While sexual and reproductive health (SRH) education and services help adolescents more safely navigate their early relationships and sexual experiences, these services are too often inequitably distributed and unavailable to students from minoritized communities. As a result, while up to one third of female adolescents may be sexually active, the types of SRH services they receive can vary significantly by their race and ethnicity. School-based health centers and other in-school settings can help close the racial and ethnic gap by providing critical SRH services to students in settings that are more conducive to their circumstances, comfort levels, and sense of empowerment.

Download

Adolescence (ages 10-19) is a critical period in which youth experience significant brain development and begin taking risks, developing autonomy, and exploring new social relationships. It is normal for many adolescents to begin exploring their sexuality and engaging in sexual activity, which underscores the importance of ensuring their access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services such as contraceptive counseling, contraceptive prescriptions or insertions, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and pregnancy testing. For many adolescents, access to SRH services means that early romantic relationships—important opportunities for meaningful connections and sexual exploration that can shape their future relationships and sexual activity—can be safe and positive experiences.

However, without access to these SRH services, sexual activity for many adolescents may coincide with stressful experiences such as STI contraction, pregnancy scares, unplanned pregnancies, or other adverse sexual health outcomes. Despite significant declines in recent decades, the United States still has the highest rate of teen pregnancy among industrialized nations. Young people (ages 15-24) in the United States are also disproportionally burdened by STIs and account for over half of all new STIs despite comprising only one quarter of the sexually active population. Moreover, Black, Hispanic, and Native American young people have significantly higher rates of unplanned pregnancy and STIs than their White counterparts—a result of unequal access to SRH services, low levels of sex education, higher rates of provider distrust (often due to provider bias and experiences of discrimination when receiving care), and lower rates of effective contraceptive use. Although research documents disparities in access to SRH services by race and ethnicity, researchers have yet to explore whether there are differences, if any, in the types of SRH services received by different populations.

In this brief, we first address the importance of school-based health centers (SBHCs) for providing needed SRH services in a setting conducive to adolescents’ needs. Next, we briefly outline our data source and methodology for this study. Then, we outline our findings on the overall prevalence of sexual activity among female high school students, their receipt of SRH services, and the ways in which receipt of SRH services vary based on race and ethnicity. Finally, we discuss various implications of our findings and offer recommendations for improving receipt of SRH services among adolescents.

SBHCs Are Essential Sexual and Reproductive Health Providers

Access to SRH services can reduce unplanned pregnancies and STIs among adolescents by increasing their SRH knowledge and reducing barriers to care. Despite research suggesting that access to SRH services is critical for positive reproductive health outcomes, adolescents face multiple barriers to SRH care, including confidentiality concerns or fear of their parents finding out, mistrust of contraceptives, and limited access to care (e.g., transportation, cost, lack of teen-friendly clinic hours). One way to provide access to SRH services for adolescents is through school-based health centers (SBHCs). SBHCs are well-positioned to reduce barriers to SRH services for adolescents since they can offer convenient, in-school reproductive health care services at low cost without requiring students to travel elsewhere for an appointment. Several studies indicate that SBHCs are a promising way to help reduce teen pregnancy and STI rates among adolescents. They are particularly promising for low-income adolescents and Black and Hispanic adolescents. However, the United States has only approximately 2,500 SBHCs, less than half of which provide adolescents with contraception—indicating that many adolescents lack access to confidential SRH services at a convenient location. Expanding access to SRH services through SBHCs could fill an important gap in access for adolescents and reduce disparities in services received by race and ethnicity.

Methodology and Data

We used the 2011-2019 waves of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to examine sexual activity and receipt of SRH services among young women (who self-reported their sex as female). The sample was restricted to females ages 15 to 19 who reported currently being enrolled in high school in the United States and who identified as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White (N=2,475). Findings from these data are limited by small sample sizes (N=450 for females sexually active in the past 12 months) and prevent us from looking at race/ethnic categories outside of non-Hispanic White (referred to as White), non-Hispanic Black (referred to as Black), and Hispanic. Future research with larger samples of young people will be critical for advancing the field of adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

To assess sexual activity, we used participants’ responses to the following question: “At any time in your life, have you ever had sexual intercourse with a man, that is, made love, had sex, or gone all the way? NOTE: Do not count oral sex, anal sex, heavy petting, or other forms of sexual activity that do not involve vaginal penetration. Do not count sex with a female partner.” This question does not delineate between forced and consensual sex, so there may be instances in our sample where sexually activity in the past 12 months was not wanted. The NSFG does include a question about forced sex and, as of 2015, estimated that 19 percent of women ages 18 to 44 have been forced by a male to have unwanted sexual intercourse at some point in their lives. For questions related to receipt of SRH services, survey respondents were asked to select all services they had ever received in the past 12 months. The services included pregnancy test, birth control, birth control counseling, emergency contraception, emergency contraception counseling, and STI testing.

To assess sexual activity, receipt of SRH services, and differences by race/ethnicity, we conducted cross tabulations to assess descriptive statistics and adjusted Wald tests to test for significant differences across groups. All analyses were conducted with Stata 16.1 and estimates were weighted using the combined 2011-2019 NSFG female respondent weights; however, raw sample sizes are presented for reference.

Findings

Prevalence of sexual activity

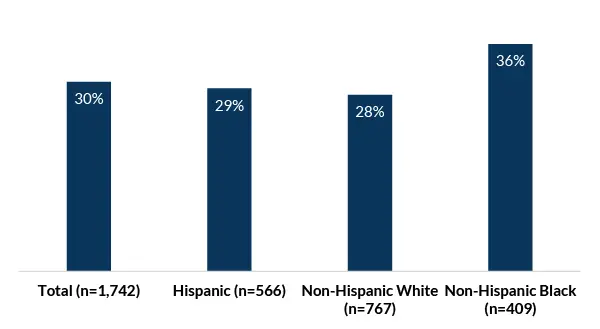

Nearly one third (30%) of female high school students have ever had sexual intercourse and 27 percent have had sex in the past 12 months (see Figure 1). Although none of the differences between racial/ethnic groups were statistically significant, the differences appear large and may be substantive if using a larger sample size.

Figure 1. Sexual activity[1] among female high school students ages 15 to 19, by race/Hispanic ethnicity (N=1,742), in weighted percentages

Receipt of SRH services among sexually active adolescents

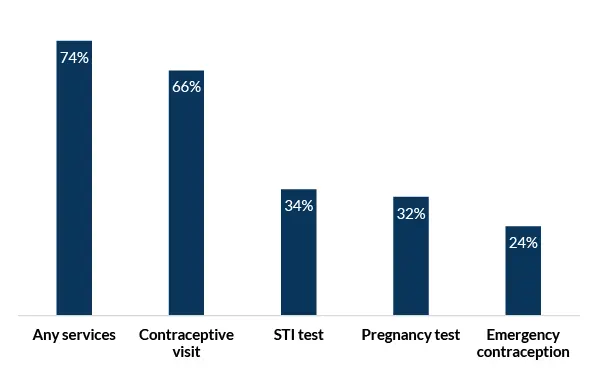

More than one quarter (26%) of high school females who have had sex in the past 12 months have not received any SRH services (see Figure 2). Two thirds of sexually active females (66%) had a contraceptive-related visit in which they received contraceptive counseling, a birth control method/prescription, or a birth control checkup. One third of sexually active females have received an STI test (34%) and/or a pregnancy test (32%), and one quarter (24%) have received emergency contraception (EC) or EC counseling.

Figure 2. Receipt of sexual and reproductive health services among female high school students (ages 15-19) who have had sex in the past 12 months (N=450), in weighted percentages

Variation in SRH service receipt by race and ethnicity

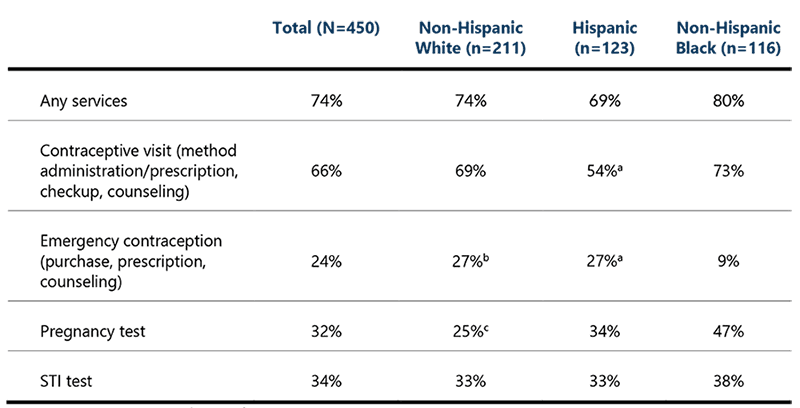

Table 1 shows that rates for receipt of any SRH services in the past 12 months did not differ significantly across racial/Hispanic ethnicity groups despite seemingly large numerical differences. However, disaggregating types of service by race/Hispanic ethnicity reveals differences in types of SRH services received across groups, some of which are striking. We found that:

- Hispanic female high school students were significantly less likely (54%) than Black females (73%) to have had a contraceptive-related visit in the past 12 months.

- Black female high school students were significantly less likely (9%) than Hispanic females (27%) and marginally less likely than White females to have received EC or EC counseling in the past 12 months.

- White female high school students were significantly less likely (33%) than Black females (47%) to have taken a pregnancy test in the past 12 months.

- There were no significant differences in receipt of an STI test in the past 12 months by race/Hispanic ethnicity.

Table 1. Receipt of SRH services among female high school students (ages 15-19) who have had sex in the past 12 months, by race/ethnicity (N=450)

Notes

Discussion of Findings

Prevalence of sexual activity

As with previous studies, we did not find differences in sexual experience or sexual activity among female high school students by race/Hispanic ethnicity, although future studies with larger sample sizes may find meaningful differences. While this lack of differences may be a result of relatively small sample sizes (N=566 Hispanic respondents, 767 White respondents, and 409 Black respondents), it is also an important indicator that sexual activity for adolescents ages 15 to 19 is a normative and appropriate behavior, when consensual.

Receipt of SRH services among sexually active adolescents

Over one quarter of sexually active high school females have not received any SRH services in the past 12 months, and one third did not access contraceptive counseling or services—highlighting an important gap that needs to be filled. A potential way to address this gap is to bring SRH services to the location at which young people spend a large amount of their time: school. Increasing the number of SBHCs that provide these services confidentially and without cost could increase students’ knowledge of and access to contraceptive and STI services.

By offering SRH services in a school-based setting, SBHCs allow young people to engage with a health care provider, learn how to ask questions, and develop feelings of safety in medical settings. Interaction with health care providers in a confidential setting is particularly important since many young people may not have parents who are able to take them to routine health appointments. Even young people who do have a primary care provider may not feel comfortable talking to their provider or may be unable to do so privately if their parent is in the room. SBHCs always encourage young people to involve their parents in health-related decision making, but some students do not feel safe or supported by their parents and need confidential care. Creating time and space for confidential conversations with adolescents is aligned with guidance in adolescent medicine. Additionally, SBHCs can provide an essential element in adolescents’ transition to adult care by teaching them to speak to providers on their own and advocate for themselves. Parents can support their teens by encouraging conversations with providers without being present in the room themselves; SBHCs are uniquely situated to support this kind of growth.

By offering SRH services in an accessible and confidential location, more young people can access the services they need. Ultimately, increasing the receipt of SRH services among young people may lower rates of unintended pregnancy and STIs and increase young people’s reproductive autonomy.

Disparities in receipt of SRH services among sexually active adolescents

Among female high school students who had received SRH services in the past 12 months, we found striking differences in the types of services received by race/Hispanic ethnicity. Notably, Hispanic females were less likely than Black females to have had a contraceptive-related visit in the past 12 months; Black females were less likely than Hispanic females to have had an emergency contraception-related visit; and non-Hispanic White females were less likely than Black females to have taken a pregnancy test. Although the data do not explain these interesting nuances in receipt of certain types of SRH services by race/ethnicity, existing literature can offer potential explanations.

While two thirds of all sexually active high school females reported a contraceptive-related visit, almost half of Hispanic females did not. Hispanic women may be less likely to have contraceptive-related visits due to lower levels of trust in health care as a result of historic and current discriminatory practices, lower contraceptive knowledge, fear of side effects, and higher perceived infertility. Some studies have also found that early pregnancy is accepted and even desirable among many Hispanic cultures, which may also result in lower levels of contraceptive use among young women, although other research has found that most Hispanic teens do not want to experience a pregnancy. However, this cultural norm may inhibit young Hispanic women who want to use contraception from knowing where to go or how to arrange transportation or finances to obtain contraception. This lack of knowledge is further exacerbated by the lack of comprehensive sex education across the United States.

Almost one quarter of sexually active high school females either purchased emergency contraception (EC) or received EC services from a health care provider, indicating potentially inconsistent contraceptive use or potential pregnancy scares. Lower levels of taking or receiving a prescription for EC among Black women may be attributed to barriers to accessing EC, such as a lack of knowledge of and misinformation about EC, a dearth of accessible pharmacies, lack of financial resources or transportation to purchase EC, or fears about confidentiality or embarrassment when purchasing EC in a public pharmacy. Additionally, research has found that Black women report more concern about hormonal methods than other women, indicating that some Black women may be concerned about EC (a hormonal method) and afraid of its side effects.

Almost one third of high school females have received a pregnancy test in the past year, which may be due to either pregnancy scares or provider requirements for pregnancy tests as part of contraceptive counseling. We found that rates of pregnancy testing were highest for Black female high school students, which may be attributed to higher rates of contraceptive-related visits among Black women in our sample. It has also been documented that Black women are more likely to rely on less effective contraceptive methods, which may result in more anxiety around potential pregnancy and more frequent pregnancy testing. Future research should assess whether there are differences in clinician administration of pregnancy tests by race or ethnicity.

Although we found no differences in STI testing by race/Hispanic ethnicity, only one third of sexually active high school females in the sample had received an STI test in the past 12 months. This is concerning considering the high rates of STIs in the young adult population. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends annual testing for STIs among sexually active individuals younger than age 25.

Recommendations

Overall, a lack of comprehensive sex education—and resulting lack of knowledge about contraceptive methods and STIs, and where or how to obtain contraception—likely contributes to the low SRH use we found in this study. Providers and staff in programs serving adolescents can improve receipt of SRH services by:

- Increasing the number of SBHCs, and specifically of SBHCs that provide confidential contraceptive services

- Administering comprehensive sexual education, within or outside the SBHC setting, that provides adolescents with information about where they can go for SRH services

- Ensuring that SBHCs are teen-friendly and that adolescents feel safe and comfortable in those spaces

- Educating SBHCs on how to provide patient-centered care—including the use of a racial justice framework—to help address disparities in receipt of SRH services among young people

- Increasing the visibility of SBHCs so that adolescents recognize them as sources of trusted information and care

- Providing adolescents with full information about the confidentiality policies of their SBHC and on the costs for services, if any

Limitations

Limitations to this study include reliance on secondary analysis of the NSFG, which does not include comprehensive information on sexual orientation and gender identity. This, in turn, prevents us from being able to speak to the experiences of LGBTQ+ teens or teens who do not identify as male or female—populations that are inadequately served by sex education and often experience discrimination when seeking SRH care. Additionally, the dataset has relatively small sample sizes for adolescent populations, which reduces our ability to examine racial/ethnic differences beyond Black, White, and Hispanic teens. However, this study did find interesting nuances in receipt of SRH services by race/Hispanic ethnicity that are overlooked when we focus only on the total population. These racial and ethnic differences are important for providers and researchers to be aware of when trying to close gaps in access to SRH services for young people. Although not addressed in this brief, providers, clinicians, and researchers should invest more resources in understanding what drives these differences and whether they are behavioral, normative, or based in biases.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

Suggested Citation

Whitfield, B., Lantos, H., & Manlove, J. (2022). Offering Sexual and Reproductive Health Services to Adolescents in School Settings Can Create More Equitable Access. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/5915b4336o

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram