State Policymakers Can Support Equitable School-based Telemental Health Services

At least half of all people with mental health disorders began showing symptoms in childhood, and the earlier treatment can start, the better. Despite this context, most communities in the United States lack access to child mental health services. To increase access to mental health services in the COVID-19 pandemic, many states and school systems implemented telemental health services (TMH)—that is, mental health services provided either through video conferences or over the phone. TMH services can be a powerful tool to increase access to mental health services, including for children, but state policies can either hinder or support telemental health delivery to students.

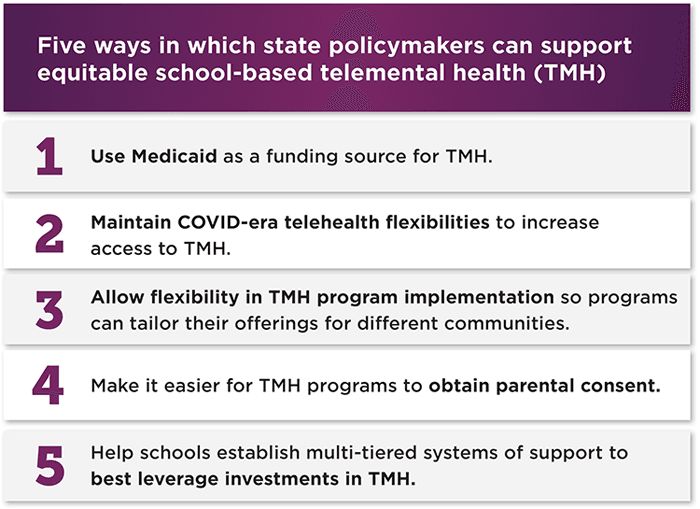

This brief presents five ways in which state policymakers can support equitable school-based TMH, with recommendations based on relevant policy context, existing research, and—in some cases—feedback from our interviews with five TMH providers who testified to on-the-ground experience with these interventions. We interviewed TMH providers in Oregon, North Dakota, South Dakota, Colorado, and Texas, all of whom were identified by the School-Based Health Alliance (check out their school-based telehealth playbook) and the Healthy Schools Campaign.

1. Use Medicaid as a funding source for telemental health.

School Medicaid programs can provide funding for TMH services in two ways. First, states can expand their school Medicaid programs to cover services outside of special education. Although states have had the opportunity to make this change since 2014, over half of them are not leveraging this potential funding source. Second, states can recognize schools as sites for TMH service provision, which is relevant for states that have not expanded their school Medicaid programs. For 14 states, this flexibility may end when the public health emergency does—possibly as soon as April 2022.

Depending on what is included in their State Medicaid Plan, states may be able to expand their school Medicaid programs or recognize schools as TMH sites via updated state guidance or legislative change, while others may need a State Plan Amendment. Data from state, district, and school personnel reveal the complexities of obtaining Medicaid reimbursement, including the paperwork and administrative burden and licensure differences between education and health providers. States can ease some of these burdens by aligning the credentialing for mental health providers between the education and health sectors. Some programs we interviewed emphasized the value of seeking diversified funding streams beyond insurance reimbursement: Programs with more than one stream often had the flexibility to scale TMH services quickly, reimburse school staff for their time supporting TMH, provide care at no cost, and provide additional services to students when needed.

2. Maintain COVID-era telehealth flexibilities to increase access to telemental health.

Many of the flexibilities that supported the growth in TMH services during the pandemic will end with the public health emergency. COVID-era telehealth flexibilities include allowances for out-of-state TMH providers to practice, the ability for patients to receive services at home, support for a wider array of HIPAA-compliant platforms (e.g., phones, Zoom), permission for initial visits to be online rather than in-person, and payment parity between in-person and online services. Research indicates that no-show rates for child mental health appointments decreased substantially when TMH was an option, and kids’ mental health symptoms improved. Additionally, TMH flexibilities can help overcome challenges associated with insufficient supply of mental health professionals. Currently, not enough mental health professionals are available to work with children and youth, especially in rural areas. Nearly every TMH program with which we spoke credited equitable access to broadband internet as a foundational component to reaping the benefits of TMH services. Many states are trying to increase student connectivity to broadband at school and/or at home.

3. Allow flexibility in telemental health program implementation so programs can tailor their offerings for different communities.

There are well-documented disparities in access to and utilization of mental health services among youth of color, LGBTQ youth, and youth living in rural communities. As a result, many programs we interviewed tailor their implementation and community engagement efforts to the groups they serve. One program in Oregon funds a community outreach position, provided food services early in the pandemic, and conducts Zoom presentations in Spanish—allowing referrals to come to them via word of mouth in Spanish-speaking communities. Another program, in Texas, meets with rural organizations in-person to accommodate the community’s preferences and to increase trust between the program and the community it serves. Finally, one provider we interviewed made a concerted effort to recruit youth to their program’s advisory board and regularly consult with them to identify strategies to better tailor programmatic outreach efforts. Efforts to assess community needs, strengths, and preferences require staff time and resources. State officials could utilize American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ARP ESSER) funding to test the effectiveness of different community engagement methods; once ESSER funding ends, states could consolidate their efforts and funding around the most effective community engagement methods.

4. Make it easier for telemental health programs to obtain parental consent.

School-based TMH providers must obtain parental consent before providing services to students. However, getting signed consent forms from parents and caregivers has long been a stumbling block for school-based health service providers. Telehealth consent policies vary widely across states, and obtaining high response rates takes time and effort from staff and still often misses the students most in need of services. Additionally, consent forms can be long and written at a high reading level, which can reinforce language barriers, and the information requested can raise privacy concerns for parents around their immigration status. One provider from Texas realized that some parents were worried about signing a consent form because of their immigration status, so the provider created a more plain-language form that clarified that families would not be billed or have their immigration status collected. Furthermore, the program adopted an online consent option to address problems with receiving signed consent forms. Staff from a program in Colorado shared similar concerns and noted that they were ultimately granted permission to collect verbal—rather than written—consent from parents. Colorado also does not require parental consent for mental health therapy if children are older than 12, or for mental health medications if children are older than 15. Program staff found this practice helpful for broadening access to care.

5. Help schools establish multi-tiered systems of support to best leverage investments in telemental health.

Students’ mental health is best supported with a range of services, including services that support all students’ social-emotional well-being, build skills for students in need of additional supports, and provide individualized treatment for students with diagnosable mental health conditions. For example, students who receive TMH treatment will likely experience more benefits if their school also provides a supportive environment through universal social and emotional learning opportunities. Further, students may be more likely to receive TMH services if school staff are trained on recognizing mental health challenges among students.

This range of complementary services is provided under a multi-tiered system of supports, or MTSS. Recent guidance from the U.S. Department of Education highlights the value of using an MTSS to organize school mental health supports to address different levels of need, including universal promotion and prevention (Tier 1), early intervention (Tier 2), and treatment services (Tier 3). Under an MTSS, TMH services are generally classified as Tier 3, although brief TMH interventions that seek to assess need, build skills, and refer students out for more intensive needs may be classified as early intervention (Tier 2). Tier 1 services, designed to benefit the whole student body, are best offered in-person with TMH as a supplement. In the absence of comprehensive school health efforts that address both environmental factors and individual behaviors, TMH services alone may prove insufficient to address students’ mental health needs.

An MTSS can help ensure that TMH providers are not practicing in a silo, but are connected to the whole school community. TMH providers we interviewed stressed the importance of training school staff to identify student mental health needs and understand how to make a timely referral. They also felt that schools must be equipped to provide in-person crisis support in an emergency, such as when a student is actively considering harming themselves or someone else. Providers also considered it important that TMH providers themselves are connected with school and community resources, especially to support students with more acute needs. States can support schools by creating a repository of evidence-based implementation resources for MTSS, calling on schools to establish and update comprehensive school mental health plans, and funding innovative TMH integration projects to learn what works best. For example, as part of its Project AWARE grant, South Dakota created a guide for school districts considering adding telemental health services to their tiered system of supports; Washington recently passed legislation that requires school districts to develop, and annually update, a comprehensive school counseling plan.

Related Research

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth can help connect home visiting services to families

- Schools Can Reduce Barriers to Mental Health Access by Ensuring That Services Are Supportive of LGBTQ Youth

- A National Agenda for Children’s Mental Health

- Anti-LGBTQ Policy Proposals Can Harm Youth Mental Health

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram