The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic collapse in the United States led to spikes in unemployment and caused millions of households to depend on unemployment insurance for financial stability. However, not all households were equally likely to apply for and receive unemployment compensation:

Our analysis shows that, among households with children who experienced a loss of employment income early in the pandemic, Latino households and households with low incomes were less likely to receive unemployment insurance than their non-Latino and higher-income counterparts, respectively. In addition, households in states with an alternate base period, which expands unemployment insurance eligibility, were more likely to receive unemployment insurance.

In the economic collapse that followed the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment insurance (UI) supported tens of millions of U.S. workers and their families. Following the initial COVID outbreak in the United States, unemployment rates soared to 15 percent in April 2020, from less than 4 percent in the two prior months. In certain face-to-face occupations and industries, unemployment rates exceeded 10 percent for months before beginning to recover in the last quarter of 2020. Escalated unemployment led to 72 million unemployment claims in 2020, with close to half filed from April to June, and $144 million of total benefits paid out—an increase of more than five times the total amount of UI payments disbursed in 2019. Both regular and emergency UI policies, including extended weeks of eligibility and additional benefits, have played an important role in stabilizing household income, consumption, and the economy during the pandemic.

This brief examines the extent to which households with children who experienced a loss of employment income participated in UI during the pandemic, with a particular focus on low-income and Latino workers, on whom the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a catastrophic toll. Historically, rates of UI receipt among unemployed workers have been low, especially among those with lower levels of education and among Latino workers. Not all workers apply for benefits when they become unemployed, and some may not be eligible. Some low-wage workers fail to meet UI’s monetary eligibility criteria or do not apply for UI because they do not believe that they would be eligible. Given that UI prevents the declines in family and child well-being associated with earnings loss, policymakers need better information to increase participation among families experiencing unemployment.

Specifically, the brief explores how household receipt of UI benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with household characteristics, as well as with state policies that broaden UI eligibility by allowing recent wages to be considered in determining eligibility. We analyze the patterns of receipt among all households with children that experienced a loss of employment income (hereafter, all households) and Latino households (hereafter, Hispanic or Latino households), using recent nationally representative data.

Key Findings Summary

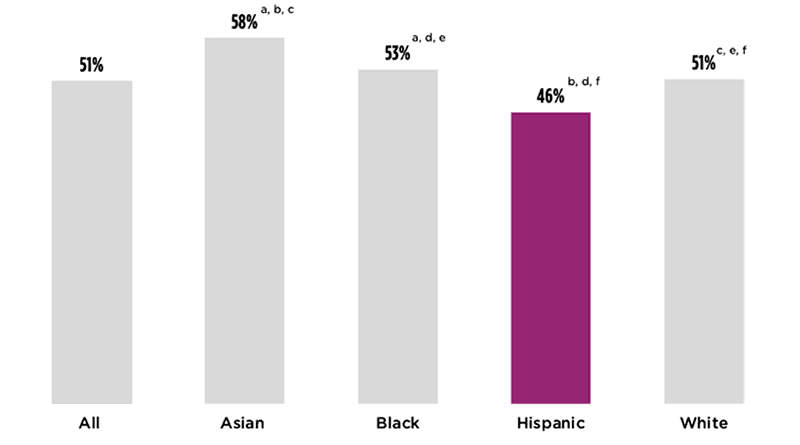

Among households with children who experienced a loss of employment during the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly half (51%) of all households with children had received UI benefits from March 2020 to the end of the 2020 year. The rate of receipt was lower (46%) for Hispanic households with children.

In addition:

- Households with low incomes (less than $50,000) were 6 percentage points less likely to receive UI than those with higher incomes ($50,000–$150,000).

- This negative relationship between receipt and incomes was even stronger for Hispanic households (by 15 percentage points).

- Households headed by someone with a high school degree or below were 4 percentage points less likely to receive UI than households headed by someone with some college education.

- We found an even lower likelihood of UI receipt among Hispanic households headed by someone with a high school degree or below, relative to Hispanic households headed by a member with some college education (by 7 percentage points).

- Households in states that adopted an alternate base period (ABP)—which can expand the eligible pool of UI recipients—were 3 to 4 percentage points more likely to receive UI than those in states that did not have an ABP.

Below, we briefly summarize the policy background, data, methods, and results and conclude with a review and discussion of policy implications.

Context and Research Approach

U.S. unemployment insurance (UI) is a federal-state social insurance program that protects many unemployed individuals from falling into poverty, supports their return to employment, and stabilizes the economy by supporting consumption. States pay out most insurance benefits, with the federal government covering the administrative costs, as well as providing some extended benefits during economic recessions. Under this structure, states design their own UI programs in terms of eligibility, duration of payments, and size of payments within the limits of federal requirements.

Although UI is not typically considered a child and family policy, UI can insure against the risk of income loss for families due to unemployment. In 2019, around 9 out of 10 families with children had a parent employed, and UI benefits reduced the rate of child poverty by 0.2 percentage points after UI benefits were counted. In the 2020 recession, with considerably higher unemployment and UI participation, UI benefits reduced the child poverty rate by close to 2 percentage points. This is equivalent to 1.4 million fewer children living in poverty in 2020 after accounting for UI benefits.

UI may miss or under-cover certain families by virtue of its design—especially those that are headed by low-wage, part-time, contract, or immigrant workers, or by workers with intermittent and informal employment. Because Latino workers have higher representation in these types of employment, UI may reinforce some of the disparities in labor-market incomes. Among major ethnic/racial groups, Hispanic workers are the least likely to receive UI benefits. While UI currently covers almost all salaried employment in the United States, only about one third of all unemployed workers receive UI, with roughly half of unemployed workers ineligible for UI. Researchers have identified both monetary and nonmonetary criteria, as well as administrative barriers, as important factors for low rates of UI receipt among the recently unemployed, particularly for low-wage workers.

To address these gaps in UI receipt, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)—passed at the closing of the Great Recession (2007–2009)—provided financial incentives to states that adopted an ABP to broaden the wage requirement. To qualify for UI, an individual must meet their state’s criteria regarding total wages earned in a past period and causes of unemployment, as well as other requirements. Most states provide weekly benefits that are roughly half of weekly wages earned during the base period prior to filing, up to a maximum amount (typically capped at half of the state average weekly wages), for up to 26 weeks of unemployment. However, states differ in their definitions of base period, benefit level, duration, and other program parameters. A standard base period consists of the four quarters of the last five completed quarters prior to unemployment. Most states that adopted an ABP use wages and employment in the last four completed quarters to determine eligibility for individuals who fail to qualify during the regular base period.

In addition to examining the association between UI receipt and household characteristics, we also investigated whether a state’s adoption of an ABP was associated with UI receipt. We focused on ABP, which was in effect both prior to and during the pandemic, because ABP aims to increase the pool of unemployed who are eligible for UI, particularly those with lower wages or intermittent employment. We acknowledge that the series of emergency provisions enacted during COVID plays an important role in UI uptake rates across the period examined (see COVID UI Policy Facts box); however, because there was little variation in emergency provisions across states, it was empirically challenging to identify the statistical associations between emergency COVID policies and UI receipt. In contrast, there is considerable variation across states in adoption of the ABP: As of January 2020, 36 states and the District of Columbia had implemented an ABP. Moreover, adoption of ABP co-occurred with other modernization provisions from states to address UI access and improve receipt. Thus, we examine ADP as a proxy for states’ likely adoption of a range of strategies and modernization provisions designed to expand UI coverage. These measures might be associated with reduced administrative burdens—including perceptions of ineligibility—among the recently unemployed, which in turn is expected to increase the likelihood of benefits receipt.

COVID UI Policy Facts

At the peak of COVID-related job losses in 2020, the federal government quickly introduced emergency provisions that offered additional benefits on top of state regular payments; extended benefits for recipients who exhausted regular benefits; and extended benefits to workers not typically covered by regular UI programs by additionally covering workers in gig jobs (including independent contractors and workers who don’t have a contract for long-term employment), as well as workers who left employment due to COVID-related sickness, quarantine, and school closures. Driven by the scope of unemployment and by these emergency policies, initial UI claims nationwide increased from an average of 250,000 per week in months before the outbreak to an average of 1.6 million per week in the remainder of 2020.

Findings

For this brief, we examined how the likelihood of household UI receipt is associated with household demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, as well as with a key state policy factor—the ABP. We did this by conducting both descriptive and multivariate analyses for all households with children that experienced a loss of employment income, as well as for Hispanic households.

We found that several household characteristics were associated with the likelihood of UI benefits receipt—most notably, low socioeconomic and education status. Households with incomes less than $50,000 and households headed by someone with a high school degree or less were generally associated with a lower likelihood of UI receipt, and this relationship was more striking among Hispanic households than among all households.

- Fifty-one (51%) percent of all households with children who experienced a loss of employment in 2020 since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (mid-March 2020) also received UI. Less than half, or 46 percent, of Hispanic households reported receipt, a rate lower than among other major racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1).

Hispanic Households Were the Least Likely to Receive Unemployment Insurance (UI) Among All Major Racial and Ethnic Groups

Percentages of households with children and adults that experienced a job loss and reporting that any household member had received UI benefits since March 2020, by race and ethnicity

Click to View Figure Notes and Source

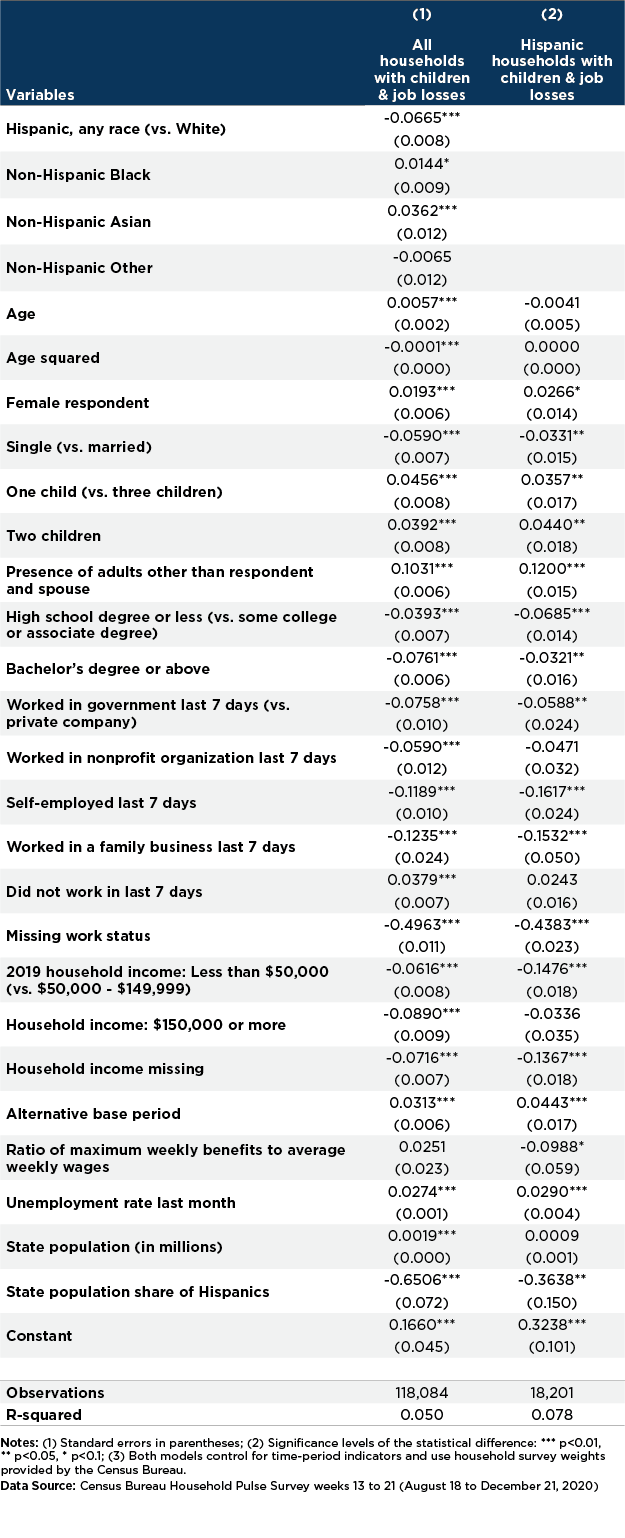

- Our multivariate analysis showed that, overall, households with low incomes (less than $50,000) were less likely to receive UI than those with higher incomes ($50,000–$149,000) by 6 percentage points. This negative relationship between receipt and income was even larger among Hispanic households: Hispanic households with low incomes were less likely to receive UI benefits than higher-income Hispanic households by 15 percentage points (Table 2).

- Households headed by someone with a high school degree or less were less likely to receive UI benefits than their peers with some college education, by 4 percentage points. As with income, the likelihood of receipt was lower for Hispanic households headed by someone with a high school degree or below than for Hispanic households headed by someone with some college by a greater extent: 7 percentage points (Table 2).

- Self-employment and working for a family business were associated with lower likelihoods of UI receipt among all households and among Hispanic households (Table 2).

- The likelihood of UI receipt was higher in states with ABPs than in those without ABPs, by 3 to 4 percentage points—both among all households and among Hispanic households (Table 2).

Discussion

This brief has examined household participation in unemployment insurance (UI), a major U.S. social program that insures workers against the risk of earnings loss, supports consumption, and stabilizes the economy, especially during recessions.

Although UI payments grew by a factor of roughly six (close to 31 million initial payments in 2020) and reduced child poverty by a greater extent in 2020 than in 2019, our analysis found that only half of all households with children that experienced a pandemic-related job loss had received UI benefits by the end of 2020. In addition, the likelihood of receipt was not evenly distributed across households: Latino households and households with low incomes (less than $50,000) were less likely to receive UI benefits than their comparable non-Latino and middle- or higher-income counterparts, respectively. Latino households with lower levels of education or with low incomes were the least likely to receive UI benefits among all racial, income, and education groups examined. In addition, our analysis found some evidence for states’ existing UI systems shaping households’ decisions to take up UI during the pandemic: Adoption of an alternative base period (ABP) was associated with a higher rate of UI receipt.

Although UI payments grew by a factor of roughly six (close to 31 million initial payments in 2020) and reduced child poverty by a greater extent in 2020 than in 2019, our analysis found that only half of all households with children that experienced a pandemic-related job loss had received UI benefits by the end of 2020. In addition, the likelihood of receipt was not evenly distributed across households.

These results generally aligned with the prior literature and add to our understanding of UI participation among Hispanic households. One study found that Hispanic unemployed individuals were both less likely to apply for and to receive UI benefits when applying than their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Hispanic nonapplicants were more likely than their non-Hispanic White peers to report reasons for nonapplication that included not knowing about the benefits, not knowing where or how to apply, and language barriers. However, the most common reason for nonapplication among Hispanic nonapplicants (half of all nonapplicants) was thinking that they were ineligible, primarily because they did not believe they earned enough money or because of another reason not classified in the survey. Similar results have been found for other programs such as TANF. This evidence, alongside our findings, underscores the need to better understand the factors that drive nonparticipation: perceived eligibility, actual eligibility, burden associated with application, and/or monetary criteria that exclude Latino workers due to their job characteristics (for example, low-wage or intermittent employment).

If perceived ineligibility reflects actual ineligibility, this would resonate with our finding about ABPs, since a typical ABP is expected to increase the fraction of those who have lost jobs who are eligible. However, this finding stands in contrast with prior evidence suggesting that ABP was not associated with individual UI receipt from 1987 to 2011, although the researchers noted an effect for low-wage part-time workers, among whom Latino workers are disproportionately represented. This discrepancy may be due to the different periods examined in different studies, and/or data limiting our adjustment of other policies that were in effect. For example, many states with ABPs additionally allowed claimants who previously worked part-time to search for part-time work (instead of full-time), another policy that could increase the number of the unemployed eligible for UI. However, due to high correlation of ABPs, availability for part-time work, and other modernization provisions, we could not isolate the effect of each policy. Program administrators and researchers may leverage detailed administrative data to gauge the extent to which Latino workers qualify for UI under each policy.

This brief has also presented timely analysis of key correlates of household UI receipt, showing significant disparities in UI receipt in several key socioeconomic and demographic groups: households with low incomes, households with self-employed members, Latino households, and Latino households with low incomes and low levels of educational attainment. Based on our findings and those of prior studies, we suggest that future research investigate whether and how UI eligibility criteria limit access to benefits, particularly among workers with lower levels of education and in low-wage jobs. We also suggest that policymakers consider UI policies that research suggests can improve receipt, likely through increased eligibility or reduced administrative barriers.

Lisa. A. Gennetian is the Pritzker Associate Professor of Early Learning Policy Studies at Duke Sanford Center for Child and Family Policy. Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

The authors would like to thank Alix Gould-Werth for her insightful feedback on an earlier draft of this brief.

Data and Methods

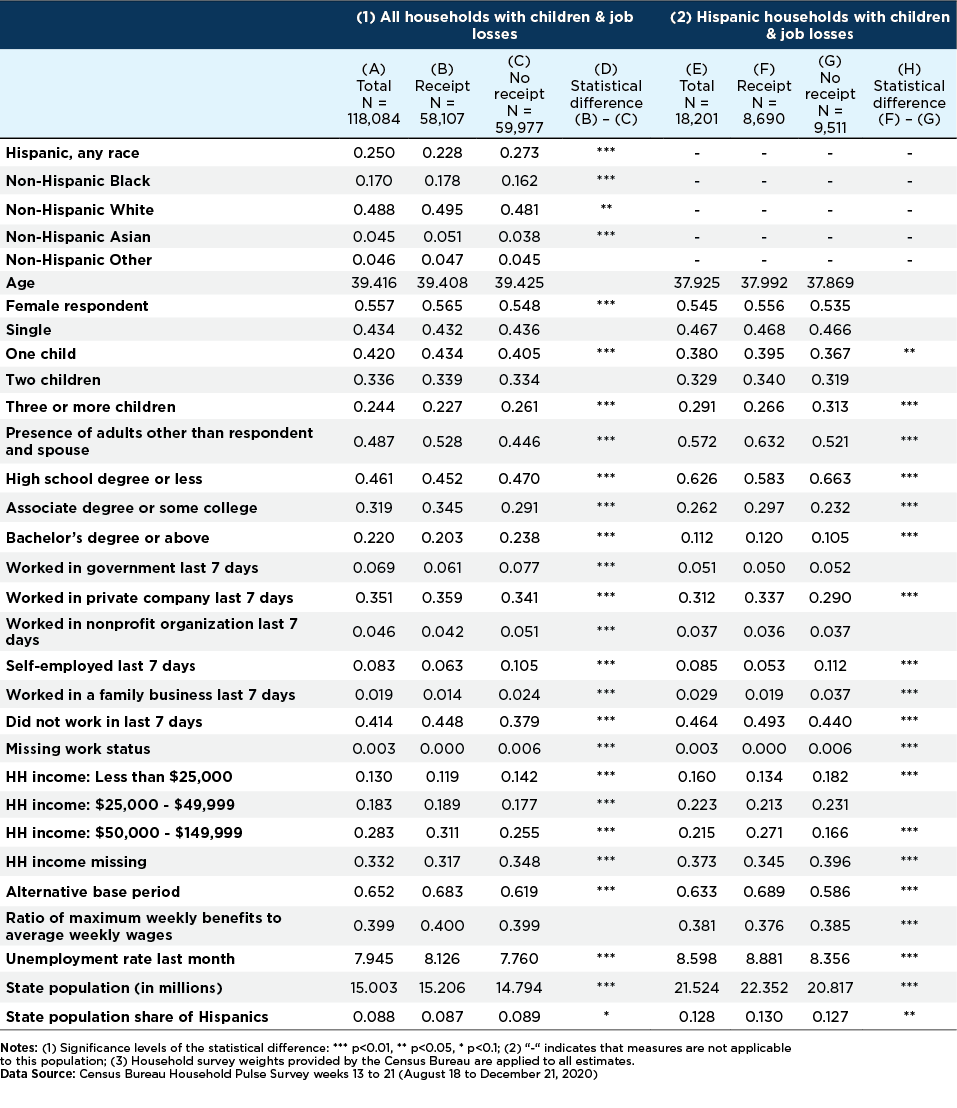

We analyzed household-level data from the Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a federal experimental effort to collect timely and nationally representative data of households in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. For HPS, multiple cross-sectional samples are drawn biweekly to inform trends in key measures of household well-being throughout the pandemic. We focused on data from the 13th to the 21st biweekly periods (August 19 to December 21, 2020) because the reference period of unemployment matches with that of UI receipt during this time. To select our analytic samples, we began with 279,756 households with children, including 33,656 Hispanic households with children. We eliminated 49 percent of households and 38 percent of Hispanic households without a loss of employment income (referred to as a job loss); and another 3 percent of households and 3 percent of Hispanic households, including those with respondents ages 65 and older and those in the District of Columbia for which data on average weekly wages were not available. This led to a final sample of 118,084 households with children and a job loss (of which 18,201 were Hispanic households) in 50 states.

We conducted multivariate analysis by estimating linear probability models to adjust for confounding factors and focused our investigation on the relationship between each characteristic of the household or state UI policy and UI receipt. Our key outcome of interest was whether the household had received UI benefits since March 13, 2020. Specifically, the Household Pulse Survey, which was available in both English and Spanish, asked respondents (one per household), since March 13, 2020, (1) whether they or anyone in their household had experienced a loss of employment income; (2) whether they had received UI benefits; and (3) how many people in their household had received UI benefits. In contrast, respondents were asked about their own employment status only in the last seven days, rather than since March. We focused on household receipt—that is, receipt by anyone, including the respondent—rather than on respondent receipt, partly due to this data limitation and partly because we aimed to focus on household well-being (and thus considered employment a household-level decision).

Our analysis considered key demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the household, including age, gender, race and ethnicity, and marital status of the respondent; number of children under age 18; presence of adults other than the respondent and their spouse in the household; the respondent’s educational attainment; their sector of employment in the last seven days (exclusive categories: government, private company, nonprofit organization, self-employment, family business, did not work); and their household income from 2019. With respect to state policies, we examined how UI receipt was linked to the state’s adoption of an ABP and adjusted for state differences in benefit level, measured by the ratio of maximum weekly benefits as of January 2020 to the state’s average weekly wages in March 2020 (namely, maximum benefits adjusted for average wages). To construct our measure for the benefit level, we retrieved data on state UI laws in an annual report published by the U.S. Department of Labor and from estimates for state average weekly wages from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

It is worth noting several limitations. First, the Household Pulse Survey is designed to collect immediate data about household well-being during the pandemic and does not have detailed data on unemployment and prior employment histories that allow us to identify actual UI eligibility. We cannot establish evidence for whether the gaps in receipt are due to differences in UI eligibility or differences in participation among those eligible. Second, some of the factors we examined, including Latino ethnicity, may be correlated with unobserved job characteristics that result in differential rates of receipt, so the relationship between a factor and the likelihood of receipt may be mixed with influences from job characteristics. For example, if we had had information on whether households included members that worked in seasonal jobs and adjusted for this data, we might have found seasonal jobs to be the main contributor of low receipt, rather than Latino ethnicity. Despite these empirical challenges, our evidence largely points to the fact that smaller proportions of households with low incomes—and of Latino households with low incomes and low levels of education—received UI during the pandemic.

Appendix 1. Average Characteristics of Households with Children and Job Losses, Total and by Unemployment Insurance Receipt Since March 2020

Appendix 2. Linear Probability Models for Household Receipt of Unemployment Insurance Benefits

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram