Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences

Over the past several years, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners have increasingly considered ways to prevent or otherwise address the negative effects of ACEs. For example, as of September 2017, 20 states had passed (or had pending) more than 40 bills that specifically mention ACEs, including legislation that establishes task forces to study ACEs and appropriation of funds for ACEs prevention.20,21 One challenge for such efforts is the diversity of experiences that fall under the umbrella of ACEs—from poverty to parental incarceration to community violence—which suggests that no single strategy will be adequate. States and localities address ACEs in a variety of ways that are often tailored to specific issues in local communities, and aimed at addressing multiple problems across sectors. For example, the state of Washington established the ACEs Public-Private Initiative, a collaborative of public agencies, private foundations, and community organizations dedicated to studying and implementing policies and practices that may prevent ACEs. An evaluation found promising positive outcomes in some communities, while noting that all community networks struggled to achieve community-wide change and that no single model worked best for developing the capacity to address ACEs and build resilience.22

While preventing the initial occurrence of ACEs is a logical priority, many children who have already experienced negative effects from ACEs have treatment needs. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians regularly screen young children for circumstances (including maternal depression, parental substance abuse, poverty, and community violence) that can lead to toxic stress.23 If a child has experienced such adversities, health care providers can help the family address the immediate threat and reduce the likelihood of future exposure, and can make referrals to services and to evidence-based treatments that may mitigate the negative effects of the experience. However, the practice of screening for trauma, including ACEs, is not yet widespread among pediatricians.24 The evidence for intergenerational transmission of the effects of ACEs also argues for interventions that work simultaneously with parents and children.25

Conclusions

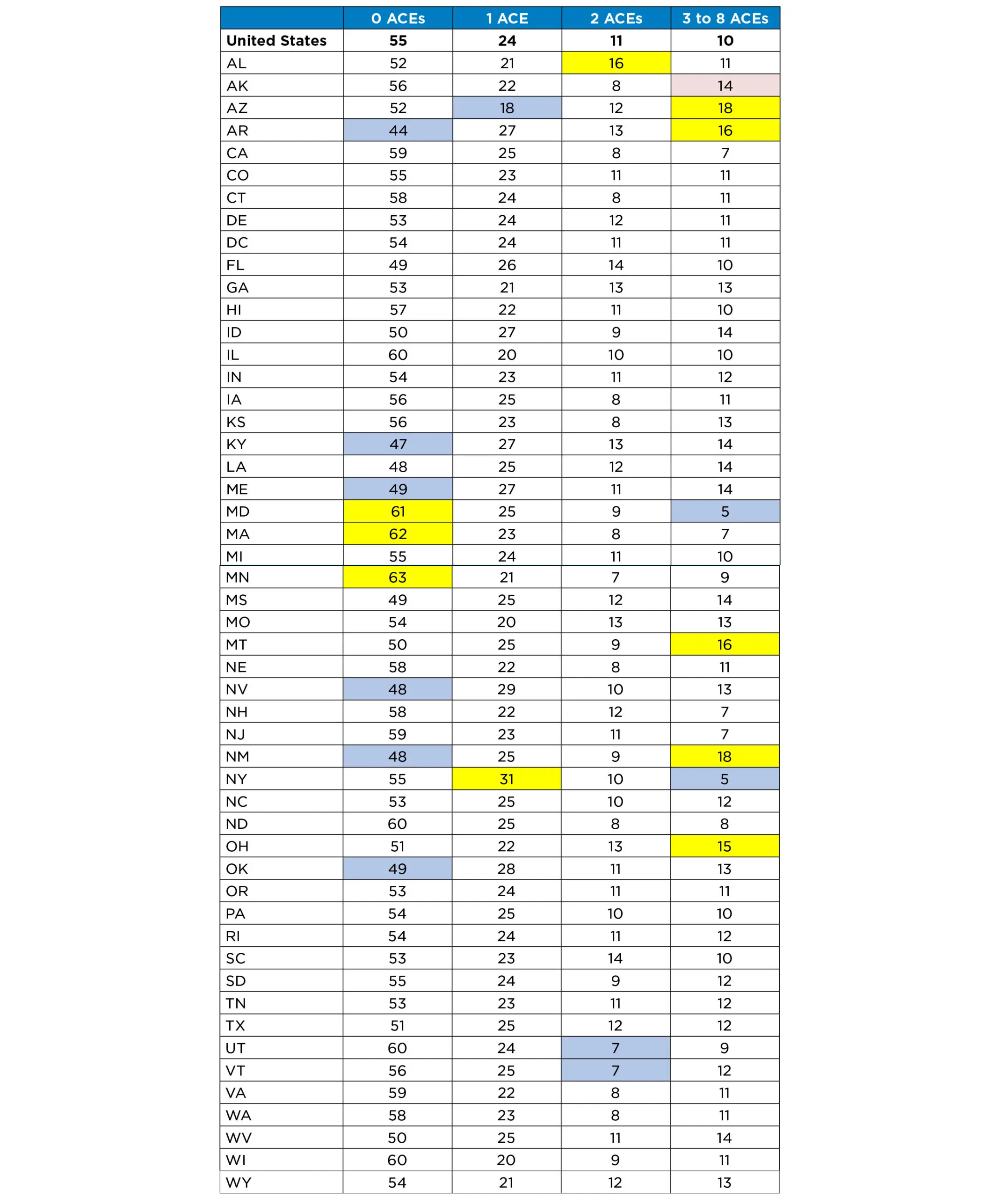

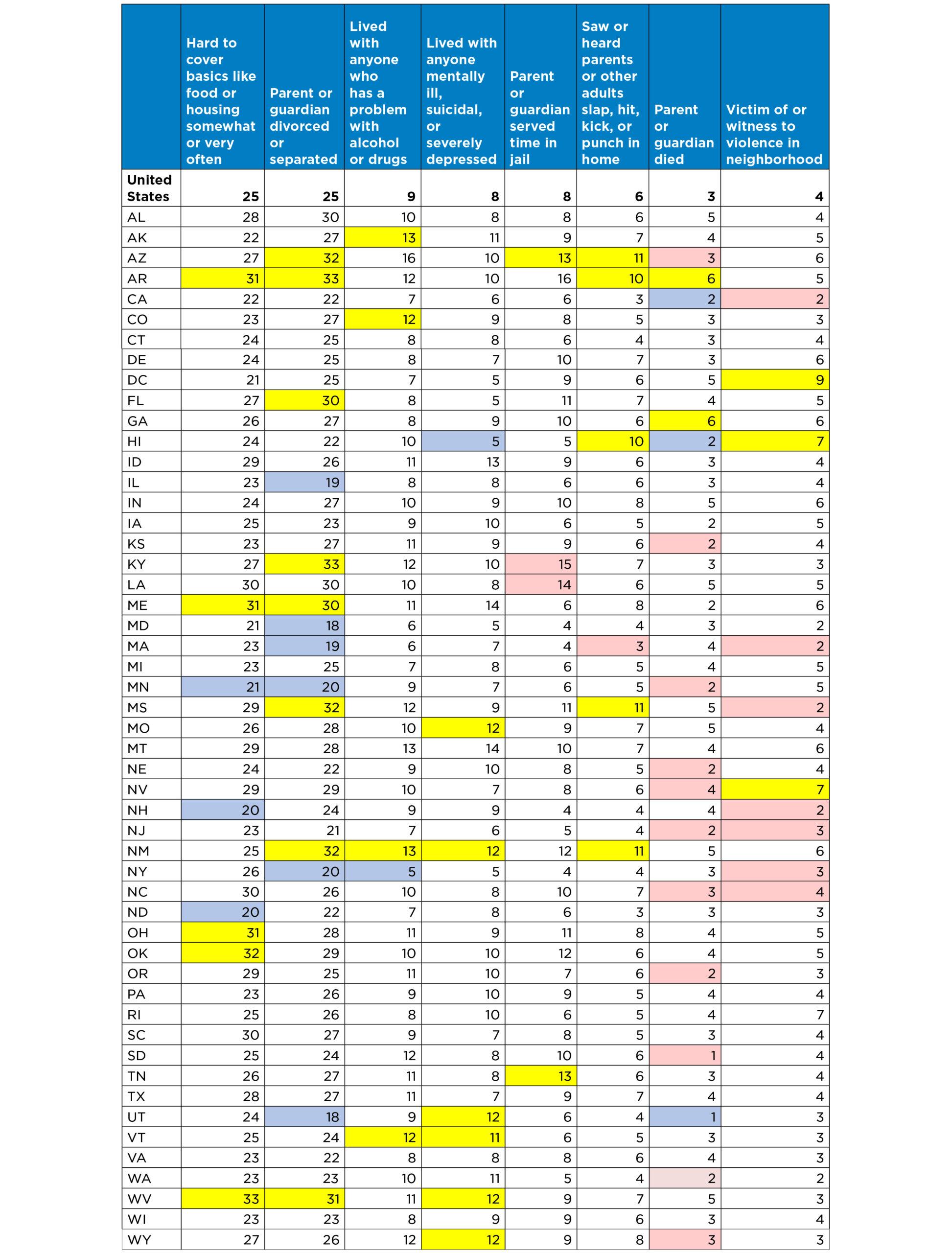

Despite increasing attention—and resources—devoted to preventing adverse childhood experiences and building resilient individuals and communities, ACEs remain common in the United States. Nearly half of all children nationally and in most states have experienced at least one ACE. It is difficult to generalize about the group of states in which children are more likely to have a high number of ACEs. However, among states highest on this measure, three (Arkansas, New Mexico, and Arizona) were among the ten states with the highest child poverty in 2016.35 More robust, multiyear data will be available in the future as ongoing surveying boosts sample sizes.

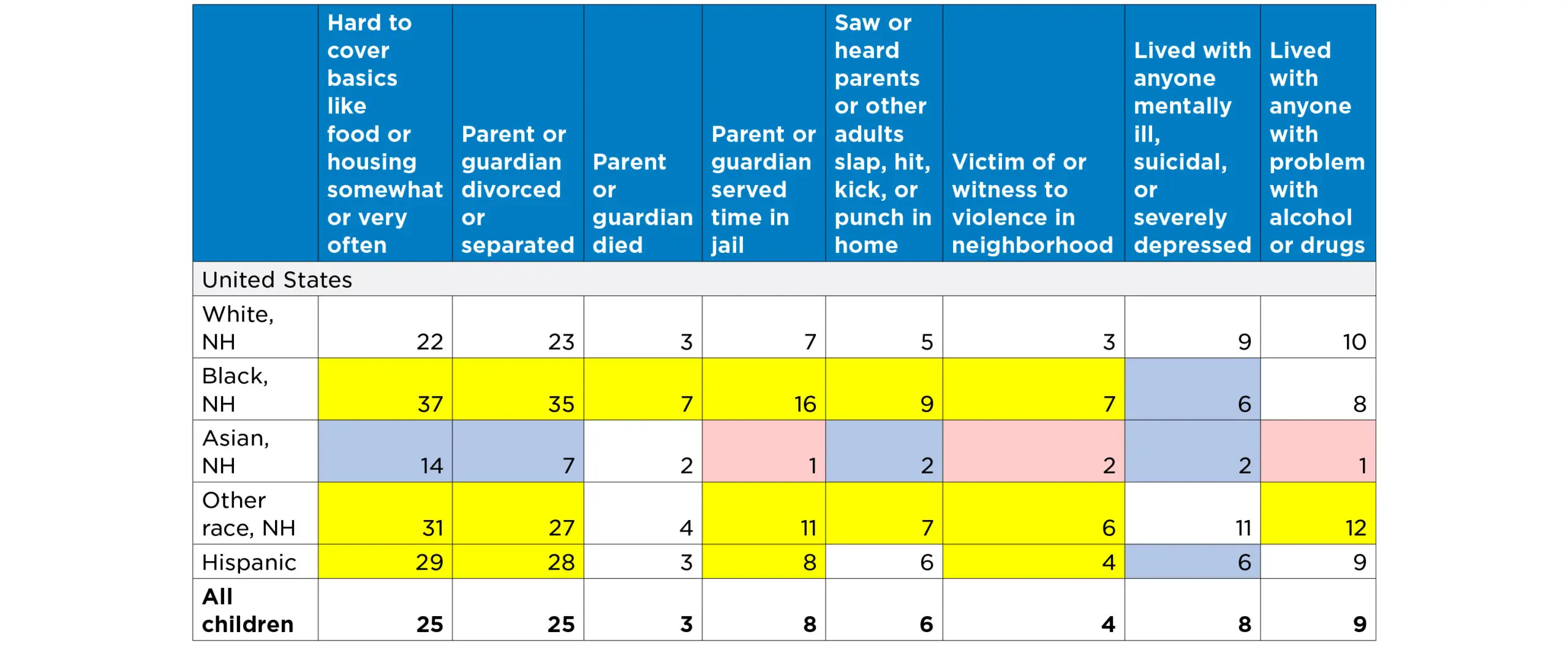

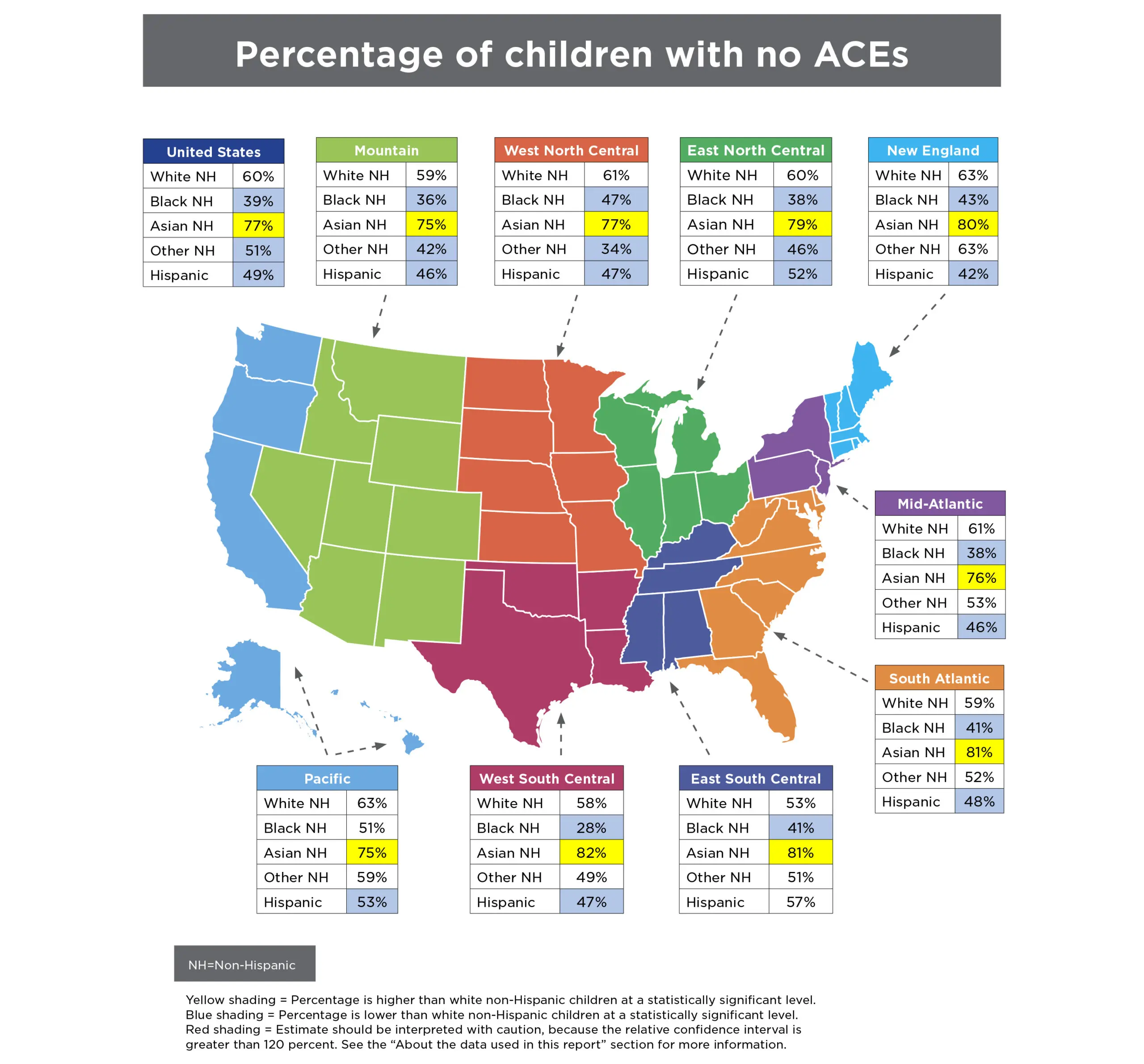

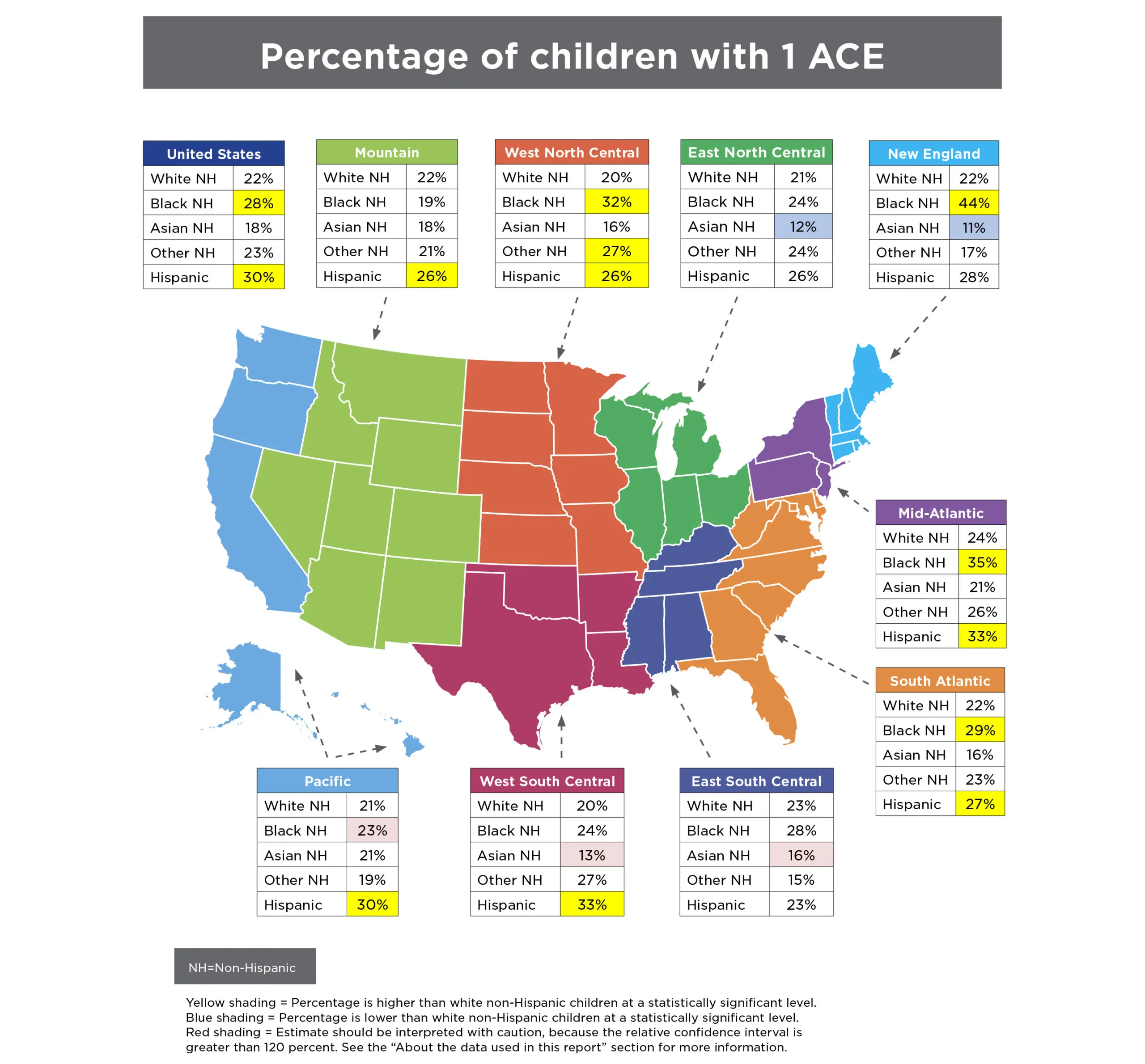

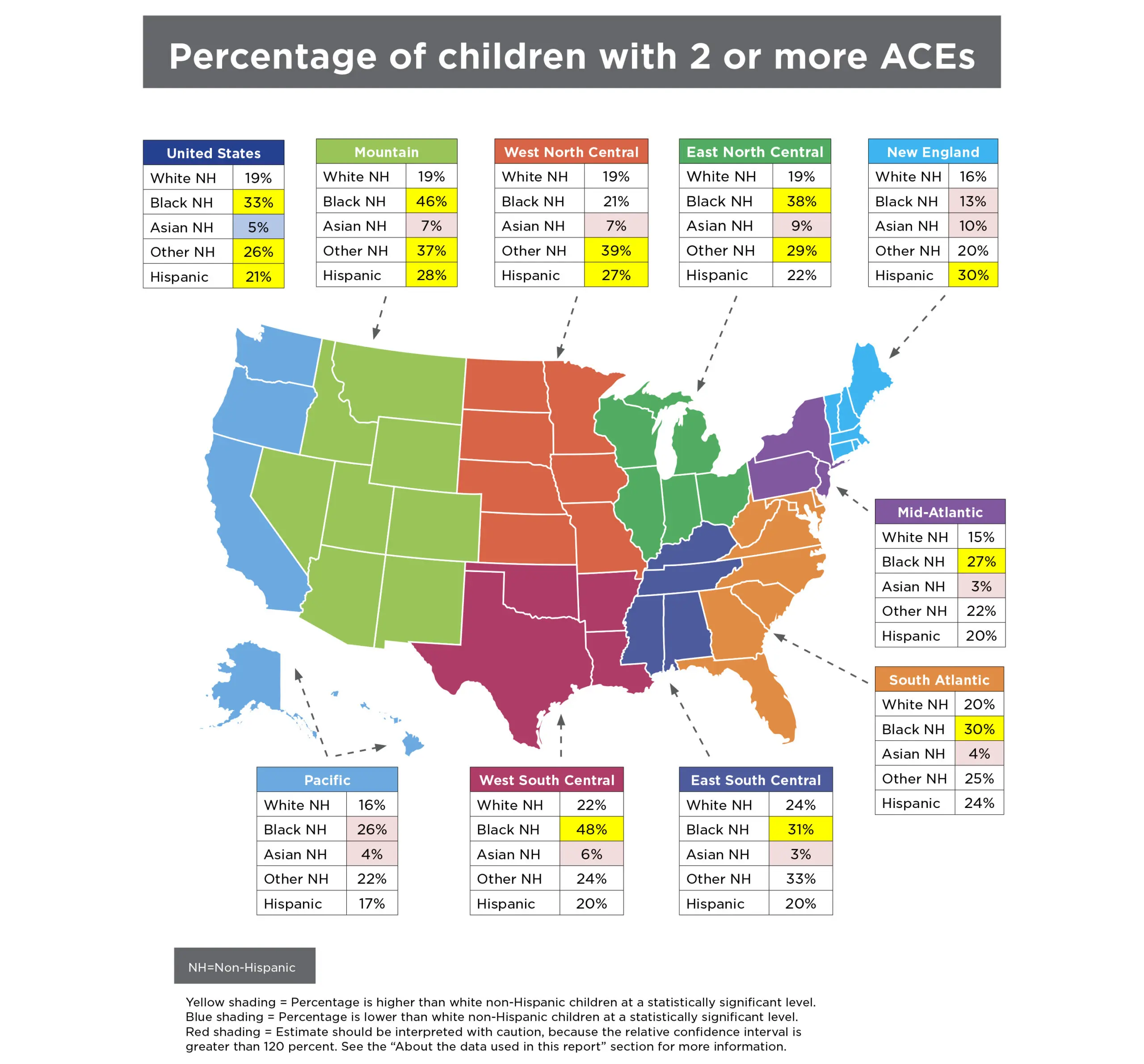

Disturbingly, black and Hispanic children and youth in almost all regions of the United States are more likely to experience ACEs than their white and Asian peers. To some extent, these racial disparities reflect the lasting effects of inequitable policies, practices, and social norms. Discriminatory housing and employment policies, bias in law enforcement and sentencing decisions, and immigration policies have concentrated disadvantage among black and Hispanic children, in particular, and leave them disproportionately vulnerable to traumatic experiences like ACEs.

Along with many other researchers, the study authors believe that the experience of racism can itself have toxic effects.36,37 It may be useful, as some researchers have done, to distinguish between catastrophic (acute) stressors and routine (chronic) ones,38 of which the experience of racism is an example. ACEs (including racism) can make people physically and mentally ill.39 Nevertheless, we believe that the NSCH item asking parents whether their child has been unfairly treated on the basis of race or ethnicity may not adequately assess the full extent—personal, institutional, and systemic—of children’s experience of racism. It may be challenging to accurately assess something with such pervasive (and historically embedded) effects that it may not even be remarked upon.40 There is a need to better understand how both adversity and resilience play out in diverse populations. For example, some evidence suggests that nativity status could be one important factor influencing the effects of ACEs. Hispanic children in immigrant families seem to be buffered from exposure to ACEs, relative to their peers with two U.S.-born parents.41

A number of researchers recommend expanding the concept of ACEs to include community-level stressors.42,43 These stressors may include unsafe neighborhoods, foster care arrangements, and bullying. Limiting surveys to household-level assessments of ACE exposure almost certainly results in underestimates.

The prospect of multigenerational effects stemming from the experience of childhood adversity underscores the urgency of applying a public-health approach to prevention. Such an approach would complement allied perspectives that address social determinants of health, and use intervention models that are explicitly two-generational: focusing simultaneously on the needs of adults (particularly parents) and children who have been exposed (or who are at risk of exposure) to ACEs. Fortunately, a growing number of programs show promise in this field.44 In addition, overdue attention is being given to protective or promotive factors—both of which fall within the concept of resilience.45,46 Adverse experiences do not necessarily lead to toxic levels of stress; here, the buffering role of social support and other protective factors is critical. The cultivation of supportive, protective conditions by parents, by children themselves, and by their broader communities provides an ambitious but essential public health agenda.

About the Data Used in This Brief

The National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) was conducted in 2003, 2007, 2011/12, and 2016 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health was funded and directed by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). The 2016 NSCH was significantly redesigned and differs from the prior survey cycles; therefore, comparisons cannot be drawn across all years of the survey. The survey uses an address-based sample that utilizes internet-based web and mailed paper data collection instruments fielded by the U.S. Census Bureau. One child in each household with children was randomly selected to be the focus of the study. A parent or guardian knowledgeable about the child answered questions about the child and themselves. The survey is representative of children under 18 years of age, both nationwide and within each state. A total of 50,212 surveys were completed.

The prevalence of ACEs described in this brief are derived from the following questions asked of parents:

- To the best of your knowledge, has this child EVER experienced any of the following?

- Parent or guardian divorced or separated (Yes/No)

- Parent or guardian died (Yes/No)

- Parent or guardian served time in jail (Yes/No)

- Saw or heard parents or adults slap, hit, kick, punch one another in the home (Yes/No)

- Was a victim of violence or witnessed violence in his or her neighborhood (Yes/No)

- Lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed (Yes/No)

- Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs (Yes/No)

- SINCE THIS CHILD WAS BORN, how often has it been very hard to get by on your family’s income—hard to cover the basics like food or housing? (Very Often, Somewhat Often, Rarely, Never)

Cases were not included in the analysis if any questions were left unanswered. Six percent of the sample did not answer any of the questions.

The relative confidence interval for each estimate presented in the tables is calculated by dividing the absolute 95 percent confidence interval by the estimate and multiplying by 100. If the relative confidence interval for a given estimate (for example, the percent of black non-Hispanic children with more than one ACE) is more than 120 percent, we suggest that the estimate be interpreted with caution, as it may not be reliable.

Differences between state and national estimates were tested for statistical significance by comparing the 95 percent confidence intervals. If the confidence intervals did not overlap, the differences are marked as significant in the tables.

Differences between the racial/ethnic groups were tested using an ordered logit regression, with white non-Hispanic as the reference group.

Included in the “Other, Non-Hispanic” category are children reported as Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, two or more races, or another race not already listed. For children in these racial categories, there were not sufficient numbers in the 2016 NSCH sample to allow reliable estimates of ACEs for all states or Census divisions.

References

1. Felitti, V. J., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9635069.

2. Sameroff, A., Gutman, L. M., & Peck, S. C. (2003). Adaptation among youth facing multiple risks: Prospective research findings. In S. S. Luthar, Ed., Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Chapt. 15. (pp. 364–391). NY: Cambridge University Press.

4. Moore, K. A., & Ramirez, A. N. (2016). Adverse childhood experience and adolescent well-being: Do protective factors matter? Child Indicators Research, 9(2), 299-316. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12187-015-9324-4.

5. Bethell, C. D., Davis, M. B., Gombojav, N, Stumbo, S., & Powers, K. (2017). A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive. Retrieved from http://www.cahmi.org/projects/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces/.

6. Metzler, M., Merrick, M. T., Klevens, J., Ports, K. A., & Ford, D. C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: shifting the narrative. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 141-149. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916303449.

7. Bethell, C. D., Davis, MB, Gombojav, N, Stumbo, S, Powers, K. (2017). A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive. Retrieved from http://www.cahmi.org/projects/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces/.

8. Chartier, M. J., Walker, J. R., & Naimark, B. (2010). Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(6), 454-464. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0145213410000955.

9. Chapman, D.P., Whitfield, C.L., Felitti, V.J., Dube, S.R., Edwards, V.J, & Anda, R.F. (2004) Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2): 217-225. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15488250.

10. Felitti, V. J. et al. Op cit.

11. Rutter, M. (1979). Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. In M. Kent, & J. Rolf (Eds.), Primary prevention of psychopathology: III. Promoting social competence and coping in children (pp. 49–74). Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/547874.

12. Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J., & Reynolds, A. J. (2013). Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: A cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the US. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 917-925. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4090696/.

13. Buss, C., Entringer, S., Moog, N. K., Toepfer, P., Fair, D. A., Simhan, H. N., & Wadhwa, P. D. (2017). Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal brain development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 56(5). 373–382. Retrieved from http://www.jaacap.com/article/S0890-8567(17)30105-3/fulltext.

14. Monk, C., Feng, T., Lee, S., Krupska, I., Champagne, F. A., & Tycko, B. (2016). Distress during pregnancy: epigenetic regulation of placenta glucocorticoid-related genes and fetal neurobehavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(7), 705-713. Retrieved from https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091171.

15. Almond, D., & Currie, J. (2011). Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 153-172. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4140221/pdf/nihms443660.pdf.

16. Madigan, S., Wade, M., Plamondon, A., Maguire, J. L., & Jenkins, J. M. (2017). Maternal Adverse Childhood Experience and Infant Health: Biomedical and Psychosocial Risks as Intermediary Mechanisms. The Journal of Pediatrics, 187, 282-289.e1. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347617305991

17. Felitti, V. J. et al. Op cit.

18. Bethell, C. D., Carle, A., Hudziak, J., Gombojav, N., Powers, K., Wade, R., & Braveman, P. (2017). Methods to assess adverse childhood experiences of children and families: toward approaches to promote child well-being in policy and practice. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S51-S69. Retrieved from http://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(17)30324-8/abstract.

19. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services: A treatment improvement protocol. Retrieved from https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/SAMSA_TIP_Trauma.pdf.

24. Kerker, B. D., Storfer-Isser, A., Szilagyi, M., Stein, R. E., Garner, A. S., O’Connor, K. G., & Horwitz, S. M. (2016). Do pediatricians ask about adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care? Academic Pediatrics, 16(2), 154-160.

25. Sun, J., Patel, F., Rose-Jacobs, R., Frank, D.A., Black, M.M., Chilton, M. (2017). Mother’s adverse childhood experiences and their young children’s development. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(6), 882-891. Retrieved from: http://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(17)30422-1/pdf.

26. Moore, K. A., & Ramirez, A. N. (2016). Adverse childhood experience and adolescent well-being: Do protective factors matter?. Child Indicators Research, 9(2), 299-316. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/journals_research_update.pdf.

27. Sege, R., Bethell, C., Linkenbach, J., Jones, J.A., Klika, B., Pecora, P.J. (2017). Balancing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) with HOPE*: New insights into the role of positive experience on child and family development. Casey Family Programs. Retrieved from https://www.cssp.org/publications/documents/Balancing-ACEs-with-HOPE-FINAL.pdf.

28. Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., Cameron, J., Duncan, G. J., Fox, N. A., Gunnar, M. R., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, Working Paper, 3, 2014. Retrieved from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_Developing_Brain-1.pdf.

29. Bethell, C. D., Newacheck, P., Hawes, E., & Halfon, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106-2115. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914.

30. American Psychological Assiciation. (2017). Resilience guide for parents & teachers. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/resilience.aspx.

31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

33. Bartlett, D.J., Smith, S., & Bringewatt, E. (2017). Helping young children who have experienced trauma: Policies and strategies for early care and education. Child Trends: Bethesda, MD. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/publications/ecetrauma/.

34. Murphy, K., Moore, Kristin A., Redd, Z., Malm, K. (2017). Trauma-informed child welfare systems and children’s well-being: A longitudinal evaluation of KVC’s bridging the way home initiative. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 23-34. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740917301342

37. Brody, G. H., Yu, T., Miller, G. E., & Chen, E. (2015). Discrimination, Racial Identity, and Cytokine Levels Among African American Adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 56(5), 496–501. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.017.

38. Odgers, C. L., & Jaffee, S. R. (2013). Routine versus catastrophic influences on the developing child. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 29-48. Retrieved from http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114447.

39. Priest, N., Paradies, Y., Trenerry, B., Truong, M., Karlsen, S., & Kelly, Y. (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115-127. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953612007927.

40. Wade, R., Shea, J. A., Rubin, D., & Wood, J. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences of low-income urban youth. Pediatrics, 134(1), e13-e20. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/1/e13.short.

41. Caballero, T. M., Johnson, S. B., Buchanan, C. R. M., & DeCamp, L. R. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Hispanic Children in Immigrant Families Versus US-Native Families. Pediatrics, 140(5), e20170297. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/140/5/e20170297.

42. Cronholm, P.F., Forke, C.M, Wade, R., Bair-Merritt, M.H., Davis, M., Harkins-Schwarz, M., Pachter, L.M., Fein, J.A., (2015). Adverse Childhood Experiences Expanding the Concept of Adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354-361. Retrieved from: http://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(15)00050-1/pdf.

43. Bruner, C. (2017). ACE, Place, Race, and Poverty: Building Hope for Children. Community and Family Approaches, 17(7S), S123-S129. Retrieved from: http://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(17)30352-2/pdf.

44. Bartlett, Dym J., Smith, S., & Bringewatt, E. (2017). Helping young children who have experienced trauma: Policies and strategies for early care and education. Child Trends: Bethesda, MD. Retrieved from https://childtrends-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-19ECETrauma.pdf.

45. Traub, F., & Boynton-Jarrett, R. (2017). Modifiable Resilience Factors to Childhood Adversity for Clinical Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics, e20162569. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2017/04/17/peds.2016-2569.

46. Traub, F. E. (2016). Factors for improving short-and long-term health outcomes for children who have experienced adversity and trauma (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/19471/Traub_bu_0017N_12325.pdf?sequence=1.

This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation. We would also like to thank Jessica Dym Bartlett, Maria A. Ramos-Olazagasti, Kristine Andrews, and Kristin Moore for their review.