Toolkit for Improving Family Planning Services in School Settings

Health Resource Center Coordinators Support Care Through Relationship Building, Health Education, and Warm Referrals

To address adolescents’ health needs in schools that do not have school-based health centers, AccessMatters, the Title X grantee for southeastern Pennsylvania, developed the Health Resource Center (HRC) model—a school-based model of care that, for more than 30 years, has leveraged its skilled network of family planning providers to support students to navigate existing health care settings in their neighborhoods and communities and bring health care resources into area schools. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), a member of AccessMatters’ Title X network, coordinates five HRCs in Philadelphia schools. Key roles of HRC coordinators include creating a safe space for youth to learn about sexual health, forming trusting relationships with young people and the school community, and providing referrals.

As a part of AccessMatters’ program, CHOP runs HRCs in five Philadelphia schools with demonstrated need for expanded sexual and reproductive health care access.[1] CHOP and AccessMatters work flexibly with each school to assign an HRC coordinator and then to determine the hours, location, and role of the HRC coordinator. This ensures that in each selected school an HRC coordinator is present for an established number of hours per week but with variability in the structure for each school. During their time in the schools, each coordinator is responsible for:

- Reproductive health counseling

- Pregnancy and STI testing (if offered)

- Condom distribution

- Formal and informal health education (e.g., classroom presentations or conversations in the hallway)

- Partnerships with the school nurse, counselor, or other school officials

- Referrals to outside clinics for ongoing care that cannot be met in the school itself (e.g., STI treatment, prenatal care, or prescriptions for contraceptives or other medications)

The coordinator also works to become a member of the school community—attending orientations, sporting events, or assemblies when possible. The CHOP HRC coordinators have typically been nurses or medical assistants (MAs) who currently or previously have worked in CHOP clinics. Health educators who work in other HRCs associated with AccessMatters also serve in this role but are not included in this study.

This case study describes key lessons CHOP has learned from coordinating its HRC program and is based on interviews with CHOP’s HRC staff and one AccessMatters staff member. It describes the AccessMatters HRC program’s background and context, what program implementation looks like in practice at CHOP, and the ways in which the HRC program reflects the four foundational approaches that we maintain are integral to providing high-quality family planning and sexual health services to youth. The case study also provides recommendations and resources for programs interested in learning more about this model of care.

Background and Context

In response to high rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), AccessMatters—a Philadelphia-based sexual and reproductive health organization—developed the Health Resource Center (HRC) Program in 1991. AccessMatters started the program and still manages all contracts in partnership with the School District of Philadelphia through funding from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The program still manages the contract with the School District of Philadelphia that permits the HRCs to operate and defines their general scope of work. The program’s initial goal was to prevent teen pregnancy; it began primarily as a condom distribution and counseling program in five schools in 1992 but expanded over the years to additional sites across the School District of Philadelphia.[2] Schools have participated in and left the program over time based on the changing needs of their student bodies and district and school priorities. Current funding for the program comes from the Pennsylvania Department of Health and the Title X program, which is part of the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The original purpose of the program was to create service centers to provide confidential, nonjudgmental counseling and condom distribution in several schools across the School District of Philadelphia. This would, in turn, prevent teen pregnancies and STIs by meeting teenagers where they were (literally, at school) and supporting them in safe and nonjudgmental ways to make informed decisions about whether to engage in sexuality activity and—for youth who were sexually active—offering strategies for reducing their risks of unplanned pregnancy, STIs, and other potential adverse health outcomes.

Since the program began more than three decades ago, the HRCs have grown and changed with the needs of the communities they serve and in sync with a changing understanding of adolescent development. Although the HRC program’s core values have stayed the same, services have expanded in response to the changing needs of the schools and communities. Over the last 30 years, the in-school work of HRC coordinators has evolved and now focuses more on supporting youth to identify their own health goals. They do this through formal presentations to classrooms, sports teams, or in assemblies and through one-on-one conversations with students informally (in the hallway) and formally (counseling sessions in their office). Goal setting might include preventing a pregnancy or, for a much smaller group of students, potentially planning a healthy pregnancy. Being in the schools to interact with students where they are helps coordinators create relationships so they can focus on preventing STIs and unintended pregnancies (the majority of teen pregnancies). Promising analyses from AccessMatters, in their report The Impact of Health Resource Centers, point to the fact that zip codes with HRCs have seen declines in teen birth rates, chlamydia, and gonorrhea greater than those seen nationally or in other Philadelphia zip codes.

HRC Coordinators

A key component of the model is the HRC coordinator who works in each school that participates in the program. This coordinator is responsible for:

Providing medically accurate health education and counseling services in the school

Testing for pregnancy and STIs (if the school offers it)

Condom distribution

Partnering with school staff to ensure students receive needed services (i.e., school nurse or counselor, teachers, coaches)

Outreach to students (e.g., through health campaigns, classroom presentations, presentations to teams or clubs, or schoolwide announcements)

Supporting and helping students navigate referrals to care in outside clinics

Since the coordinator’s role is shaped by the needs and space available in schools, each coordinator creates their own structure in their program site. In some schools, the coordinator sets up a specific space in the nurse’s suite or in another office suite. In other schools, the coordinator uses a mobile resource cart but can also use the nurse’s office for counseling or testing as needed. Some coordinators are at their school every day, while others have a set schedule that has them in the school, on average, two afternoons each week. Regardless of schedule, every coordinator seeks to integrate into the school community—by working with teachers or coaches on presentations; conducting health presentations to classes; leading health campaigns with posters or announcements in the school; sitting in the cafeteria at lunch time and talking with students; adopting an open-door policy that encourages students to bring questions or concerns; or coordinating with the nurse, school counselor, or other adults to ensure a high level of care regardless of whom a student initially approaches with their health needs. While outreach is done throughout the school, some students first see the school nurse who then sends them to the HRC coordinator depending on their needs (i.e., contraceptive counseling or pregnancy testing).

Following are examples of scenarios in which a student might interact with the HRC:

A sexually active student comes into the HRC with detailed questions about STIs. After further conversation, the coordinator learns that the student has just found out that their partner has chlamydia. The coordinator can screen the student for the infection and follow up to ensure that the student receives test results and is linked to treatment, if necessary, for the student and any partners.

A student visits the school nurse with nausea, and after a brief sexual history interview, it is revealed that the student has had unprotected sex at least once, putting the student at risk for pregnancy. Because of the partnership between the nurse’s office and the HRC, when the nurse identifies a pregnancy concern, they can seamlessly refer the student to the HRC. The coordinator administers a pregnancy test, ensures that the student receives the test results, and then refers the student to a Title X clinic if contraceptive services or prenatal care are needed.

HRC coordinators present to the football team about STIs and symptoms of concern. Football players, their friends, or sexual partners might then come with follow-up questions or to get tested.

AccessMatters provides all HRC coordinators with comprehensive training and professional development through in-person, live, and asynchronous remote opportunities. The topics covered in these trainings include contraceptive counseling, supporting students’ goal setting (e.g., through motivational interviewing), updates on standard of care for different STIs or prenatal care, gender identity, healthy relationships, consent, and health and racial equity. Currently, each CHOP HRC coordinator is also trained as a nurse or MA, although people with health educator training or certification serve as coordinators in other AccessMatters’ HRCs. Coordinators are selected based on their interest, their experience working with adolescents, their connection to the communities, and their flexibility in terms of scheduling. The program director at CHOP, a nurse practitioner, works to identify people with interest and regularly searches for additional staff. While each coordinator is a CHOP employee, not all of them maintain clinical responsibilities. At the time of publication, two coordinators served full time in the schools while one also covered time in one of the CHOP clinics. Each of the coordinators introduces themselves as a CHOP employee and explains to students that they can help them navigate the clinic or doctor’s appointments, including helping them schedule and get to appointments.

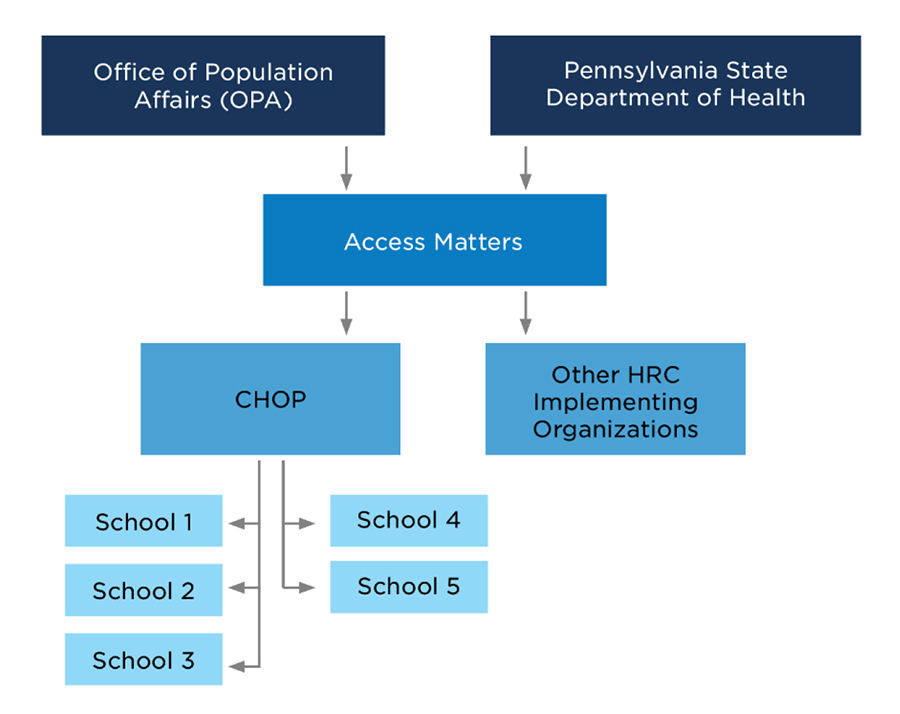

Figure 1 shows the key actors in this model. The two funders are shown at the top. They both fund AccessMatters, which awards sub-grants to CHOP and other implementing organizations. Then each implementing organization supports schools: currently five schools in CHOP’s case.

Figure 1: Key Actors in AccessMatters’ Health Resource Center Program

AccessMatters’ HRC Program Draws on Four Foundational Approaches

Child Trends identified four approaches as integral to effectively providing family planning and sexual health services to youth in school-based settings. We believe the AccessMatters/CHOP HRC program exemplifies these four foundational approaches, which are: 1) embedding equity, 2) prioritizing adolescent-friendly care, 3) maximizing outreach and access, and 4) leveraging partnerships. For a detailed description of our four foundational approaches, visit the Foundational Approaches section of this toolkit. This section of the case study highlights how the Philadelphia HRCs have clearly integrated factors from these four approaches into their work.

Embedding equity

Equity is front and center to the HRC program’s work from addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health care to ensuring that students of all sexual orientations and gender identities are treated with compassion and respect. We observed HRC coordinators employing the following five equity practices:

Prioritize conversations and skill development on equity-related issues from the first HRC coordinator training sessions. AccessMatters provides trainings on client-centered inclusive and affirming care, including raising awareness of personal implicit biases and systemic oppression, which prepares them to work with students of all races, ethnicities, gender identities, and sexual orientations.

Create an inclusive environment in the HRC itself. One coordinator makes inclusivity clear from the signs she displays: “I have this sign … it says, ‘all are welcome.’ It doesn’t matter if you are the most popular kids, if you’re the nerdiest kids or have a disability, everyone is welcome [in the HRC].” Coordinators can be clearly inclusive in their signage and actions to ensure that students know they do not have to be or act a certain way for the HRC to serve them or for the HRC to be a helpful resource.

Help students learn to be self-advocates, especially in the context of a health care system that does not often produce equitable outcomes for people of color. Each coordinator spoke about how they work to empower students’ confidence in standing up for their own preferences, asking questions, and feeling good about their own medical decisions. One coordinator mentioned the challenge of finding the balance between educating students about what to expect in a clinic visit, to be aware of racial biases, and how to handle such situations. She shared her challenge with talking about these topics in a way that does not completely discourage students from seeking care because “Now it’s like, I’m not going back to the doctor because you know, they’re gonna try to convince me to do something [that] maybe I don’t wanna do.’ And then that cycle continues … and so it’s tough. It’s really tough.” This coordinator tries to be very clear about what a student can expect from a visit and to clarify that she is available to discuss the visit afterwards if needed.

Incorporate non-directive counseling. One coordinator spoke about “put[ting] aside their own moral views” and supporting students’ own goals. For example, instead of assuming that a student does not (or should not) want to be pregnant, HRC coordinators ask youth what their pregnancy plans were. If the student’s preference is to continue with a pregnancy, coordinators provide access to resources such as prenatal care. This non-directive counseling aligns with Title X recommendations on asking questions related to family planning, rather than making assumptions that might be based on age or other demographic factors.

Be open on topics of gender identity and sexual orientation. HRC coordinators spoke about being open-minded and inclusive when asking about sexual behaviors. For example, one coordinator tries to ask each student about the genders of their sexual partners rather than assuming or accidentally referring, for example, to a male partner for a female student. This approach promotes equity by creating a space in which all students can have open conversations and receive education on any types of sexual behaviors. Similarly, HRC coordinators mentioned that they cannot assume that all sexually active female students are at risk of pregnancy but emphasized that physical and emotional safety in sexual partnerships is important for all youth.

Prioritizing adolescent-friendly care

HRCs can be adolescent-friendly by referring students to safe and supportive clinic partners through what are known as warm handoffs. In the context of these handoffs, or referrals, to other services, “warm” means ensuring that the student knows where to go, what the process will be like, and who they will be seeing (if known) and reminding them that they can always come back to the HRC with questions or if they need support from an advocate. Student safety, location of the clinic, and adolescent-friendly providers are prioritized over whether the clinic has connections to CHOP.

HRC coordinators create safe spaces by spending time creating trusting relationships. This is adolescent- friendly because it creates space to meet adolescents where they are physically (in school) and emotionally. They attend events at the school, focus on learning students’ names and saying hello in the hallways, and present themselves as a calm adult who can answer questions about a variety of concerns. They also focus explicitly on confidentiality, with the caveat that they are mandatory reporters which means they are legally required to report certain situations that might be illegal or harmful to young people. For many adolescents, a sexual health visit is one of the first times they experience a visit with a health care professional on their own. One coordinator tries to create space for a confidential conversation by letting youth know explicitly that “whatever [is] said between [the two of us], it’s going to stay with me.” This confidentiality allows students to ask questions that they may view as embarrassing, private, or scary. Coordinators encourage students to speak with their parents or caregivers, but recognize that, for some young people, this may not be possible or safe. In this way, HRCs not only teach students about safety, respect, and confidentiality, but they also model a positive interaction with a health care professional. In this way, they teach students what they should be able to expect from health care providers in terms of the interactions and supports they should receive and the agency they should feel in doing so.

Maximizing outreach and access

Coordinators also use their strong relationships with students to conduct outreach and increase use of the HRC. One coordinator stated that, while sexual health is part of this relationship building, getting to know students at the personal level builds the kind of trusting partnership that allows students to come to the HRC and ask questions about sexual health. She said, “You get to know the kids, and you have a rapport, and they just look to you for more than just reproductive and sexual health.”

One way that HRC coordinators begin to foster relationships with students is by physically placing themselves in areas with high student traffic such as a courtyard or hallway. This way, coordinators can answer casual questions or continue to build rapport while also referring students to a private space as needed. HRC coordinators also advertise health initiatives across the school. To promote the many services that HRCs offer, AccessMatters provides coordinators with a series of monthly campaigns on specific health topics. The coordinators can use the themes and materials from AccessMatters to create interactive outreach activities that draw students’ attention to the HRC.

Leveraging partnerships

The partnership between CHOP and AccessMatters is grounded in the contract they hold with the School District of Philadelphia. To ensure timely and effective implementation, AccessMatters provides funding, training, and ongoing support while CHOP implements and manages their five HRCs day-to-day. AccessMatters and CHOP work closely to ensure that HRCs run efficiently and effectively and that coordinators are trained and have the ongoing resources they need.

At the HRC level, coordinators form partnerships with stakeholders in and outside the school. These partnerships are essential for creating trusting, safe spaces and for linking students to care. HRC coordinators partner with other adults in the school, including the school nurse and school counselors. They work closely with these staff to help ensure that student needs outside the control of HRC coordinators can be met by other professionals, and they serve as a resource for those staff when a student reaches out to them first. Coordinators can also refer to other clinics or agencies for other social service needs. Finally, coordinators play a role in the school community. They show up to sporting or other events, make themselves available to support parents or families, and physically work within the school setting to form authentic relationships.

Key Recommendations for Schools Seeking to Replicate Similar Programs

The following recommendations are drawn specifically from AccessMatters’ HRC program experience but can be useful to implement as-is—or in adapted form—for schools or health systems considering their own version of the HRC model. AccessMatters’ HRC model can be especially promising for schools or health systems seeking a model for school-based health services that does not require a full clinic on site in each school.

Help students improve their health literacy skills.

The HRC program helps young people improve their health literacy skills. Health literacy includes the degree to which people can “find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions.” HRCs help students learn more about their own health needs and goals which can help them identify concerns about their own bodies or well-being and create priorities regarding their own health decisions. One coordinator reported that it is important to simply be present to support students asking questions: Student engagement in their own health care “does not necessarily have to mean that you have to go visit a family planning doctor for a [long-activity reversible contractive] or for treatment or things like that. [A student] can just [say] … ‘I’m thinking about this’ or ‘my friend could be in a situation, and I want to connect my friend with you.’ Or you know, ‘I just have some questions about [x].’”

Another aspect of health literacy is recognizing that health solutions and preferences are often personal. HRC coordinators validate for young people that what is right for their peers may not be right for them. For example, one young person might prioritize the use of a non-hormonal method for birth control while another may appreciate the ability to occasionally skip their regular monthly menstrual cycle by using a pill, path, or ring. Each preference is valid, and coordinators can help young people think about what is right for them.

Emphasize the practice of self-advocacy skills.

While coordinators encourage students to visit and learn more, they also help students be prepared to speak up about their own health needs. HRC coordinators help youth develop self-advocacy skills to go with their improved health literacy skills, and they help them navigate the health care system. Coordinators let students know that they “have a voice” and regularly emphasize to youth that “We’re going to listen to you here, and we’re going to applaud it … We’re going to teach you, guide you, on advocating for your own health.” One coordinator described her ability to help students self-advocate when they come into the clinic as a major strength of the HRC model. For example, in one instance where a coordinator was the MA in the clinic when one of her students came in, she was on the student’s care team during that visit and able to inform the clinician that she and the student had already discussed contraceptive methods in school the week before. She advised the physician to ask the student if they still wanted the same method that they had identified previously or if they had changed their mind. In this way both providers validated the fact that the student already had knowledge but still gave them an opportunity to ask additional questions or change their mind.

Refer students to full-service clinics with warm handoffs.

Although HRCs offer a range of health education and testing services, they are unable to prescribe or administer contraceptive methods (other than distributing condoms) or treat health conditions. Ideally, schools would offer health services on site, but this is not feasible for many schools or districts. Therefore, it is important that health educators and coordinators make warm handoffs to other clinics that are accessible to students. Specifically, a warm handoff is one that does more than refer a student to a clinic. It might include making sure that the student knows where to go; discussing what the appointment will be like and addressing any of their questions or concerns; letting them know who (if possible) they will be seeing; and making sure they know they can always come back to the HRC with questions or concerns or if they need an advocate. Since the students who use the HRC are adolescents who may not have as much experience navigating health care systems and may have transportation challenges, coordinators focus on identifying clinics that are close to each school (even if they are not CHOP clinics) and for which a partnership and mutual commitment to adolescent-friendly services is established. The goal of the referral process is “to get these kids in [and seen]” by another provider for care or treatment and to “keep them safe [and] get them home in a safe manner as well.” Coordinators can also follow up with a young person after an appointment. This can help a young person receive care quickly from a trusted person, access complete care in a full-service clinic, and still have the coordinator serve as an advocate or navigator as they make their next decisions or choices.

Ensure that coordinators receive appropriate training that helps them continue to develop and find useful resources for students.

Each coordinator interviewed spoke about their training in adolescent sexual and reproductive health as a nurse or medical assistant before becoming a coordinator. In addition, the HRC program director at CHOP chooses people for coordinator roles who have an interest in serving adolescents and who can develop rapport with students. Each coordinator receives initial job training along with ongoing opportunities for professional development through AccessMatters and CHOP.

However, each coordinator also spoke about gathering their own resources over years of working with adolescents to which they can frequently refer. One described a binder with information about adolescent development, contraceptives, gender identity, and community resources for various needs (e.g., housing instability, food insecurity, or job training) that she uses daily. These sets of resources pull together information that each coordinator finds useful. Coordinators in other schools should consider creating similar tools to pass on to future coordinators or counselors or to serve as a shared resource document for key providers in the school—school nurses, counselors, etc.

Remember that coordinators are guests in schools who must create trusting relationships with school staff and administrators.

HRC coordinators must work with the principal and other administrators to ensure that services meet the school’s needs. In general, coordinators create relationships with nurses, counselors, coaches, and other teachers in the school so they can become another trusted adult who can refer students to various services. They can also work closely with the school support team that tracks students who may be experiencing challenges and links them to services, especially in community schools.

These relationships help coordinators link students to the types of care they need, such as mental health. One coordinator said, “If you’re having a conversation with this student and you ask about their depression, and they tell you that they’re depressed, or you get into a really deep conversation [about] a trauma history or something like that, it would be so inappropriate to just not have any referrals …” Ideally, a school could provide any needed services on site, but warm referrals and follow-ups outside the school are a strong alternative. For this reason, the external partnerships that HRC coordinators form are important and allow them to confidently refer students to trusted providers.

These relationships sometimes involve challenges. A principal can always ask a coordinator to stop their work or to leave, so investing in positive and trusting relationships is essential to the future of the HRC. The coordinator should know that if they and the principal differ significantly on some issue, the coordinator may be limited in what they can do. For example, one coordinator spoke about a principal’s discomfort with their targeted outreach to special education students. This coordinator was concerned that this could put these students at a disadvantage if they did not understand their sexual health or how to say no to non-consensual sexual interactions. Before the coordinator was able to address the issue with AccessMatters and CHOP, this principal left her position (unrelated to this issue), and the coordinator has worked closely with the next principal who is not concerned about the coordinator supporting special education students. For this reason, it is especially important that the principal and coordinator have a close working relationship in which they establish shared goals and expectations for the HRC and a shared understanding of where and how the coordinator will interact with students. If a coordinator is facing opposition by their school administration, AccessMatters would help strategize ways to address that barrier, including facilitating conversations between AccessMatters staff and the school principal or other administrators.

Gather information and feedback from key stakeholders to meet the needs of students, teachers, principals, and community stakeholders, and to sustain program efforts.

Students are the top priority for HRCs. One coordinator described her primary goal: “Be humble and ensure that you are listening to the people that you need to listen to: the recipients of the services.” However, to serve students effectively, it is sometimes necessary to understand the needs or interests of other stakeholders in the community. For example, principals are held to high standards when it comes to student safety and testing. When coordinators understand how this goal drives principals’ decision making, they can also understand which elements of their work will be easy for a principal to support and which might require more work and problem solving. A potential challenge is to understand which key stakeholders may oppose HRCs and why. Working with stakeholders to understand their needs and sources of opposition can be important to sustaining the work.

These processes require building trust and a sense of community so that principals, teachers, other school staff, parents, health care providers, and other community stakeholders see the coordinator as essential. Building trust requires patience and humility and is worth the investment. Even when challenges arise, this trust can support and boost the work of all stakeholders rather than set them against each other.

Recognize that each school will implement the work slightly differently but that the core values are common.

Schools seeking to create an HRC should think about what space and resources they have and what model might work for them. Key roles of HRC coordinators include creating a safe space for youth to learn about sexual health, forming trusting relationships with young people and the school community, and providing referrals. How each school structures the HRC varies. In one school, the coordinator is stationed in the nurse’s suite multiple days a week. In another school, there is no physical space provided for the coordinator, so they use a “mobile HRC” cart providing only one day of coverage a week at the school. In this school, the coordinator can use the nurse’s exam room for conversations that must be confidential—for example, about STI/pregnancy testing. In other schools outside Philadelphia, providing on site STI testing has not been feasible. In every location, though, coordinators must have conversations early about what is ideal versus what is feasible and continue having these conversations regularly with principals or other administrators. Meeting as many needs as possible while working within the confines of existing resources (e.g., available space or a lab to process STI tests) and norms (e.g., acceptance of STI testing in the school) results in slightly different models in each place.

Each model should also have some amount of predictability and consistency. For example, the coordinator may be present at the school with open hours at the same time each day or week. They should have clear and known processes for conducting STI or pregnancy testing and sharing results. There should be clear and explained processes for parental consent to participate in the program and regarding what information will be shared with whom (i.e., what is confidential). While flexibility is possible in terms of certain school-specific elements, clarity and respect should be prioritized through predictability and consistency.

Footnotes

[1] AccessMatters’ HRC network includes other hospitals, but they are not included in this study.

[2] In 2016, AccessMatters further expanded the program to nine high-need counties throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (see here for more information about the HRC program more broadly). This expansion was funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health. Note that this case study focuses on HRCs that are managed by CHOP in Philadelphia schools (not in expansion counties) and that no interviews were conducted in expansion counties.

The program site described in this case study was selected through a rigorous site selection process that considered factors such as geographic location, populations served, and the success and replicability of the innovation. This case study was informed by five interviews with program leaders and coordinators. Interviewees were given the opportunity to provide feedback on case study content before publication to ensure accuracy. For more information about how the sites included in this process evaluation were selected, read here.

Suggested Citation

Lantos, H. and Shelton, R. (2022). Health resource center coordinators support care through relationship building, health education, and warm referrals. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/8513e8227u

This publication is supported by the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award totaling $2,036,999 with 100 percent funded by OPA/OASH/HHS. The contents reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, OPA/OASH/HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, visit https://opa.hhs.gov/.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram