In every state, policymakers and early childhood program leaders are grappling with how to recruit and retain an early childhood workforce that is prepared to support young children’s development while also providing this workforce the work conditions (including compensation, benefits, and ongoing professional development) that promote their own well-being. Well-trained and well-supported early childhood educators can make high-quality early care and education (ECE) more accessible for families, which, in turn, supports parents’ workforce participation and children’s school and life success.

For decades, the highest-quality training for early childhood educators has incorporated a framework known as developmentally appropriate practice (DAP), which includes training on early childhood development, appropriate child assessment, and provision of individualized educational supports for children’s learning and development. In this brief, we first provide an overview of the origins of developmentally appropriate practice and fully define the framework and its role in early care and education settings. We then discuss four research-based facts about developmentally appropriate practice that may be helpful as policymakers strive to provide the early childhood workforce with the tools they need to support young children.

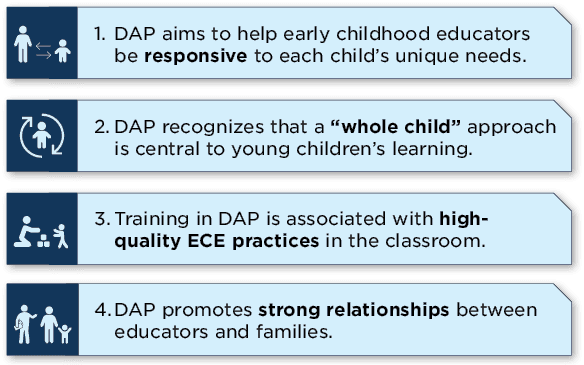

Four Ways DAP Helps the ECE Workforce Support Child Development

The Origins of the DAP Framework and Its Role in Early Care and Education

Developmentally appropriate practice, or DAP, is a framework that is grounded in developmental science research and theory. For almost 40 years, DAP has been considered the gold standard for practitioners in the field of early care and education (ECE).

The research basis for developmentally appropriate practice

For nearly 100 years, developmental scientists have studied the ways in which early experiences and interactions with caring adults contribute to how young children learn and develop. Developmental scientists have outlined theories and conducted rigorous studies to affirm that experiences in early life influence the architecture of young children’s brains; this, in turn, can influence the course of their cognitive, linguistic, social, and emotional development, especially within the first three years of life but also throughout early childhood and into adulthood. Developmental theory and research also assert that even broader contexts—such as systems, societal norms, and policies—can affect how individuals develop over time, in addition to the more immediate environments and interactions that children experience. Furthermore, developmental science indicates that children advance their knowledge and skills best through interactions with caring parents and early childhood educators who “gently stretch” their current knowledge and abilities. Collectively, these concepts and practices, based on long-standing developmental science research, provide the basis for developmentally appropriate practice as taught to and enacted by ECE educators.

Defining DAP and its use in ECE settings

Developmentally appropriate practice is defined as activities or approaches—designed by and for early childhood educators—that are well-suited to the developmental stage, ability level, and individual needs of children and that aim to support the success of all children in ECE settings.

Developmentally appropriate practices are ECE activities/approaches tailored to the developmental stage, abilities, and needs of all young children across ECE settings.

In 1987, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), a professional membership organization for early childhood educators, developed a DAP Guidebook for early childhood educators that defined DAP, shared research findings supporting DAP, and provided concrete examples of DAP in action in ECE settings. Over the years, this DAP Guidebook has been updated to incorporate new research findings and provide more concrete examples of how to apply DAP in classrooms, but the basic tenets of DAP have remained the same over time.

DAP focuses on intentional educator practice and decision making within an ECE setting. Specifically, early childhood educators who apply DAP base their practices and decisions on three things:

1. Knowledge of child development: Early childhood educators apply theories and research on children’s physical, cognitive, linguistic, and social-emotional development.

2. Each child’s identified strengths and needs: Early childhood educators observe each child’s behavior within a natural setting to determine their abilities across multiple developmental domains (e.g., physical, cognitive, linguistic, social-emotional).

3. An understanding of each child’s social and cultural background: Early childhood educators learn about and consider each child’s family and community context and family history when crafting the learning environment for that child. This often involves connecting meaningfully with each child’s family to understand the experiences that have shaped the child’s life.

DAP is based on the idea that children learn best when actively engaged in their learning environment. DAP practitioners promote child development and knowledge through active learning more so than through passive receipt of information. ECE environments are often set up to allow for safe exploration and learning through child-directed play, with supportive guidance and scaffolding from practitioners to build on and grow children’s knowledge and skills. At its core, developmentally appropriate practice is grounded in strengths-based, playful learning approaches and aims to ensure that all young children have the support they need to learn and grow in an environment that meets their unique needs.

As noted earlier, guidance on DAP is updated periodically based on the latest research knowledge and understanding. For example, NAEYC’s DAP Guidebook was most recently updated in 2022 for its 4th edition, whereas Pearson—a purveyor of ECE educational materials and training—published a 7th edition of its volume on developmentally appropriate curricula in 2018. DAP guidance and training must be updated periodically to provide the most current and relevant research-based information to ECE educators so that they, in turn, can provide the highest-quality educational experiences and supports to meet the needs of all children.

Four Research-based Facts About DAP

In this section, we make four key points about DAP that are derived from both seminal and more recent research from developmental science. For each point, we make clear that DAP prioritizes being responsive to children and their families, while also ensuring that ECE educators’ practices are grounded in research evidence.

1. DAP aims to help early childhood educators be responsive to each child’s unique needs.

Early childhood education programs serve a wide range of children from birth to age 5. In 2020, over half of U.S. children ages 4 and younger were from Hispanic (26%), Black (14%), Asian (6%), multiracial (5%), and other ethnic groups underrepresented in the overall U.S. population. In 2020-2021, 3.2 percent of infants and toddlers from birth to age 2, and 6.2 percent of preschoolers ages 3 to 5, were served under Part C and Part B, respectively, of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Further, 21.6 percent of U.S. households in 2021 spoke a language other than English.

Developmental science asserts that early learning experiences need to look different for children with different characteristics, such as age (i.e., infants or toddlers vs. preschoolers) or special physical or cognitive needs. Early experiences also need to be tailored for children in a range of contexts, including children living in rural and frontier communities, children living in foster care, children who are recent immigrants, children who are recent refugees, children who are experiencing homelessness, children residing in Native communities, children whose home language is not English—the list goes on. In all cases, ECE educators who understand that multiple contexts shape children’s development know that the supports they provide do not always look the same for each child—and that having a “one size fits all” approach is not conducive to high-quality early childhood teaching practices.

Training in DAP positions ECE educators to take a strengths-based approach by intentionally identifying and appreciating each child’s unique abilities that they bring to the ECE setting.[i]

2. DAP recognizes that a “whole child” approach is central to young children’s learning.

Since its inception, the early childhood field has understood that young children’s learning cannot be compartmentalized. Early childhood educators and researchers have long known that early learning skills across developmental domains—cognitive, linguistic, physical, and social and emotional skills, as well as the ways in which children approach learning—are interconnected and point to the need for a “whole child” approach. For example, getting the most out of a whole-group read-aloud is more difficult when children feel tired or hungry. Moreover, while kindergarten teachers highly value children having strong social-emotional skills—being able to pay attention and learn, take direction from adults, get along well with others, and calm down when upset—these skills tend to be underdeveloped when children begin kindergarten despite research showing that they predict future academic skills.

A whole child approach also recognizes the importance of building children’s positive sense of self—a concept that involves how one feels about oneself and having confidence in what makes one a unique individual—and examines adults’ role in this process. Young children who have a strong sense of self and are confident are more likely to explore their learning environments, show curiosity, try new tasks, and take pride in what they do. However, the science is also clear that the development of a positive sense of self can be threatened for young children if they are subjected to implied negative messaging or a lack of direct supports about the value of their cultures, home language, gender, or other characteristics. Indeed, supporting young children’s racial/ethnic identity development is associated with stronger pre-academic skills, receptive language, behavior, and social development.

Consequently, it is through DAP that early childhood educators ensure they engage in practices that take an integrated—and not an isolated—approach to fostering children’s skills across all developmental domains. This includes making sure that all children feel they are welcomed, encouraged, and supported in all the ways that make them unique and special individuals.

3. Training in DAP is associated with high-quality ECE practices in the classroom.

Several rigorous studies and meta-analyses have shown that providing early childhood educators with professional development focused on developmentally appropriate practices can improve classroom quality in ECE, which may in turn be beneficial for children’s learning and development. DAP is also responsive to evolving pedagogical challenges, emerging research on explicit teaching practices with young children, and the needs of ECE educators and the children they serve in a continual effort to provide high-quality ECE.

While, historically, DAP has emphasized ECE educators engaging children in strengths-based, play-based learning activities, it has evolved based on recent research to support a hybrid approach to early childhood pedagogy where skills-focused teaching methods are embedded in play-centered learning opportunities—also known as “developmentally appropriate academic rigor” or “guided play.” In addition, the evolution of NAEYC’s DAP Guidebook is a direct response to ECE educators’ call for more direct guidance on practices to support the whole child, such as promoting children’s social and emotional skills while preventing challenging behaviors in the classroom.

Similarly, ECE educators have requested more direct guidance on practices that will enhance their capacity to be responsive to the culturally and linguistically diverse children they serve. This would give them the skills they need to honor their commitment to taking a whole child approach and ensuring that all children feel “seen” and that their individual needs are met.

4. DAP promotes strong relationships between educators and families.

Developmentally appropriate practice promotes strong partnerships between educators and families. While the concept of engaging families in ECE programs is not a novel idea, it is receiving more attention than at any time in the past. Family engagement has evolved from “top down” approaches, such as parent involvement activities or parent education, to more authentic, bidirectional partnerships between educators and families. DAP recognizes that fostering secure, stable, and nurturing relationships between adults and young children is the primary vehicle through which all early learning and development occurs. ECE educators who engage in DAP recognize that family partnership is an essential component of effective early learning experiences.

One mechanism for fostering school-family partnerships is to seek out parent/caregiver expertise in children’s learning and incorporate their voice in ECE program delivery. For example, Head Start mandates the creation of a Parent Policy Council in its programs to convey its commitment to a shared governance structure with families in making decisions about local program operations; such mechanisms also provide leadership opportunities for parent/caregiver leaders, who may also serve as a bridge between other families and local Head Start leadership. Another way to foster school-family partnerships is to include family engagement practices as an indicator of quality within state-level Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS). Although QRIS are often voluntary for individual programs to participate, they are designed to support ECE program improvement and provide consumer information about the quality of ECE programs.

ECE educators trained in DAP also demonstrate their commitment to building strong relationships with families by developing a deep awareness and understanding of the structures in which families live, the strengths they bring to ECE, the barriers they face, and the ways in which systemic inequities and disparities inhibit their ability to develop trusting relationships with ECE systems. This awareness and understanding becomes fully realized when all families with young children feel welcome and seen in their child’s ECE program, including families from a range of racial and cultural groups, home language backgrounds, abilities, and family compositions (including, but not limited to, children of LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning) parents, single-parent families, and multi-generational households). Indeed, research shows that children of LGBTQ parents thrive when they experience less stigma and feel supported by their educational environments.

Further, not all families have had equal opportunity to engage in their child’s ECE program for myriad reasons, but DAP shifts the onus to ECE programs to provide opportunities and seek out creative approaches to build relationships with families. ECE educators’ commitment to DAP is a commitment to authentic relationships with children and their families.

Conclusion

Developmentally appropriate practice is a long-standing, gold standard framework for early care and education that is grounded in developmental science research and theory. Taken together, decades of science and research are clear: young children develop and learn best in the context of caring relationships and when learning practices are tailored to their individual needs and characteristics. Educators trained in DAP demonstrate higher-quality classroom practices that support children’s healthy development and other life experiences. Early childhood educators and other professionals are most effective when their practices mirror developmental science, which tells us that all aspects of children’s development must be holistically attended to in early learning environments. DAP also recognizes the critical role of family engagement in child development and learning, and that educators must partner with families to support the whole child. As federal, state, and local leaders seek to support the ECE workforce, it is important that they equip the workforce with tools to incorporate developmentally appropriate, research-based practice into their work.

Footnote

[i] Gestwicki, C. (2010). Developmentally appropriate practice: Curriculum and development in early education (5th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Suggested Citation

LaForett, D.R., Halle, T., & Vivrette, R. (2023). Research shows how developmentally appropriate practice helps early childhood educators support all children. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/1805i6586q

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram