More than one fifth of all college students are parents, who may be at risk of being pushed out of school by a system not designed to accommodate their needs. Parenting students often earn higher GPAs than their classmates without children, but are less likely to complete their degrees. Less than one third of mothers obtain a degree or certificate within six years of enrollment.

When parenting students have the support they need to attend to their studies, they create opportunities for themselves, their children, and society at large. Single mother students who finish their degrees have higher lifetime earnings and contribute more in taxes throughout their lifetimes than those who do not finish. For every dollar invested in services that support single mothers in school, the United States would get back approximately $5 in increased tax contributions and decreased reliance on public assistance. Parents with higher levels of education also pass on many benefits to their children, spanning educational, health, and behavioral outcomes.

This brief examines young student parents ages 18 to 24: who they are, what types of postsecondary institutions they attend, and how those schools support them with on-campus child care, employment opportunities, flexible schedules, and academic/career counseling services. We find that:

- Many young parents attend community colleges, and young parents are more likely than their childless peers to attend for-profit schools.

- Public schools—both four-year and community colleges—tend to offer more supports relevant to parenting students than private schools (especially for-profits).

- While more work is needed to understand whether parenting students have access to these services and how effective they are for students, it is clear that higher education has an opportunity to better support parenting students and improve the lives of these students and their children.

Parenting students are mostly female and students of color.

More is known about parenting students of all ages than about young parents in particular. For example:

- Seventy (70) percent of all parenting students are women, and 62 percent of these women are single mothers.

- Fifty three (53) percent of all student parents have a child under age 6 who likely require child care arrangements while their parents are at school or work.

- Parenting students are disproportionately first-generation college students, many with low incomes.

- The majority (51%) of parenting students are students of color.

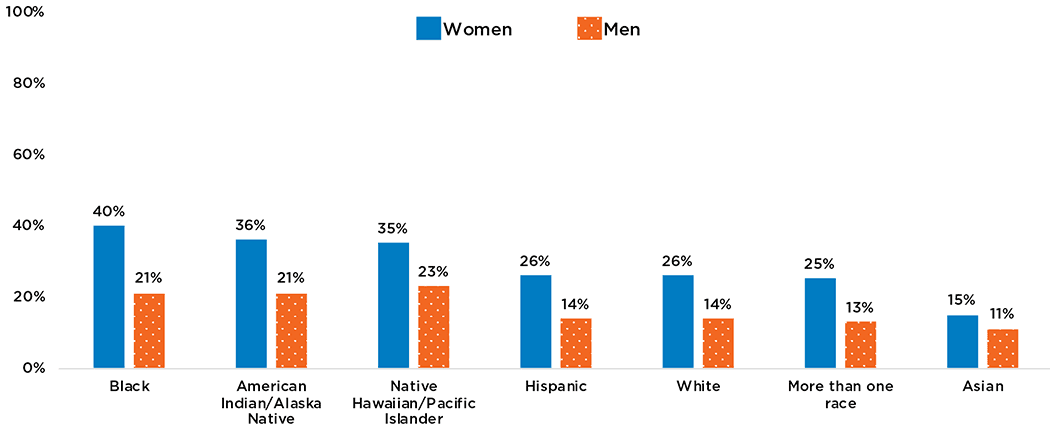

- Forty (40) percent of Black female college students are mothers, as are 36 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native female students and 36 percent of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander female students (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. More than one fifth of college students are parents with significant variation by race and ethnicity

Download

Source: IWPR analysis of data from NPSAS:16. Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) and Ascend at the Aspen Institute. (2019). Parents in college by the numbers. https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/C481_Parents-in-College-By-the-Numbers-Aspen-Ascend-and-IWPR.pdf

Narrowing our focus from parenting students of all ages to young parents, 14 percent of young parents ages 18 to 24 were enrolled in higher education at some point in the previous three months in 2018.[1] Young parents who identify as Asian, Black, other races (e.g., not white, Black, AI/AN, Asian, or Pacific Islander), or multiple races had the highest enrollment rates at 18 percent, 17 percent, 17 percent, and 16 percent, respectively.

Young parenting students often attend community colleges and are disproportionately likely to attend for-profit institutions.

Like all college students, young parenting students are limited in their choices of colleges to attend, based on logistical factors such as affordability and geographic constraints. But parenting students may have additional considerations that may constrain their choices when selecting where to go to school.

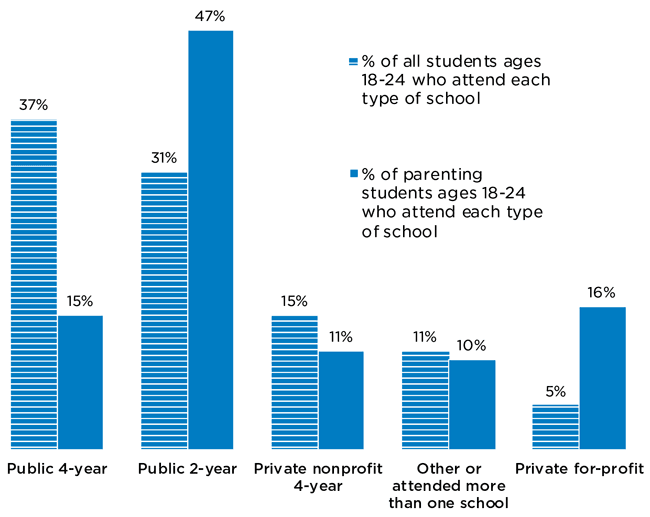

Nearly half (47%) of young parenting students attended community colleges during the 2015-16 school year.[2] About one quarter (26%) of young parenting students attended four-year schools, with slightly more attending public institutions than private nonprofit institutions (15% and 11%, respectively); a significant minority of young parents attended private for-profit schools, at 16 percent.

Figure 2. Young parenting students disproportionately attend community colleges and for-profit institutions

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:16)

This distribution of institutions is similar to that among parenting students of all ages, but is quite different from the distribution seen among all young students. Among all young students, the largest proportion (37%) attended public four-year schools, while the largest proportion of young students with children attended community colleges. At the same time, just 5 percent of all young students attended a for-profit college, compared to 16 percent of young parenting students.

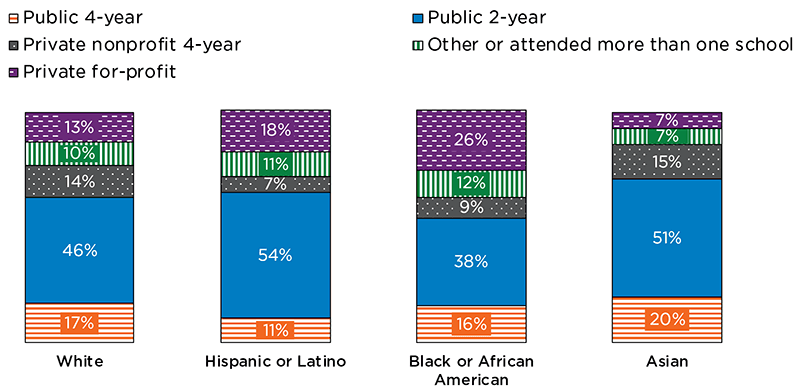

The types of colleges that young parents attend vary substantially by race and ethnicity. More than half of young Hispanic students with children attend community colleges, reflecting the large proportion of Hispanic students that attend community colleges in general; these institutions are more affordable and may allow a balance of education with work and family obligations. Both Black and Hispanic parenting students are more likely to attend for-profit schools that may profit off of students of color, relative to their peers of the same race or ethnicity without children and to white parenting students. Notably, more than one quarter of young Black parenting students attend private for-profit colleges—more than the number who attend public or private nonprofit four-year institutions combined.

Because more than one third of Black and American Indian/Alaska Native female students are parenting, we present a special focus on Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) below.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are colleges and universities established before 1964 to provide educational opportunities to Black Americans. There were 101 HBCUs in the United States in 2018, and these institutions can be publicly or privately run. Less than 5 percent of young Black parenting students attend HBCUs.

Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) were established in the late 1960s to serve the higher educational needs of American Indian people. There are currently 34 TCUs in the United States, located primarily in the Midwest and Southwest. All TCUs began as two-year colleges and many have open admissions policies. Many are located on reservations that are geographically isolated from other institutions of higher education. A 2019 non-representative survey found that almost half of the students surveyed at TCUs were parents.

Figure 3. More than one quarter of young Black parenting students attend for-profit institutions, while more than half of young Hispanic parenting students attend community colleges

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:16)

Schools differ in their abilities to fully support their students, based on a tension between the resources they have and the needs of the populations they serve; this tension can lead to large differences in graduation rates. Community colleges tend to be more affordable and accessible, with open admissions policies. But they are also chronically under-resourced, and just 30 percent[4] of all students graduate with a two-year degree within three years. Four-year public and nonprofit colleges tend to be less accessible, with stricter admission policies and higher costs, but are better resourced and have higher graduation rates. Fifty-eight percent of students at public four-year colleges graduate within six years, on average, compared with 67 percent at private nonprofit colleges. The graduation rates at for-profit schools fall between those of community colleges and four-year schools: 35 percent of students graduate at four-year for-profit institutions within six years, while 63 percent of students graduate within three years at for-profit two-year institutions.

Public colleges and universities offer more services than private schools—especially compared to private for-profit schools.

A non-representative national survey from Fall 2019 found that nearly half of responding parenting students felt either somewhat or very disconnected from their campus communities, and approximately one third of respondents did not see family-friendly characteristics on their campuses. Another 2019 survey of a convenience sample of parenting students found that more than half of parenting student respondents were food insecure in the past month, and more than two thirds were housing insecure in the previous year.

Colleges can support their parenting students by offering services tailored to their needs and experiences. Below, we examine four types of supports for which data are available on colleges across the nation: on-campus child care, academic and career counseling services, employment services, and flexible course schedules. The data reported below show whether institutions report providing a service[3]; unfortunately, information is not available on the services’ cost to students, their quality, or whether they are implemented in a way that meets parenting students’ needs.

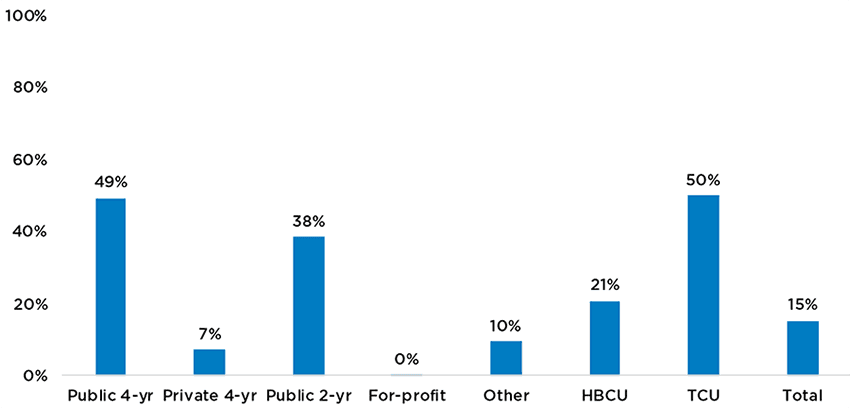

On-campus child care. Child care and its associated costs represent a significant hurdle for parenting students. However, the prevalence of on-campus child care has been in decline since at least 2002. According to a 2019 survey of parenting students, just 8 percent of respondents used on-campus child care. At the institution level, just 15 percent of colleges reported offering on-campus child care for students’ children in 2019. Public colleges led the way in providing on-campus child care, with 49 percent of four-year colleges and 38 percent of two-year colleges offering this service. In contrast, less than 1 percent of for-profit institutions reported offering on-campus child care. A larger proportion of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) offered on-campus child care than non-HBCU and non-TCUs, respectively. Existing data do not provide information on how many child care slots are available for students’ children relative to those of faculty, staff, or community members, or how affordable this service is for students.

Figure 4. Percentage of colleges that offer on-campus child care for students’ children

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2019-2020

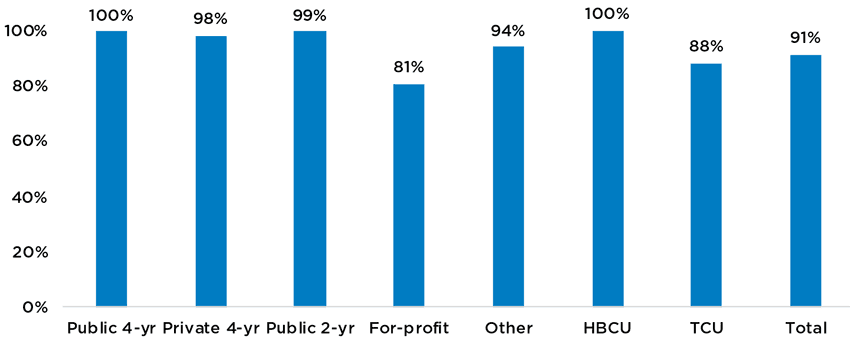

Academic/career counseling. The vast majority of colleges offered some form of academic or career counseling services, at 91 percent. However, these services were less common at private for-profit schools, with 81 percent offering these services. All HBCUs offered these services, as did 88 percent of TCUs.

Figure 5. Percentage of colleges that offer academic/career counseling services

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2019-2020

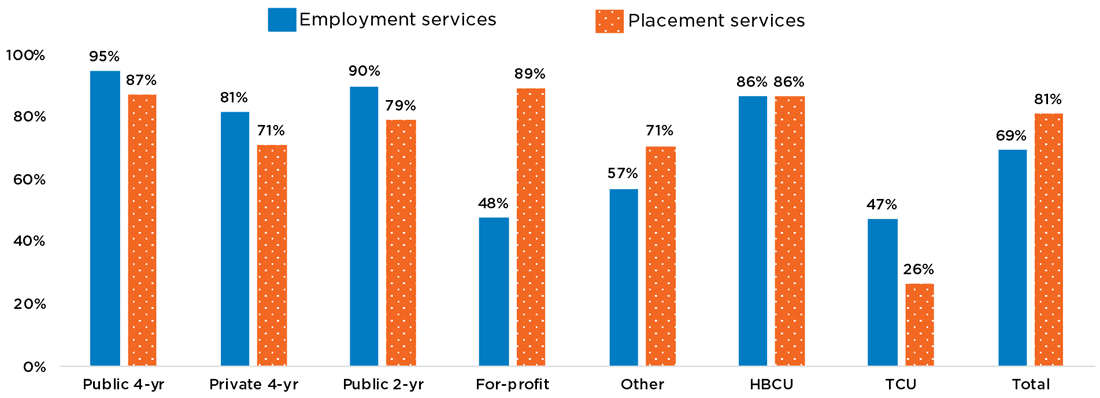

Employment services. Employment services are important to help students find jobs—both while in school and after graduation. Just over two thirds of schools offered employment services for current students. Public schools again led the way, with 95 percent of four-year colleges and 90 percent of two-year colleges offering employment services. Eighty-one percent of private nonprofit schools have employment services, but less than half of private for-profit schools offered them. Most for-profit schools (89%) tend to focus their efforts on placement services for graduates.

A higher proportion of HBCUs than non-HBCUs offered both employment services for current students and placement services for graduates. Meanwhile, fewer TCUs offered either of these services than other types of schools. About one half offered employment services for current students and about one quarter offered placement services for graduates.

Figure 6. Percentage of colleges that offer employment services for current students and job placement services for graduates.

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2019-2020

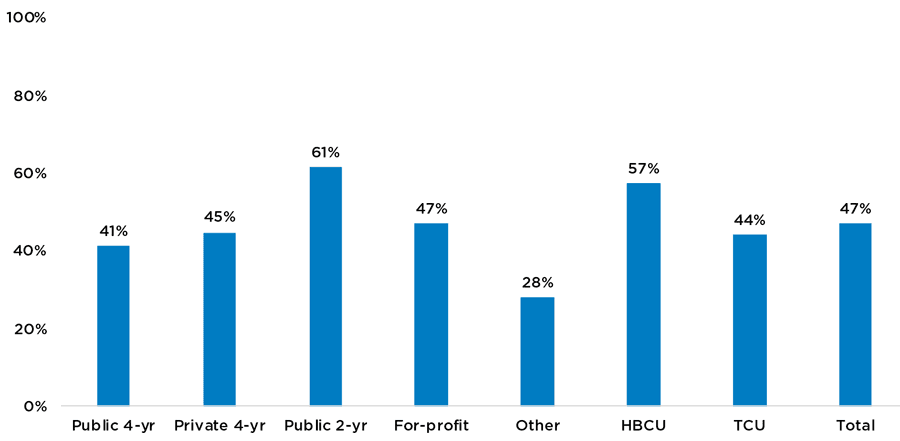

Flexible schedules. Just under half of all colleges offered weekend and/or evening college in which a student can take a complete course of study only on weekends or the evenings. These offerings were more common at community colleges and HBCUs.

Figure 7. Percentage of colleges that offer flexible schedules

Source: Child Trends’ analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2019-2020

Conclusions

By gaining an understanding of who parenting students are, which schools they attend, and which services those schools do or do not provide, higher education institutions can more effectively allocate resources and better support parenting students. Institutions of all kinds have an opportunity to provide greater support for their parenting students, but this shift is likely to look different depending on the type of institution. Many institutions may benefit from additional funding to bolster their supports. Other schools may need to better advertise and tailor their resources to recruit and retain parenting students. Community colleges are accessible to parenting students and offer a relatively high number of support services, but these schools are more likely to serve students who need additional supports and are often chronically under-resourced; this frequently leads to low completion rates. Four-year public and private schools have higher graduation rates but are less accessible and affordable for parenting students. Furthermore, young parenting students are more likely to attend for-profit schools that offer fewer services and are much more costly than community colleges, despite the fact that they do not lead to better career outcomes.

Of course, it is not enough to simply offer services. They must also be accessible to parenting students. More work is needed to understand whether parenting students have access to the services that institutions offer, the effectiveness of those supports, and how they can be tailored toward students’ needs. A first step toward this understanding is for colleges to collect better data on their parenting students.

Further, it is critical to address the needs of student parents to begin to address racial and ethnic equity in higher education at large. Due to a myriad of structural challenges, less than half of all American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Black students graduate with a bachelor’s degree within six years. Meanwhile, more than half of Hispanic students (53%) do so, as do 64 percent of white students and 74 percent of Asian students. Supporting student parents will contribute to narrowing racial and ethnic disparities in higher education outcomes, since Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander mothers make up a large proportion of parenting students.

By supporting parenting students, higher education institutions have an opportunity to improve the futures of not only parenting students, but of their children as well. The sooner that young parents graduate with a high-quality degree, the sooner that they, their families, and society as a whole will start to reap the benefits.

Download

References

[1] Enrollment rates are based on Child Trends’ calculations using the one-year 2018 American Community Survey. IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

[2] We use community colleges as a shorthand to refer to public two-year colleges. The highest degree that these schools offer is a two-year degree. Some community colleges offer bachelor’s degrees and are not included in this category.

[3] About 5 percent of four-year public institutions are missing data on support services, largely because system offices responded to IPEDS for the state public institutions.

[4] Graduation rates are based on Child Trends’ calculations using the IPEDS Trend Generator: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/build-table/7/19?rid=59

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram