Note: We have added the word “some” to the first sentence, which we inadvertently dropped during editing. Our apologies.

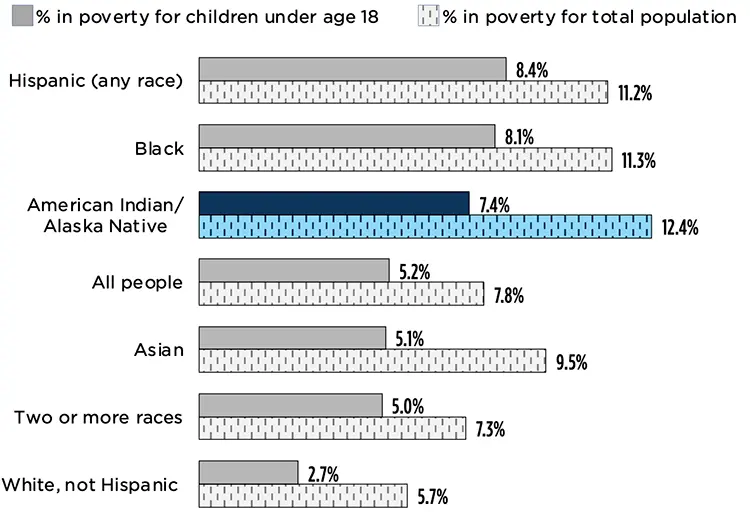

In 2021, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children under age 18 and the overall AIAN population disproportionately experienced poverty when compared to some other racial and ethnic population groups, according to the latest report from the U.S. Census Bureau featuring Supplemental Poverty Measure estimates (see Figure below). The estimated percentage of children living in poverty was 8.4 percent for Hispanic children, 8.1 percent for Black children, and 7.4 percent for AIAN children—each more than twice the estimate for White non-Hispanic children (2.7%). For the overall population, the estimated percentage living in poverty was highest among the AIAN population (12.4%)—compared to Black (11.3%), Hispanic (11.2%), and White non-Hispanic (5.7%)—regardless of the poverty measure used.[1] This is the first time the Census has included poverty estimates for the AIAN population in its report on poverty in the United States.

2021 Census estimates show disproportionate poverty among AIAN children, and the overall AIAN population

Estimated poverty rates using the U.S. Census Bureau Supplemental Poverty Measure, by age, race, and Hispanic ethnicity (2021)

Source and Notes

Historic and ongoing colonization results in intergenerational and historical trauma that drives high rates of poverty for Indigenous children and families. For example, lasting impacts of colonial removal policies, assimilation practices, and restrictions on Tribal self-determination have become embedded in the U.S. economy through structural racism; this, in turn, contributes to high unemployment, limited educational opportunities, loss of construction and manufacturing jobs, struggling reservation economies, and wage discrimination. Today, many Indigenous communities still lack adequate internet infrastructure, which further inhibits participation in education and employment opportunities (e.g., remote education and work, access to information about employment opportunities). Land theft through colonization—estimated to have resulted in the loss of 99 percent of Indigenous land in the contiguous United States and 90 percent of Indigenous land in Alaska—has also severely impacted the AIAN population’s access to economic benefits related to agricultural, timber, oil and gas, and mineral resources.

Culture, language, and community may serve as protective factors for Indigenous people experiencing poverty in unique and powerful ways. First, these protective factors increase Indigenous people’s access to resources and supports through extended family and community networks that mitigate mental, physical, financial, and social health disparities linked to poverty. Second, they help create welcoming spaces in schools and higher education settings that promote educational achievement and decrease risk of unemployment. Tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) play a specific role in addressing poverty by providing access to culturally specific learning, local jobs, technology, training, and mentorship; they also serve many first-generation college students and provide supports such as child care to facilitate access to higher education for parenting students.

Policy and practice strategies to address poverty—for AIAN children and the overall AIAN population—must be grounded in an understanding of the past, designed to be meaningful to the cultures and value systems of Indigenous communities today, and promote livable wages and supplemental supports for families. Recent analysis from Child Trends found a historic decline in child poverty nationally over the last quarter century, due in part to growth in the federal social safety net (e.g., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). While these analyses were not able to disaggregate findings for AIAN children due to small sample sizes, the Census Bureau’s poverty estimates suggest that further research is needed to understand the impact of the social safety net for AIAN populations, including the role that Tribal-specific supports may play in reducing the number of AIAN children growing up in poverty.

Related Research

- American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) Children Are Overrepresented in Foster Care in States With the Largest Proportions of AIAN Children

- Federal Policies That Contribute to Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities and Potential Solutions for Indigenous Children, Families, and Communities

- Lessons From a Historic Decline in Child Poverty

- Meet Our Researchers: Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon

- Meet Our Researchers: Deana Around Him

The authors would like to thank Elizabeth Jordan, Renee Ryberg, Dana Thomson, Astha Patel, and the Child Trends communications team for their reviews of and contributions to this piece.

Endnote

[1] The Census report cited for this analysis includes AIAN poverty estimates using the Census Bureau’s official poverty measure (OPM) and Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). We prefer the SPM estimates because they account for a broader range of resources and supports available to households (e.g., income plus some nonmonetary resources from government programs and tax credits to families with low incomes) than the OPM, which is based on pretax income relative to a poverty threshold adjusted for family composition. Regardless of the poverty measure used, estimates indicate that the overall AIAN population is disproportionately likely to experience poverty relative to all other racial and ethnic groups shown in the figure.

Suggested Citation: Around Him, D., & Gordon, H. S. J. (2022). Latest Census estimates show disproportionate poverty among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children and the overall AIAN population. Child Trends. https://childtrends.org/blog/latest-census-estimates-show-disproportionate-poverty-among-american-indian-and-alaska-native-aian-children-and-the-overall-aian-population

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram