Authors

Yiyu Chen is the lead author, and James Fuller and Renee Ryberg contributed equally to this brief.

The ways poverty is measured can influence how we, as a country, understand what it means to live in poverty. Poverty measures inform the work of policymakers, practitioners, and advocates to address poverty and prevent the adverse consequences associated with it. This brief summarizes basic attributes of the range of poverty measures used in the United States, as well as their strengths and limitations. Our goal is to give policy analysts and researchers the tools to appropriately interpret poverty statistics and decide when to use which measure.

In this brief, we first review two major categories of poverty measures—absolute and relative measures—as well as basic elements of a poverty measure: economic resources and thresholds. Second, we introduce poverty measures commonly used in the United States, including the U.S. Official Poverty Measure (OPM) (an absolute measure), examples of relative measures, the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) and the Principal Poverty Measure (PPM) (both quasi-relative measures), and consumption-based measures of poverty. Third, we consider approaches to measuring poverty as a continuum or spectrum of well-being (as opposed to a dichotomous measure of whether someone lives in poverty or not). Finally, we conclude the brief by noting the context in which each measure can be applied and describing recent advancements in measurement.

While we focus on poverty as a measure of monetary deprivation, we recognize the importance of other social and economic indicators in capturing diverse experiences of poverty—such as lack of access to education, food, health care, and basic infrastructure—but note that they are beyond the scope of this brief.

I. Major Categories of Poverty Measures, Including Basic Elements

Poverty measures can be generally categorized into two groups: Absolute and relative measures. An absolute poverty measure compares a household’s economic resources against a threshold defined by the cost of minimum necessities such as food, clothing, and shelter. Relative measures of poverty, on the other hand, compare one’s economic resources with a threshold defined by the resources held by others in society—for example, a relative measure that defines poverty status for a given area as having an income less than that area’s median household income.

Absolute and relative poverty measures represent distinct concepts of poverty. In a hypothetical famine—a time during which most of a population is unable to meet their basic needs and therefore lives in absolute poverty—a smaller share of the population might live in relative poverty, depending on where the relative threshold is drawn. In a rich country, where most can afford basic necessities and live above an absolute poverty level, there can be a higher share of the population that lives in relative poverty: These people’s resources would still be far below those held by most others in that country.

Both absolute and relative poverty measures consider the following basic components:

- The economic resources of a household[1]

- A threshold against which these economic resources are compared

There are at least three types of economic resources—income, consumption, and wealth—from which households derive economic well-being. For example, members of a household bring in earnings (income) to pay for housing and food (consumption) and set aside their remaining funds as savings (wealth).

The current U.S. debate around poverty measurement revolves around where to draw poverty lines (thresholds) and how to count economic resources. Our brief focuses on income and consumption as economic resources, and we do not examine wealth, which in the U.S. context is often examined separately from poverty. The broader literature considers absolute and relative measures and the different facets of poverty that each category captures. The most dominant measures used in the United States are absolute poverty, the U.S. government’s official approach, and a hybrid of absolute and relative poverty measurement. In the next section of this brief, we summarize the OPM, examples of relative measures, the SPM (as well as the PPM), and examples of consumption-based measures of poverty. For each measure, we discuss whether it describes absolute or relative poverty, how it sets thresholds and defines resources, what its limitations are, and the circumstances under which it may be suited for use in analysis of poverty.

II. Common Poverty Measures

Official Poverty Measure

The Official Poverty Measure (OPM) is an absolute, income-based measure that has been used to generate the U.S. government’s primary poverty statistics in the United States for more than half a century. The OPM is based on the official poverty thresholds—sometimes referred to as the “federal poverty line” (FPL)[2]—and considers households with annual incomes below these thresholds to be living in poverty. Using this measure, it is relatively easy to compare poverty rates over a long period of time and to estimate populations that are income-eligible for public benefits. The OPM has the following components:

Thresholds

- The original thresholds were based on data from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s: They were calculated as three times the cost of a very minimal basket of foods at a time in which families, on average, spent one third of their after-tax income on food.[3] Thresholds increased with family size and number of children to account for added expenses for additional people, as well as economies of scale. The thresholds have been updated annually to adjust for inflation.

- The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) is used to update the official poverty thresholds. There has been debate over how well the CPI-U corrects for inflation, with some scholars arguing that the CPI-U creates a downward bias and some arguing that it corrects upward.

Economic resources

- In addition to market incomes (e.g., earnings, investment income, pensions, etc.), the OPM counts a limited number of government transfers (mostly in cash), such as Social Security, unemployment insurance, Temporary Assistance to Need Families (TANF), and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

- The OPM counts persons related by birth, marriage, and adoption who are living together in its definition of a family (or a resource unit).[4]

The OPM has several limitations. First, because it is based on the cost of minimal dietary needs identified in the 1960s, its thresholds have not kept up with changes in household spending or modern family life. Households now spend less than 15 percent of their income on food[5] (compared to one third in the 1950s); in contrast, housing, child care, and health care make up a larger share of household spending now than in the past. Second, the OPM excludes some of the largest transfers to lower-income families—notably, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, and (in 2021) the expanded Child Tax Credit. Prior research has additionally counted some of these benefits and compared total household incomes against the OPM thresholds. Third, increases in cohabitation and diverse family structures bring challenges to the OPM, which overlooks the presence of unmarried partners who may share resources with members of the family.

In 2021, the OPM poverty thresholds were $21,831 for a family of one adult and two children and $27,479 for a family of two adults and two children. Based on the OPM thresholds for poverty across all household sizes, 11 million (15.3%) children under age 18 lived in poverty in 2021 (Table 1).

Relative Measures of Income Poverty

Relative measures of income poverty are commonly used in cross-national comparisons of poverty in high-income countries and have some limited use in defining program eligibility in the United States. Such measures compare a household’s economic well-being to that of others in the population, or to a “norm” of economic well-being. They focus on the level of resources that can provide similar opportunities as those available to most other households, as opposed to merely meeting basic needs. Relative measures share

Thresholds

- Relative poverty measures use a threshold based on a percentile of a total population’s income or resource distribution. A conventional relative measure of poverty is defined as having an income below 50 percent of the median income.

- Relative measures automatically adjust for changes in standards of living since their thresholds are based on a percentile of income considered to be representative of the contemporary standard of living.

- Relative measures can account for differences in cost of living across geographies with existing data on local income distributions. In the United States, federal housing and child care assistance programs use relative poverty measures to determine eligibility, as housing and child care costs tend to vary by geography. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Housing Choice Voucher program confers eligibility to families with incomes below half of the local median income.

- To estimate thresholds for use by HUD’s housing programs, the Census Bureau counts incomes reported in the American Community Survey, which include most market incomes (e.g., earnings, interest, retirement incomes), Social Security and SSI benefits, welfare benefits, and unemployment compensation.

Economic resources

- Relative measures typically consider the same type of economic resources (e.g., incomes) to determine both a household’s resources and the threshold against which these resources are compared.

Relative measures also have limitations. Because they consider a household’s income in relation to others’, they cannot capture longer-term change in absolute economic well-being: Material well-being may have improved (in absolute terms) even when relative poverty rates remain the same. This implies that, during an economic downturn, poverty rates based on relative measures may not increase as much as absolute poverty rates typically do if the median income (and thus the threshold) also falls.

In 2021, half of the median household income was about $42,100 for all households with children in the United States. Using this threshold and counting taxes and benefits, one analysis found that roughly 14 percent of children under age 18 lived in households experiencing relative poverty (Table 1).

Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) and Principal Poverty Measure (PPM)

The SPM and PPM incorporate ideas of both absolute and relative measures. In 1995, poverty measurement scholars convened to offer recommendations to address the OPM’s limitations. Drawing on these recommendations, an interagency working group formed to develop the SPM in 2009. Several improvements in poverty measurement have been (and continue to be) made with the SPM. In 2023, at the time of writing this brief, the SPM’s evaluation panel suggested calling the next iteration of the SPM “the Principal Poverty Measure,” given the SPM’s major role in tracking the impact of government programs on poverty. The panel also made new recommendations for future development of the PPM.

Below, we summarize features of the SPM and the panel’s major recommendations for the PPM:

Thresholds

Updating thresholds for the cost of necessities

- SPM: To account for modern levels of spending on necessities, the SPM compares household resources against data on current population-level household expenditures. Specifically, SPM thresholds are set at 83 percent of roughly the median[6] household expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, utilities, telephone, and internet, multiplied by 1.2 to account for additional basic needs.

- PPM: The SPM evaluation panel has recommended that the PPM’s thresholds include the cost of meeting basic health (insurance) and child care needs, and that the basis for the 1.2 multiplier be re-evaluated.

Updating cost of necessities these thresholds would reduce the measure’s quasi-relative nature

- SPM: The SPM is a quasi-relative measure with thresholds based on the distribution of spending across households. This means that the thresholds change over time (as in a relative measure) as spending patterns evolve. However, since household spending on necessities tends to be more stable than incomes, the SPM thresholds can seem similar to permanent, fixed thresholds in an absolute measure like the OPM.

- PPM: The evaluation panel has recommended including basic health and child care needs (as opposed to using a percentile of health and child care expenditures), which will make the future PPM less of a quasi-relative measure.

Better adjusting for housing cost variations

- SPM: SPM thresholds vary by housing tenure—renters, homeowners with mortgages, and homeowners without mortgages—and adjust for geographic variations in the cost of living by accounting for median rents by metropolitan-area status.

- PPM: The evaluation panel has recommended that the PPM eliminate complex adjustment by housing tenure and use fair market rents (FMRs) instead, since FMRs data include more geographies than the median-rent data used for the SPM.

Economic resources

Expanding the definition of household resources

- SPM: In addition to counting cash incomes like the OPM, the SPM counts additional government benefits including tax credits, near-cash (e.g., food stamps), and in-kind benefits (e.g., free and reduced-price school meals).

- PPM: The evaluation panel has recommended that the PPM include health insurance benefits and child care subsidies received in the definition of a household’s resources.

Incorporating a direct account of child care needs

- SPM: The SPM subtracts out necessary expenses to reflect the disposable resources available to a household, including tax liabilities, child care and other work expenses, medical expenses, and child support paid to another household.

- PPM: The evaluation panel has recommended that the PPM directly count child care needs in the thresholds, instead of indirectly as reduced resources to a household.

Expanding the definitions of household members

- SPM: Compared to the OPM, the SPM accounts for additional household members who share housing, food, and other living expenses, including unmarried partners, unrelated children, and their relatives in the household.

- PPM: The evaluation panel has recommended that the PPM count all related and unrelated individuals in a household, because housing—the largest consumption item—is shared among all members of a household.

Because the SPM uses expenditures data that have a relatively short history, poverty measurement scholars have developed techniques to examine long-term trends in SPM poverty rates.[7] Scholars have taken different approaches to this task and long-term poverty trends vary based on the method used. Some approaches anchor thresholds to household expenditures from a (recent) point in time while others use partial historical data to form historical thresholds; both adjust these reference data for inflation for years when data were not collected. There has not yet been discussion around how well the PPM can trace historical trends since it is still under development; however, because it is likely to require new data (e.g., on the cost of a basic health insurance plan), there may be some limitations for the purpose of historical analysis.

In 2021, the average SPM thresholds across the country for two adults and two children were $31,107 for homeowners with mortgages, $26,279 for owners without mortgages, and $31,453 for renters. SPM-based poverty rates were lower in 2021 than before the COVID-19 pandemic,[8] primarily due to temporary policies such as Economic Impact Payments (or “stimulus checks”), expanded unemployment benefits, and the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit. Around 3.8 million children under age 18 (or 5.2%) lived in poverty as measured with the SPM in 2021 (Table 1); in 2020, 9.7 percent of children lived in SPM-based poverty.

Consumption Poverty Measures

The poverty measures described above largely consider a household’s income in defining its economic resources. Consumption poverty measures, by contrast, consider that a household’s economic well-being is reflected in its consumption. This approach is rooted in an economic theory that households draw on resources (incomes, savings, assets, etc.) to support their economic well-being and save those resources when they are not in need. Households’ consumption patterns do not change as sharply as their incomes, either over short periods of time (e.g., an economic downturn) or over the life course (e.g., through aging and retirement). Therefore, from this perspective, it is insufficient to use income data to define economic resources, as in the OPM and SPM.

Consumption poverty measures, like their income-based counterparts, can be either relative or absolute. We summarize key components of consumption-based measures from this National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) report.

Thresholds

- The consumption relative poverty measure sets the threshold at half of the median value of consumption among all households.

- The consumption absolute poverty measure uses the thresholds that yield consumption-based poverty rates that are the same as OPM-based poverty rates in the baseline year (e.g., 1980). Consumption absolute poverty rates can be interpreted as the prevalence of consumption poverty today based on a fixed level of consumption (of an OPM-poor household in the baseline year).

Economic resources

- Economic resources in consumption measures of poverty include easily measured components of consumption, such as food, rent, and utilities. Data on these items are drawn directly from the Consumer Expenditure Survey. A value of current consumption of durable goods (e.g., a house or vehicle) and health insurance is estimated as part of total resources because payments for these items (for example, mortgage payments) do not accurately capture the value of current consumption. By using expenditures data, the consumption poverty measures also address bias in reports of household incomes, as measurement issues have been identified in the income data used in the OPM and SPM (e.g., underreporting of public benefits and self-employment incomes).

Although consumption poverty measures are grounded in theory, they also have a few limitations. For example, consumption measures do not differentiate whether households finance consumption with high-interest payday loans or in other ways that compromise their well-being. These measures require complex calculations of the value of consumption derived from certain goods and services and use expenditures data that are available only for large geographic areas. It is also more difficult to identify the effects of income policies on consumption poverty than on income poverty.

There is no single, universally agreed-upon method for determining consumption poverty, and no method is considered “official” by the federal government. One study found that estimates for consumption-based absolute poverty rates ranged from 16.3 percent to 19.5 percent among children, with thresholds (anchored to the official poverty level in 2015) of $26,583 for a family of four in 2018.

III. Poverty as a Continuum of Experience

While both absolute and relative poverty measures group people into one of two categories—as either living in poverty or not—an income just slightly above the threshold may not provide a noticeable advantage in economic well-being over an income that is slightly below the threshold. In conceptualizing poverty as a continuum of experience, poverty scholars use different percentage multiples of poverty thresholds to capture varying levels of economic scarcity. Both relative and absolute poverty measures can be adapted for this purpose:

- With relative measures, levels of poverty can be measured by using different references to the income or consumption distribution as a threshold (such as 60% or 80% of the median income).

- With absolute measures, the continuum of experience can be captured by using income-to-needs ratios. For example, a ratio of a household’s income to the official poverty threshold (e.g., a value of 1.2 means that family income is 1.2 times the poverty threshold) is commonly used to capture the range of experiences of economic well-being (as in this study). Different cutoffs are also frequently used in statistical reporting, including 100-200 percent of the threshold for low-income status and less than 50 percent of the threshold for deep poverty.

Another way to evaluate the depth of poverty along a continuum is to use the concept of a “poverty gap.” Poverty gaps can be used to answer questions about the amount of income needed to lift a household out of poverty. Related measures include (but are not limited to): (1) the total poverty gap—that is, the total amount of gaps between each household’s income and the poverty line across all poor households; and (2) the poverty gap index, or the average ratio of the shortfall in income from a poverty line to the poverty line.[9] For two economies with similar poverty rates, one may have a larger poverty gap than the other, indicating a higher level of economic need.

IV. Using Appropriate Measures to Best Understand Poverty

The measures reviewed in this brief define economic deprivation differently, from absolute to relative terms, and each considers a distinct level and makeup of economic resources sufficient for living in the United States and adjusts for temporal and geographic differences to varying degrees.

Each measure has its own strengths and limitations.

- The OPM is an absolute poverty measure based on the cost of a minimal diet in the 1960s. The OPM-based official poverty rates are suited for analysis of cash transfers and of long-term trends. However, for the most part, its thresholds based on living standards from more than a half century ago do not reflect the needs of modern life.

- Compared to absolute measures, relative measures—by referencing median incomes—focus on whether a household or other unit of analysis has economic resources that more closely resemble the resources available to the majority or middle class in society. With this reference, relative measures adjust for changing standards of living more effectively than other measures but cannot measure improvement in absolute economic well-being over time.

- The SPM and PPM are quasi-relative measures that consider increasingly important factors that affect economic well-being, including government in-kind and tax benefit transfers and geographic differences in housing costs. However, these measures have a relatively short history of data to fully capture longer-term trends, and the adjustment for health and child care needs is still in development.

- Consumption poverty measures address underreporting of incomes and consider drawing on resources in addition to incomes for consumption; however, these measures use expenditures data—some of which require additional estimation of consumption and/or are unavailable for smaller geographies.

Because each measure involves tradeoffs between their strengths and limitations, their appropriate use depends on context and application. For example, the OPM may still be suited for historical comparisons, but the SPM (or PPM) and relative measures may be more ideal measures to center on today’s needs. Consumption poverty measures may provide information about aspects of material well-being that income-based measures do not fully capture. With evidence from multiple poverty measures across studies, policymakers and researchers can better understand different aspects of poverty and the impacts of policy on poverty.

Recent or future developments can further improve poverty measurement. For example, poverty scholars are working to sharpen their estimation for child care cost and health insurance value, validate poverty measures with hardship indicators such as food insecurity, and use monthly poverty measures to capture instability in economic well-being. New data applications may also address the unique limitations in each measure. For example, the use of administrative income data helps reduce bias in income reporting, and credit card data offer timely information on consumption. Continued advancement in poverty measurement will help policymakers, practitioners, and informed citizens better understand poverty—through multiple lenses and through effective measurement—as we all work toward reducing it.

Footnotes

[1] A family or an individual can also be an economic unit that makes economic decisions; however, in this brief, we refer to households, which are the unit of analysis for most major poverty measures in the United States.

[2] Although the term federal poverty line (FPL) is frequently used in the literature, it is ambiguous and can mean either of the two different sets of income cutoffs—the federal poverty thresholds used by the Census Bureau for statistical purposes and the federal poverty “guidelines” used by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to administer programs. The federal poverty guidelines are a slightly different version of the federal poverty thresholds to determine program eligibility for benefits (see here for a list of government programs that use the guidelines). In Alaska and Hawaii, the guidelines are much higher than the thresholds to adjust for these states’ higher cost of living.

[3] The average household in the 1950s spent one third of its income on food. However, in any year, low-income households typically spend a higher share of household income on food than the average household.

[4] Which members of a household (or another resource unit) are counted in a poverty measure affects not only the resources available to a household but also their needs (and therefore the measure’s thresholds). However, because explaining the calculation of thresholds based on the composition of a resource unit requires technical details (due to economies of scale), we discuss the implications of defining the resource unit under the section for household economic resources.

[5] Specifically, households with incomes in the middle quintile spent about 12 percent of their incomes on food in 2021.

[6] In 2019, the SPM interagency technical working group revised the base of thresholds from averages within the 30th to 36th percentile of household expenditures to 83 percent of the averages within the 47th to 53rd percentile range.

[7] The Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy has made historical SPM data dating back to 1967 publicly available online.

[8] In 2019, the SPM-based poverty rate among children under age 18 was 12.7 percent and the OPM poverty rate was 14.4 percent. The SPM poverty rate declined to 9.7 percent in 2020 in part due to two rounds of Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) during the first calendar year of the pandemic, and dropped again to 5.2 percent in 2021 due to the last round of EIPs and the temporarily expanded, fully refundable Child Tax Credit. In contrast, the OPM poverty rate increased to 16.0 percent in 2020 before declining to 15.3 percent in 2021.

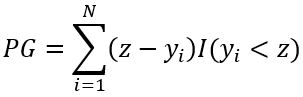

[9] Mathematically, the total poverty gap (PG) can be expressed as  , where z denotes the poverty threshold, yi: each household’s income; N: the total number of households;

, where z denotes the poverty threshold, yi: each household’s income; N: the total number of households; ![]() equals one if a household’s income is less than the poverty threshold and zero otherwise. The poverty gap index (PGI) can be calculated as

equals one if a household’s income is less than the poverty threshold and zero otherwise. The poverty gap index (PGI) can be calculated as![]() . Consider a scenario in which there are only three households: Each has a household income of $20, $10, and $45, respectively, and the poverty threshold is identical, $30, for all households. The total poverty gap for this population would be ($30-$20)+($30-$10)=$30, and the poverty gap index would be

. Consider a scenario in which there are only three households: Each has a household income of $20, $10, and $45, respectively, and the poverty threshold is identical, $30, for all households. The total poverty gap for this population would be ($30-$20)+($30-$10)=$30, and the poverty gap index would be![]() .

.

Suggested Citation

Chen, Y., Fuller, J., & Ryberg, R. (2023). Knowing the strengths and limitations of poverty measures can help us better understand poverty. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/6813u6201t

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram