As the COVID-19 pandemic persists, students continue to face significant challenges to their mental and physical health. In an April 2020 survey from Active Minds, 60 percent of high school students reported that their mental health has worsened during the pandemic. Pandemic-related school closures have also caused many students to lose access to necessary school-based health services. Students with disabilities and special health care needs, who may heavily rely on services typically provided at school, are even more likely to experience disruptions to needed health care as a result of COVID-19. Further, many students are no longer receiving crucial school nutrition services. Among households with children who qualify for free or reduced-price school meals, only 15 percent regularly receive school meals during COVID-19 school closures. As districts work to address these challenges while simultaneously grappling with difficult reopening decisions, many are looking to state education agencies for guidance.

The challenges students face during COVID-19 demand thoughtful coordination between education and health agencies. A coordinated approach to school health that incorporates all facets of student well-being is critical for states looking to provide districts with holistic guidance for supporting students across a range of physical and mental health needs. All states have released recommendations for reopening schools, many of which address various aspects of student health and well-being. However, these recommendations include gaps in both the comprehensiveness and specificity of guidance with respect to how schools should support the whole child during the pandemic.

How state plans can guide district actions

State reopening plans were coded based on two features that may be helpful to districts as they decide how to reopen schools and provide supports to students during the pandemic: phase of reopening and strength of guidance.

- Phase of reopening refers to whether guidance is specific to in-person, hybrid, or entirely remote learning settings—or whether guidance is general, meaning that the phase of reopening was not specified in the state plan.

- Strength of guidance reflects whether the state reopening plan requires (or mandates), recommends, or encourages districts to implement a given policy or practice.

These two features reflect key concerns of districts related to reopening plans: how to implement practices in novel learning settings and how urgently districts must implement them.

Child Trends conducted an analysis of state school reopening plans for all 50 states and the District of Columbia in terms of their recommendations for topics relevant to the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model of school health. The WSCC model is a framework from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for addressing health in schools, which includes 10 fundamental components that align common goals of the education and health sectors in supporting students. State reopening plans were coded for their inclusion of topics related to each WSCC component generally (see Appendix), as well as those particular to each phase of school reopening. Plans were also coded for the strength of guidance used to address each WSCC component. Key findings and takeaways of the analyses are presented below in four maps, three of which are interactive.

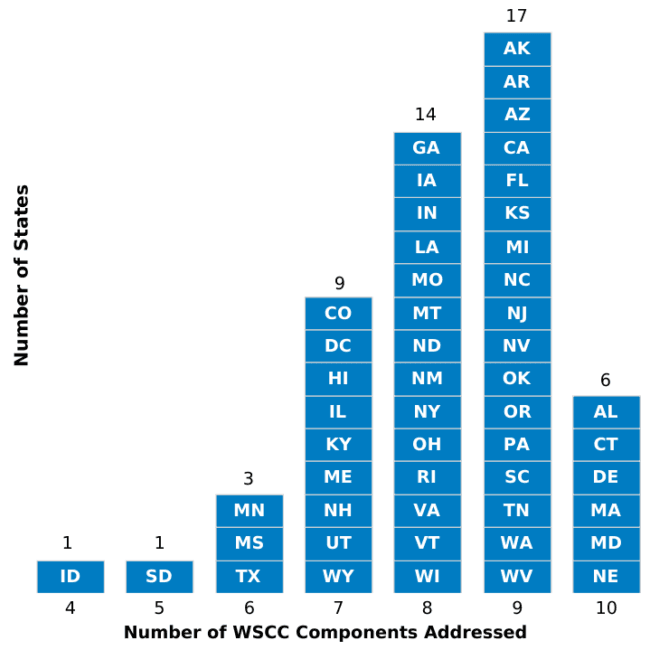

Figure 1. Total number of WSCC components addressed in each state reopening plan

Most states provide guidance related to a majority of the WSCC model’s 10 components, but critical components are commonly overlooked.

Our analysis finds that 46 states include at least seven (of the 10) components of the WSCC model in their reopening plans (see Figure 1).* Social and Emotional Climate is addressed the least in state reopening plans, with 12 states omitting any sort of guidance for related topics (see Figure 2). Given the known impacts of the pandemic on student emotional well-being, districts may need guidance from states about effectively supporting students’ socioemotional needs. By contrast, the Physical Environment component is addressed most often in state reopening plans, with 49 states providing related guidance—likely reflecting the need for strict cleaning, masking, and social distancing practices.

Figure 2. WSCC components addressed by each state

To view which state plans addressed each WSCC component, select a WSCC component below.

Less than 15 percent of state reopening plans include policy and practice requirements related to social and emotional well-being.

State guidance most frequently includes requirements related to components of the WSCC model that address school cleaning protocols, health referrals, and school nurses; this is anticipated given the demands of COVID-19. Twenty-three and 17 states, respectively, have established requirements related to Physical Environment and Health Services in their reopening plans (see Figure 3). However, fewer than 10 states include requirements related to non-physical health and wellness supports for students, including Social and Emotional Climate and Counseling, Psychological, and Social Services. In districts where resources are limited, requirements that target only physical health could unintentionally draw attention and resources away from the social-emotional and mental health needs of students.

Figure 3. WSCC components addressed by each state, by level of guidance

To view which state plans addressed each WSCC component with policy or practice requirements, select a WSCC component below.

Most state reopening plans do not provide comprehensive guidance specific to each phase of reopening.

Our analysis also finds variation in state guidance with respect to states’ consideration of in-person, hybrid, or entirely remote reopening scenarios. Most states address WSCC components without explicitly referencing the different ways in which each component should be applied within a specific phase of reopening. For example, 41 states provide general guidance related to Health Services (see Figure 4). However, only 14 states provide guidance for Health Services specifically during in-person learning, and only six provide guidance for Health Services when learning is entirely remote. While general state directives can give districts the flexibility to interpret and apply guidance based on local need, the provision of school health services will look vastly different during in-person versus remote learning periods. Districts may need guidance for all phases of reopening so they are prepared to provide services to students in all learning settings, particularly if shifts in the COVID-19 pandemic require sudden school closures or openings. Efforts to track state and local school closures suggest considerable flux in terms of whether schools are open or closed for any in-person learning. Accordingly, guidance based on phase of reopening could help districts provide services and supports in support of elements of the WSCC model.

Other WSCC components related to the provision of direct services to students—including Nutrition Environment and Services; Social and Emotional Climate; and Counseling, Psychological, and Social Services—are vulnerable to significant shifts in implementation during remote versus in-person learning settings. However, state plans do not often address different options for service delivery, depending on which reopening phase districts are operating under. For instance, 36 states address Nutrition Environment and Services generally in their reopening plans, but only 14 include specific guidance for providing school meals and nutrition services in entirely remote learning scenarios (see Figure 4). Early in the pandemic, districts urgently needed state support for meal distribution during school closures. Yet remote learning guidance for Nutrition Environment and Services is rarely present in state reopening plans, presenting potential challenges for districts using an entirely remote learning model or those that may return to one as the pandemic evolves.

Figure 4. WSCC components addressed by each state, by phase of reopening

To view which state plans addressed each WSCC component in guidance specific to a certain reopening phase, select a WSCC component and a reopening phase below.

Conclusions

This analysis has identified gaps that state education agencies could fill as districts continue to navigate complicated school reopening decisions while educating students and supporting their diverse needs. States can provide districts with comprehensive guidance for supporting student health and well-being while also allowing them the flexibility to meet the unique needs of their communities. In addition, it is imperative that state education agencies and state and local health officials coordinate to provide districts with well-rounded and concrete guidance for supporting overall student health and well-being.

* Only 15 states include the Health Education component of the WSCC model in their school reopening plans. We have excluded this component from our analyses because it may be covered by curriculum-specific reopening guidance, rather than overall reopening guidance related to school health.

Note on Methodology

Appendix: WSCC Components and Topics Coded in State Reopening Plans

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram