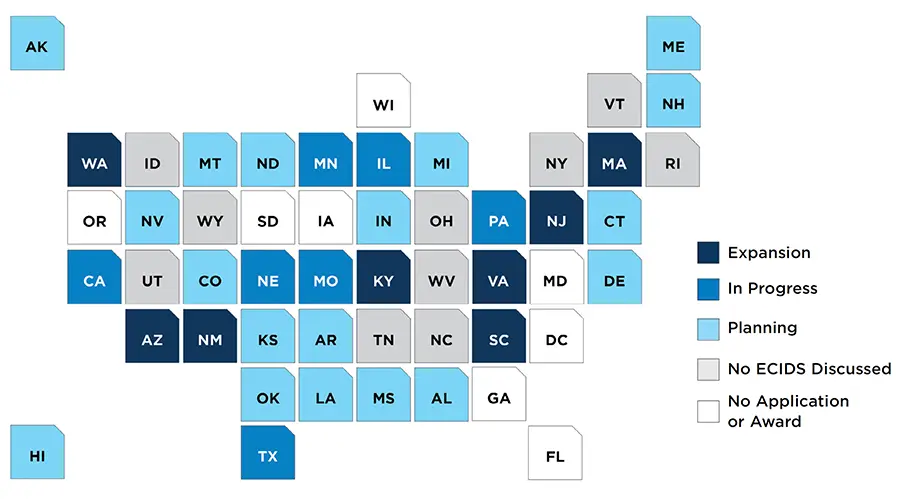

Identifying states with currently operational ECIDS does not fully capture the scope of early childhood integration efforts happening across the country. As such, we analyzed information from the PDG B-5 grant applications for all types of activities related to the development of ECIDS. Our reviews found that 33 of 42 applications discussed ECIDS activities to support states’ data integrations efforts that were in different stages of development. We assigned an ECIDS development status to each state using the following phases of development (see Figure 1):

- Planning: State/territory is engaged in strategic planning activities, mapping, or design of early childhood data integration/linkage.

- In progress: State/territory has a plan or recommendation they are currently implementing through the PDG grant.

- Expansion: State/territory is in the process of linking early childhood data in a centralized place that can be accessed to use and inform programmatic and policy efforts or to integrate information from additional early childhood programs.

Figure 1. ECIDS Development Described in 2022 PDG B-5 Applications*

*Data for this figure are available in Appendix A (found in the PDF).

Of the 42 states that submitted applications for PDG B-5 funding in 2022, 43 percent (18 states) were in the planning phase of ECIDS development as of the date of PDG application submissions. Seventeen percent (7 states) were in progress on developing ECIDS and 19 percent (8 states) were expanding already existing ECIDS. Twenty-one percent (9 states) did not discuss information about ECIDS development in their applications, although some may be supporting ECIDS work through previous PDG B-5 grants or other sources of funding. Of those states whose applications don’t address ECIDS work funded by PDG B-5, three states’ applications—Ohio, Rhode Island, and Colorado—discussed actively linking early childhood data through a different process.

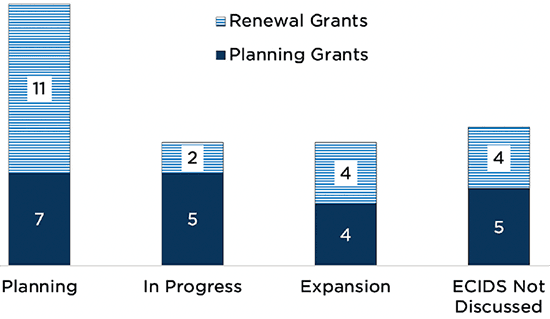

Figure 2. ECIDS Development Status Discussed in 2022 PDG B-5 Applications by Grant Type

The distribution of states at each phase of ECIDS development differed between states that received planning grants and those that received renewal grants (see Figure 2). A higher proportion of awardees for planning grants have an existing ECIDS or are in the expansion phase, whereas a higher proportion of renewal grant awardees are in the planning phase of ECIDS development. Forty-eight percent of planning grant awardees have an existing ECIDS or are in the process of expanding an existing ECIDS, compared to 29 percent of renewal grant awardees. Among states in the planning phase, there is variation in activities undertaken by awardees. Arkansas, for example, is planning to enhance its state longitudinal data system (SLDS) to include early childhood program data. Oklahoma convened a work group, completed an ECIDS and data governance plan, and will continue developing an ECIDS that was previously incomplete due to lack of funding. Hawaii is determining the feasibility of either expanding its SLDS to include early childhood data or building a new ECIDS.

State spotlight: Colorado

Colorado is in the planning phase of ECIDS development. Although Colorado does not currently have an ECIDS, its data on vital records, Medicaid, child welfare, IDEA Part B and Part C, child care subsidies, early childhood workforce, TANF, SNAP, juvenile justice services, WIC, workforce training programs, and W-2s can be linked through a state data initiative called the Linked Information Network of Colorado (LINC). The LINC initiative is also engaging with additional state data partners. Colorado has a robust early childhood workforce data collection system that generates a public-facing early care and education workforce data dashboard, which includes information on workforce demographics, educational attainment, and qualifications, and produces a ratio of children to early care and education professionals by county or region.

60 percent of states are working on an ECIDS plan to link them with other data systems.

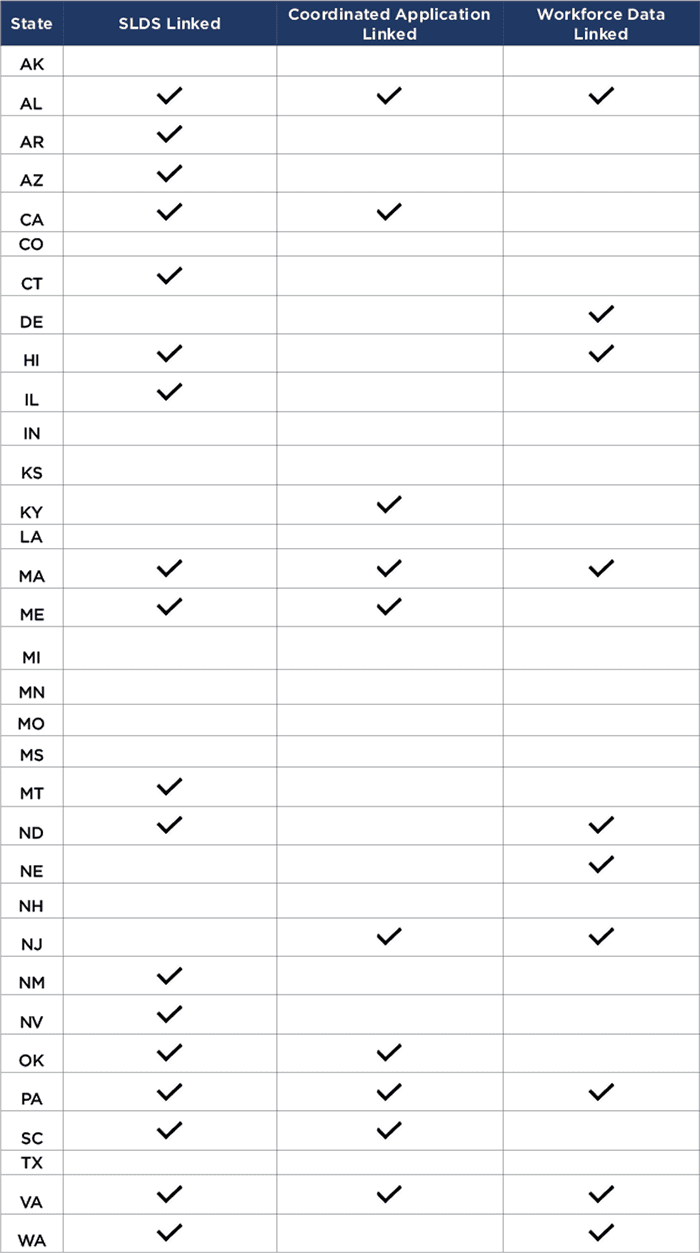

The linkage of early childhood data with other data systems allows information about children’s, families’, and workforce members’ needs to be used jointly with information on their use of other social supports to understand their educational and professional trajectories. Our analysis included reviewing whether and how state ECIDS development is being linked with SLDS; with coordinated application, eligibility, and enrollment (bonus area 1 of renewal applications); and with workforce data systems. Twenty of the 33 states (60%) that discussed ECIDS in their applications mentioned plans to link ECIDS with other data systems. Often, these data systems are housed in different agencies that may or may not be linked with the state ECIDS efforts. Data linkages between ECIDS and these external data systems can help states gain a better understanding of the early childhood landscape. Table 1 below shows which of the 33 states that discussed an existing or planned ECIDS in their 2022 PDG B-5 application are currently linking or planning to link information with coordinated application, SLDS, and workforce data collections.

Several states noted that data linkages were conducted or planned through a previous round of PDG grant award or through another funding source. Four states (Alabama, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia) link or plan to link ECIDS data to all three previously mentioned data systems. Linking ECIDS to these three data sources can provide rich information to help states learn about families and children over time, support the workforce that serves them, and develop policies that enhance program quality and access.

Table 1. ECIDS data linkages to other data systems, by state*

SLDS linkages

Over half of applicant states (18 states) that discussed already having, or planning for, an ECIDS (33 states) also discussed plans to link data from ECIDS with their SLDS. Linking early childhood data with SLDS helps answer questions about the best way to support children’s development prior to and after school entry to set them on a path toward better economic and health outcomes. Since 2006, over $826 million has been awarded to 55 states and U.S. territories to develop and implement longitudinal data systems spanning from early childhood through workforce entry. SLDS are typically managed through state departments of education and are used to connect education-related data over time to guide policy and funding decisions aimed at improving student learning and outcomes. Because early learning programs are administered through departments of social services (e.g., child care subsidies), departments of health (e.g., home visiting), local programs (e.g., Head Start)—in addition to departments of education (e.g., state-funded preschool)—efforts to integrate these data may require the coordination of data from multiple agencies.

State spotlight: Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Enterprise to Link Information for Children Across Networks (PELICAN) is an early childhood integrated data system that encompasses data on subsidized and non-subsidized child care, QRIS, IDEA Parts B and C, State Pre-K, TANF, SNAP, Medicaid, home visiting, and K-12. PELICAN also integrates teacher, family and program data. Pennsylvania is one of two states where ECIDS is also currently linked to SLDS, a coordinated application system and workforce registry.

Coordinated application linkages

Only one third of applicant states (10 states) that discussed having, or planning for, an ECIDS also discussed plans to link data from ECIDS with a current or planned coordinated applications system. Coordinated application processes facilitate families’ access to early childhood services by allowing families and their advocates to determine which early childhood programs they are eligible for based on their personal information and needs. Additionally, the information entered into a coordinated application can be streamlined to allow families to apply for multiple programs they may be eligible for without having to complete multiple applications for enrollment. Connecting data from coordinated applications to ECIDS can help states determine if eligible families ultimately enrolled and received services within the programs included in the ECIDS. Potentially, children can be assigned a unique identifier within the coordinated application system that can carry through to ECIDS when families enroll in programs, creating a broader picture of early childhood system access.

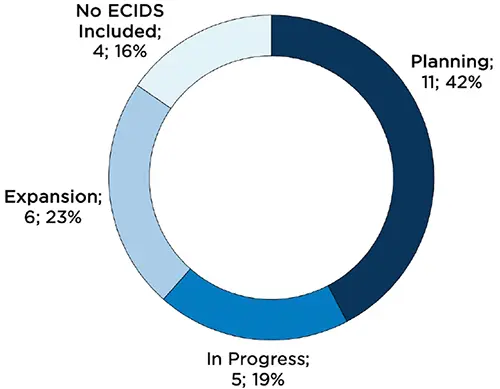

While only renewal applicants (21 states) were given bonus points for including plans for a coordinated application process in their applications, our analysis found that a total of 26 states—from both renewal (n=15) and planning (n=11) grant types—included information about an existing or planned coordinated application. Of those states, 58 percent (15 states) currently utilize some type of a coordinated application system, and 42 percent (11 states) are planning for the development of a coordinated application.

Figure 3. ECIDS Development Phase for Awardees Addressing Coordinated Applications

The 26 states that included information about coordinated application are in varying phases of ECIDS development. Of these states, 42 percent (11 states) are either expanding or continuing ECIDS work. An additional 11 states are in the planning phase of ECIDS development and four states did not include ECIDS in their PDG-B5 application.

State Spotlight: Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia has developed a series of regional networks that function as early childhood services delivery hubs. In addition to having a coordinated eligibility and application process, each regional network is staffed with a full-time employee dedicated to coordinated eligibility and enrollment. These employees also participate in a Community of Practice to improve access to early childhood services.

Workforce data linkages

Less than one third of state applicants (10 states) that discussed having, or planning for, an ECIDS also discussed plans to link workforce data as part of their ECIDS. Early childhood workforce data encompasses information about professionals who care for children across different settings. Workforce data could include, but are not limited to, information about workers’ compensation, education, and training. States may obtain this information through various data collection efforts, including workforce surveys, early childhood workforce registries, and educator credentialling and accreditation systems.

Linking data about early childhood workforces with other early childhood data gives policymakers comprehensive information about those who care for children as they grapple with policy issues related to child care supply, staff turnover, and ensuring that children with the greatest needs have consistent well-trained caregivers to support their needs. For example, Washington state plans to enhance data integration efforts to connect its workforce and training registry data (MERIT) with its quality rating and improvement system (Early Achievers), child care licensing, and other data systems used to support professional development and staff retention initiatives. Workforce data are central to supporting inclusive learning environments and providing appropriate financial and educational supports to programs working to maintain and meet quality standards.

State Spotlight: Illinois

Illinois houses both the Illinois Longitudinal Data System, which includes ECE data from eight state agencies, and the Chicago Early Childhood Integrated Data System. Additionally, Illinois has three workforce data collection systems that house data for an early childhood educator dataset. This dataset can be linked to broader educator workforce and other workforce datasets, allowing analysis and comparison of early childhood educator characteristics with information on the workforce at large.

64 percent of states discussed developing unique identifiers.

A unique identifier (UID) is a single, unduplicated number that can be assigned to a child, program, or individual; it allows for their identification within different data systems throughout their participation in various ECE programs and services. Of the 42 states that were awarded PDG B-5 funds, 64 percent (27 states) discussed using or planning to use a unique identifier to link data on individuals across programs. UIDs are an integral process in ECIDS development because they facilitate the linkage of data about families, programs, and workforce members across early childhood services. To develop unique identifiers, states may need funding to access resources such as software licenses to automatically generate unique identifiers or match children’s data across programs using unique characteristics. Funding could also help states develop UIDs by supporting existing staff or hiring new staff to develop, execute, and oversee those processes.

Several methods can be used to create unique identifiers within data systems. Some databases, data warehouses, and other types of software applications can generate a unique random identification number that is internally assigned to a person in the data system. UIDs can also be created by matching data on individuals from different data systems (i.e., first name, last name, date of birth, etc.) to identify and link data pertaining to the same person. The matching process can be done using a software application or manually. About half (13 states) of all state applicants that discussed developing UIDs specified the method by which they planned to create them. Most described using a process or software to automatically generate and assign a unique identifier for each individual and for matching process records across data systems. UIDs can help states obtain an unduplicated count of children or families utilizing early childhood services and track the receipt of those services over time.

State Spotlight: Kentucky

Kentucky’s ECIDS is administered through the Kentucky Center for Statistics (KYSTATS). KYSTATS developed a data sharing agreement with the Office of Vital Statistics, which helps Kentucky assign a unique identifier to all children in the vital records system and to track program participation from birth to 3rd grade. This allows for population-level analysis of early childhood data and program participation.

59 percent of states discussed addressing data governance.

Data governance is a process through which data ownership is established and roles and responsibilities pertaining to data collection, security, and use are defined. Data governance is best practice in data management and is of particular importance when data are shared across programs and agencies, where it provides accountability and builds trust amongst data sharing partners. Of the 42 applications we analyzed, 59 percent (25 states) discussed addressing data governance within PDG B-5 applications. While most states discussed efforts to build an early childhood data governance structure, four states have a broader data governance structure to guide the collection and use of administrative data; however, those structures don’t oversee the development or use of an ECIDS specifically.

For example, in 2010, West Virginia—a state without ECIDS—created an Early Childhood Advisory Committee (ECAC) to improve the ECCE system for children, including via data governance. States with existing ECIDS may have more established data governance processes than states in the planning phases of ECIDS development. Twelve of the 15 states (80%) that mentioned having an existing ECIDS in their PDG applications also discussed data governance. In contrast, 10 of the 18 states (56%) in the planning phase of ECIDS development addressed data governance in their applications.

Dedicating a staff member to data governance structures and processes can be beneficial, especially when early childhood data are distributed across agencies and programs. We reviewed the Organizational Capacity and Budget sections of the PDG B-5 applications to learn which applicants mentioned having designated staff that support data integration or data governance. Of the 25 states that addressed data governance in their applications, 17 mentioned having or planning to hire designated data integration or data governance staff.

Most states planned to use ECIDS for an unduplicated count of children served and to improve program quality.

The integration of early childhood data can serve many purposes depending on each state’s priorities. The most commonly reported uses of integrated early childhood data addressed in PDG applications were to obtain an unduplicated count of children served in early childhood programs and to answer policy questions about early childhood programs (i.e., service delivery planning and analysis, program evaluation, etc.). Of the 33 applicants that have or plan to develop an ECIDS, 91 percent (30 states) discussed using ECIDS data to obtain unduplicated counts of children served and 88 percent (29 states) discussed using ECIDS data to obtain program information to support evaluation and quality improvement. Additional uses of integrated early childhood data include completing and/or updating needs assessments and strategic plans, answering policy questions about the early childhood workforce, and developing public-facing dashboards. For example, Kentucky uses its ECIDS to develop county-level early childhood profiles that include early care and education availability.

States noted that funding, the impacts of COVID-19, and a lack of support were barriers to ECIDS development.

While many states discussed the benefits of integrating early childhood data, along with their planned uses of the PDG B-5 funds, some also noted challenges they encountered while trying to develop an ECIDS. The most common challenges described by applicants were lack of funding, the impacts of the COVID 19 pandemic, and a lack of support from agencies or state administration. Hawaii discussed a need to shift priorities to meet the immediate needs of families and the early childhood workforce during the COVID 19 pandemic. Idaho’s application mentioned challenges in obtaining support for data sharing at the local and state levels. Oklahoma’s application discussed both a lack of funding and variation in early childhood data collection standards and practices as causes of delay in developing its ECIDS.

Conclusion

The PDG B-5 funding is helping states improve their use of early childhood data. While not an explicit focus of the PDG B-5 grants, a large number of states (79%) plan to use funding to support activities to implement or expand an ECIDS. These plans include linkages with other data systems like SLDS, coordinated applications, or workforce data systems (60%) to help leaders understand children’s transitions into kindergarten and to ensure that children are connected with early learning professionals and services that support their needs. The development of unique identifiers (64%) and data governance structures (59%) were specific areas of development noted in the applications. Most states planned to use their ECIDS to obtain an accurate count of children served across early learning programs and to improve program quality via accurate data to evaluate early learning initiatives.

Funding opportunities like the PDG B-5 grants offer a unique opportunity for states to design and implement data systems that can better help policymakers answer critical questions about equitable access to early childhood programs, workforce development needs, or school readiness. Moving forward, the Early Childhood Data Collaborative plans to assess how funds are helping to propel the development of ECIDS through case studies and surveys of states’ systems. For more information about early childhood data integration efforts, you can go to our website at www.ecedata.org.

Suggested citation

Hackett, S.E., & King, C. (2023). States’ Preschool Development Grant applications reveal priorities for stronger data integration. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/4224m6501x

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram