Current Policy Landscape Prevents Subsistence Protections and Practices Necessary for Alaska Native Children and Families’ Well-being

Subsistence is a critical protective factor for Alaska Native children, family, and community well-being (including Indigenous cultural continuity); a vital aspect of environmental justice; and a key contributor to the sustainability of Alaska (including Indigenous cultural continuity)—demonstrated through findings drawn from the author’s review of extant literature and from her on-site research with members of an Indigenous community in Alaska.

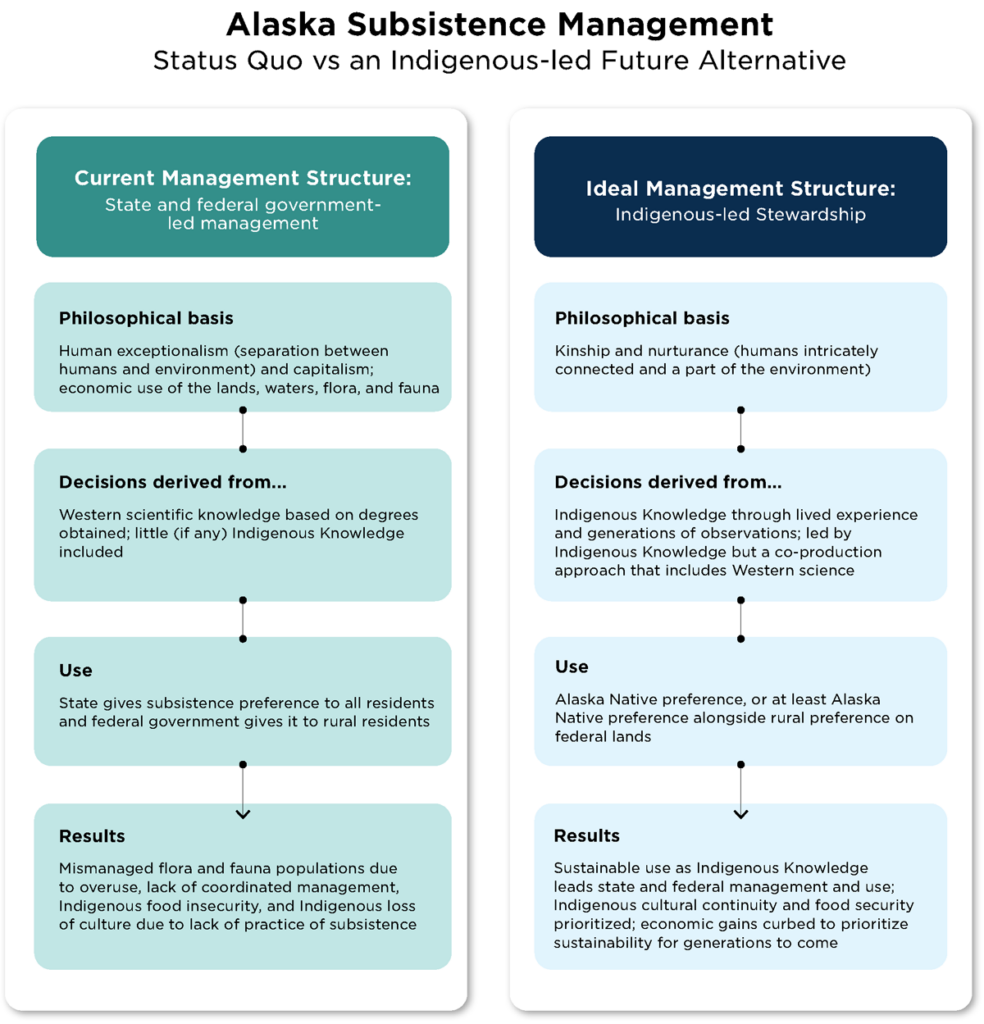

While acknowledging that Alaska Natives would be best served by assuming full stewardship of the land, waters, and subsistence rights in Alaska, the author offers a set of recommendations for the state of Alaska and the U.S. federal government—drawing on examples of successful co-management practices—to improve Indigenous communities’ well-being through the more incremental transfer of decision-making powers over Alaska’s lands and waters.

This brief shares findings from the author’s qualitative futures study conducted in partnership with the Ninilchik Village Tribe (NVT) and presented, in part, in an article titled “Alaska Native Subsistence Rights: Taking an Anti-Racist Decolonizing Approach to Land Management and Ownership for Our Children and Generations to Come.” The brief will show how subsistence is a critical part of Alaska Native cultures and that the ability to pass subsistence practices to children is an important protective factor for their well-being.

The brief first introduces (“situates”) the author as an Alaska Native researcher. Second, it presents the context necessary to understand the complex legal and cultural issues it raises. Third, it describes the community of Ninilchik, which partnered with the author in the research, as well as the methodology used for this research. The fourth section reviews the history of Alaska’s colonization to show how colonization has separated Indigenous Peoples from subsistence practices and to situate the research findings for Ninilchik; it also reviews both federal and Alaskan state legislation governing subsistence and land management. The fifth section offers findings from the case study regarding Ninilchik community members’ perspectives on subsistence. In the sixth section, the author offers recommendations for federal and Alaska state government policymakers to remove the barriers that lead to unsustainable management of lands and waters and to food insecurity, and that prevent Alaska Natives from practicing subsistence. The conclusion reaffirms the importance of subsistence as a protective cultural factor for Alaska Native Peoples and children.

Indigenous Knowledge

Knowledge which is held by different Indigenous Peoples is the wisdom, insights, and ways of knowing they have acquired through their close interactions with the natural environment, their cultural traditions, and their social systems. It is living, place-based, temporal, and spatial; is based on evidence-based observations, experiences, and practical wisdom; promotes sustainability; is. drawn from social, cultural, spiritual, and ecological engagement; is adaptable and dynamic; considers the environent to be kin; and has been passed down generationally, in both oral and written form.

I. Situating the Researcher

As an Indigenous person and researcher, it is important to me to situate who I am in my work. This helps those I partner with (and my readers) understand where my perspective comes from. Additionally, I situate myself in research to address power relationships and demonstrate my respect to those with whom I partner. This is part of the process of reflecting on who I am in relation to the research project. To do this, as an Indigenous person, I draw on the Indigenous concept of relationality among all people and things. In doing so, I understand my role as an Indigenous relative and a caretaker to the natural world, understanding also that the plants, animals, waters, and sun all provide for my survival. Finally, I situate myself so the reader can understand my role in translating the Indigenous Knowledge shared with me in the case study to terminology that can directly inform policymakers.

My name is Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon. My Iñupiaq name is Sauyaq, which means drum. I am Iñupiaq and an enrolled member of the Nome Eskimo Community, a federally recognized Tribe in the United States. I was raised near Homer, Alaska on my paternal grandmother’s (Mary Jean Kaguna Yenney’s) reindeer ranch, and I grew up learning Iñupiat Ilitqusiat (Iñupiaq values) from her. While growing up, I learned how the Iñupiaq side of my family experienced, and continues to experience, colonization and racism. This directly affected my family and resulted in culture and language loss. I provide this explanation so the reader understands that I approach research with an Indigenous mind—recognizing that, as an Indigenous researcher, I cannot be silent. Instead, I must beat the drum and lift the voices and Knowledge of Indigenous Peoples. In my research and evaluation work, I partner with Indigenous Peoples to address colonization and historical trauma by viewing Indigenous culture as a protective factor for healing, promoting resilience, and advancing child and family well-being.

II. Context

Indigenous Peoples living in Alaska are grouped together under the term Alaska Natives but comprise 231 distinct federally recognized Tribes (229 Tribal governments) and speak over 20 different languages. Alaska Natives make up 19.6 percent of the population in Alaska, with 46,551 children under age 18. Alaska Natives and their lands were first colonized by Russia in 1741 and then by the United States in 1867, with the purchase of Alaska from Russia (rather than from the Indigenous Peoples who were the actual rightsholders). Initial colonization included war, slavery, forced boarding schools, land theft, diseases, and racism—only some of the atrocities that led to lasting historical, cultural, and intergenerational trauma, and to the loss of Indigenous languages and cultures. Colonization continues today but is practiced in new ways, including the use of Indigenous lands for resource extraction and without consent or consultation, the commercial appropriation of Indigenous cultures, and ongoing discrimination and racism. Combined, these ongoing threats diminish Indigenous rights to practice subsistence (see box below), which are vital for children and families’ well-being.

Cultural Continuity

The act of Indigenous people passing on their historic/present culture, identity, language, activities, beliefs, and resources to future generations.

Colonization

The process by which external powers established control and dominance over the lands, resources, and societies of Indigenous Peoples. This often involved the imposition of political, economic, social, and cultural systems that subjugated and marginalized Indigenous populations, leading to significant impacts on their lives, cultures, and rights. It often included territorial dispossession and settler colonialism, political subjugation, economic exploitation, social disruption and violence, slavery and genocide, and cultural assimilation.

Prior to 1741, Alaska Natives cared for and nurtured the lands and waters for over 10,000 years through a relationship-based perspective, caring for the earth that, in turn, provided people what they needed to survive. Now, the majority of Alaska’s land and waters—besides the one reservation of Metlakatla and a small amount of trust land—are managed by the U.S. federal and Alaska state governments, which privilege economic ventures and resource extraction over sustainable management, resulting in harm to the lands and waters that Indigenous Peoples rely on for food security. Control over the majority of Alaska’s land is by the state and federal governments instead of Alaska Native Tribal Nations. This means that Alaska Natives’ food sovereignty, via their rights to engage in subsistence, are limited and determined by state and federal governments and not by the Tribal Nations. The sovereignty and self-determination of all Indigenous Nations must be respected so they can steward their traditional lands and waters, practice subsistence, and address the reasons they oppose harmful environmental practices.

In order to address the issues of Indigenous land and water stewardship and subsistence rights, policymakers must consider the lack of these rights to be an environmental injustice. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” The EPA further defines “meaningful involvement” as a condition under which “People have an opportunity to participate in decisions about activities that may affect their environment and/or health … can influence the regulatory agency’s decision; Community concerns will be considered in the decision-making process; and Decision makers will seek out and facilitate the involvement of those potentially affected.” Indigenous Peoples have experienced environmental injustices since first contact, and Alaska Native Tribal Nations continue to be largely uninvited to federal and state land and water policy discussions (as will be described below), diminishing the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in stewardship decisions.

Subsistence

Indigenous understandings of subsistence go far beyond hunting, fishing, and gathering food. Indigenous Peoples see subsistence as a way of life, a connection to their ancestors, part of their spirituality and ceremonies, an aspect of their relationality to the world and their role as protectors and caregivers to the earth, and a contributor to their overall well-being.

Food Sovereignty

The right of Indigenous Peoples to “define their own hunting, gathering, fishing, land, and water policies; the right to define what is sustainably, socially, economically, and culturally appropriate for the distribution of food and to maintain ecological health; and the right to obtain and maintain practices that ensure access to tools needed to obtain, process, store, and consume traditional foods.”

In addition to being an environmental justice issue for Indigenous Peoples, connection to the environment is tied to well-being through cultural practices, arts and crafts, medicinal plants, social relationships with humans and the environment, and traditional subsistence foods and practices. Indigenous Peoples across the world have a relational view of the environment, seeing the plants, animals, waters, lands, sky, sun, and all else as relatives; one author refers to this as “kincentric ecology.” This connectedness to the earth is a significant part of Indigenous identity. From this perspective, Indigenous Peoples do not “manage” the lands or waters but instead steward, nurture, and care for them in ways that reflect humans’ obligations to their other kin, in which fellow humans are seen as part of a larger system and not independent of other things. Indigenous stewardship practices are intricately tied to the future, creating sustainable use now so resources are still there for future generations. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Indigenous author/researcher Robin Wall Kimmerer, PhD (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) explains that, to settlers, “land was property, real estate, capital, or natural resources … [Indigenous people, by contrast, see land as] everything: identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library” that sustains them (p. 17). Indigenous Peoples understand land as a gift and treat the earth with kindness and reciprocity, care, and nurturance—a two-way relationship based around symbiosis, where people take only what they need so that other populations can sustain themselves. This Indigenous worldview stands in contrast to the nation’s capitalist economic system, which—because it prioritizes profit generation—treats the earth’s natural resources (its trees, land, waters, animals) as commodities to be used to produce capital, often at the cost of pollution, sickness, and species and biodiversity loss.

What subsistence means to Alaska’s Indigenous families and their children

In a very narrow sense—including, for example, how it is defined in legislation—subsistence means the acts of hunting, fishing, and gathering food. This narrow perspective, however, sees humans as separate from their environment (a concept known as human exceptionalism, where humans and human society are independent from the ecosystems in which they are embedded) and undermines the role of subsistence as a cultural and spiritual practice that is so much more than harvesting food. Indigenous subsistence brings a sense of well-being and a connection to ancestors, represents the sacred way in which Indigenous Peoples live in relationship with the natural world, and is an integral part of Indigenous identity shared through multi-generational engagement as children and youth learn from their parents, aunties, uncles, and Elders. Subsistence is commonly practiced through harvesting, processing, and sharing food; singing, dancing, and telling stories about subsistence practices; and eating together. Most Indigenous languages do not have a word for subsistence and generally see subsistence as a way of life that encompasses all parts of life. The Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska held multiple listening sessions on food security as part of an exercise to assess the Arctic and its resources from an Inuit perspective; speaking in a session, one community member explained that subsistence “encompasses everything. Everything we do from the time we wake up, to [the time we] sleep, from when we are born, to when we die.”

Subsistence is vitally important to Indigenous communities in Alaska for two major reasons, both of which are complex and multi-layered. First, subsistence provides the means of sustaining most Indigenous communities in Alaska, which are rural and only accessible by boat or plane; there is no road system across much of the tundra. Due to this, the cost of groceries is prohibitively high. Indigenous subsistence is a part of these communities’ economic well-being and, currently, “the lack of decision-making power and management authority … [by Alaska Natives is] … the greatest threat” to Indigenous children and families’ food security. Second, and arguably more importantly, subsistence is critical to Alaska Natives’ ability to maintain their cultural and spiritual practices and stewardship of the earth, which are passed on to children and youth as a protective aspect of their identity.

Millennia of Indigenous Knowledge passed down orally demonstrates that culture serves as both a protective and preventive factor against the ills of colonization and the resulting historical trauma that manifests through health disparities in mental health (high suicide rates), behavioral health (high substance misuse rates), physical health (high rates of diabetes), and social/relational health (exposure to high numbers of Adverse Childhood Experiences). Subsistence is one way by which humans are interconnected with their environment and ecology. As Indigenous people practice subsistence, it promotes their health and well-being by strengthening relationships with place, the land and water, plants, and fish and animal populations.

When Indigenous people pass on their subsistence culture to future generations, this continuity protects children, youth, and families via their engagement in six key cultural experiences: 1) being enculturated through learning about their Indigenous identity and cultural practices; 2) engaging in traditional activities promoting physical activity and the eating of nutritious foods; 3) having relationships with the land; 4) being connected to family and the community by building memories and familial bonds, which enable intergenerational teachings; 5) learning Native languages (words for plants and animals); and 6) learning about spirituality and relationality with the surrounding ecology. Engaging in subsistence activities connects Alaska Natives to one another and to their ecology, promoting well-being. It also brings people joy as they practice subsistence with family.

Despite the known benefits of subsistence contained in Indigenous Knowledge and shared orally, there is a lack of research in the United States on subsistence and how it supports well-being, specifically with youth populations. One study with Dena’ina Athabascan youth found that “subsistence and other cultural activities, in principal and in practice, are protective factors that promote youth wellbeing by fostering connectivity, continuity and coherence to valued others—past, present and future.” This brief will discuss the author’s own research on subsistence, broadening the previous limited work.

III. Research Site and Methodology

This brief is based on findings from the author’s study conducted in partnership with the Ninilchik Village Tribe (NVT) in Ninilchik, Alaska. NVT is a federally recognized Tribe and the only form of government in Ninilchik (there is no city municipal government). The NVT has over 900 members worldwide, with approximately 15 percent living in Ninilchik.1 The Tribe is composed of people from multiple cultures due to Russian intermarriage policies (used as a method of colonization) during the fur trade era and because Ninilchik’s waterway location facilitated intercultural connections through travel. When this project was conducted in 2018, Ninilchik’s population was 749 people. Additionally, Ninilchik is classified as a rural community according to the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which allows residents to have federal subsistence priority (explained in detail below).

The author partnered with NVT and designed the study over a 12-month period, along with a liaison NVT asked her to work with (they communicated with the Tribal Council). Heather, the liaison, and the NVT Tribal council settled on the method of ethnographic futures research (EFR), which was used through an Indigenous relational framework so that it was allied with Indigenous methodologies. The project methodology was based on Indigenous principles, which 1) are asset–based; 2) are participatory; 3) privilege Indigenous Knowledge and include the co-production of knowledge; 4) engage in free, prior, and informed consent; and 5) create space for storytelling and trust building through EFR. EFR is a scenario-based methodology that covered three possible futures with each of the 30 participants—optimistic, pessimistic, and most likely futures. In these future scenarios, participants are situated in 2038 as their present—20 years from the time of the project interviews—and then “backcast,” or asked to look back over the last 20 years to see how they got to where they are in the “now” scenario of 2038. This method works well with Indigenous cultures, as many are not comfortable making projections about the future, which is seen as a shaman’s or medicine man’s/woman’s role. After discussing the scenarios, participants identify what role they play in helping their community achieve the optimistic future they outlined (see Gordon, 2021 for a full explanation of the project methods). Studying how participants described these futures helps identify what the community needs and wants, what they want to avoid, and what steps they should take to reach the optimistic future for their community.

IV. A History of Colonization and Legislation Governing Land and Water Management in Alaska

Colonization and land claims

Colonization of Alaska began with Russian occupation in 1741 and continued after the purchase of Alaska by the United States in 1867. Colonization by both countries included land exploitation, the harvesting of animals to extinction, the enslavement of Indigenous populations in the Aleutian Islands, war with the Tlingit, and bringing devastating diseases that killed up to 90 percent of the Indigenous people in some communities. The permanent community of Ninilchik was established by the Russian-American Fur Company in the early 1800s in an area in which the Indigenous Denaʼina people had lived for centuries. Russian fur traders who married Alaska Native women throughout the state settled in Ninilchik as a retirement community. Initial colonization was followed by Russian Orthodox and then Western Christian missionaries, U.S. government and missionary boarding schools, and racism—the combined effects of which are tied to lasting historical, cultural, and intergenerational trauma, as well as extensive loss of Indigenous language, culture, and land. This trauma is further tied to adverse current community, family, and individual conditions.

Present-day colonization in Alaska is practiced in new ways, including via environmental injustices where Indigenous Peoples are not able to make decisions about resource extraction on their traditional lands. For example, Alaska Natives are not the primary decision makers regarding oil drilling issues in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and at the Willow Project; although supported by Alaska Native corporations involved in resource extraction, these extractive activities are strongly opposed by local communities like the City of Nuiqsut, the Native Village of Nuiqsit, and the Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic (SILA), all of which rely on subsistence for survival.

The remainder of this section focuses on how modern colonization creates systemic and institutional barriers that keep Indigenous Knowledge from being included in land and water management and prevent Alaska Natives from passing their protective subsistence cultural practices to their children and youth.

Federal subsistence legislation and management

This section reviews four main developments in federal legislation regulating Alaska Natives’ land management. For a brief overview of the most relevant federal legislation impacting subsistence rights, see “Relevant Federal Acts” box.

Relevant Federal Acts

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971 was the land claims settlement for Alaska that resulted in Alaska Native Tribes losing land and subsistence rights.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) of 1972 further prohibits subsistence, restricting the taking and use of marine mammals unless the person is ¼ blood quantum Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut (blood quantum set in ANCSA) residing in Alaska, on the North Pacific Ocean, or the Arctic Ocean.

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980 restored subsistence rights removed by ANCSA, but granted these rights to all rural Alaskan residents instead of specifically to Alaska Native people.

Colonization of Indigenous Peoples continues through the use of blood quantum to restrict subsistence and land rights, including in the legislation that established land claims in Alaska.

Blood quantum is a system originated by the U.S. federal government in treaties in the 1800s to dispossess Indigenous people from their lands and force them to assimilate. Blood quantum further racialized Indigenous Peoples based on their skin color and attempted to categorize them by their mixed heritage and lineage by their amount of “Indian” blood as “half-breeds,” “half-bloods,” or “quarter-bloods.” This practice continues today, as American Indian and Alaska Native people in the United States are issued a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) card from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) stating their blood quantum. Blood quantum is also written into legislation. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971 was the land claims agreement in Alaska. ANCSA removed all land from Alaska Native Tribal Nations except for the Metlakatla reservation; it also removed all Alaska Native subsistence rights.

Only 10 percent of the original land to which Alaska Natives laid claim are still held and owned, but by Alaska Native regional and village for-profit corporations instead of Tribes (this is not reservation land as in the continental United States, where Tribes have some environmental rights over the land). Alaska Natives with one quarter or more blood quantum were eligible to enroll in these corporations. Because Alaska Native communities have high rates of poverty and unemployment, some Alaska Native regional corporations have engaged in resource extraction on their lands, which—although contrary to a relational caring perspective for the environment—is done out of economic necessity due to economic vulnerability, poverty, and a lack of other options to provide for their people.

Because ANCSA removed subsistence rights that Alaska Natives require to survive, Alaska Natives lobbied for those rights to be returned; in 1980, Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA).

Although Alaska Natives lobbied for a Native subsistence priority, ANILCA instead granted priority to all “rural” Alaskans after the state objected to a Native preference. (Special subsistence rules exist for Alaska Natives and marine mammals, as outlined in the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972). ANILCA defines subsistence as “the customary and traditional uses by rural Alaska residents of wild, renewable resources for such direct personal or family consumption as food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools or transportation; the making and selling of handicraft articles…” This definition leaves out Indigenous perspectives—such as a kincentric and relational view of the world and environment, reciprocity, stewardship, spirituality, and connection to ancestors—resulting in an economic view of subsistence instead of a holistic view that involves not only harvesting but also caring for the environment.

Further, according to ANILCA, urban residents can practice subsistence on federal lands unless there is a species shortage in the area and the rural preference goes into effect. If there is a species shortage, Alaska Natives who have moved to urban areas and seek to practice their subsistence culture on their rural homelands are not legally permitted to do so. This severs their connections to their communities, Tribal Nations, sense of communal cooperation, Elders and youth, culture, spirituality, and the earth—all of which are intricately tied to their well-being. Additionally, the land held by Alaska Native regional and village corporations have no federal subsistence priority and are not included in ANILCA.

In an attempt to get Alaska to comply with the rural subsistence priority in ANILCA, the federal government offered the state of Alaska the opportunity to not only manage the state lands it already managed (allowing subsistence by all state residents), but also the federal lands covered under ANILCA (allowing subsistence only to federally determined rural communities). Anti-subsistence groups lobbied against this and won in the courts when the Alaska Supreme Court (1989) found ANILCA to be unconstitutional under the State Constitution. The state constitution gave subsistence priority to all residents, while ANILCA restricted priority to only rural residents. To this day, Alaska does not have a rural subsistence priority on state land.

After this ruling, the federal government took over management of federal lands in Alaska in 1992 through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS); since then, USFWS management has expanded to also include fisheries and waters, splitting management of many land and water resources between the state and federal governments. Sixty percent of Alaska is federally owned land regulated by the federal government (rural subsistence priority), while the state regulates the 30 percent (subsistence priority for all state residents) that it owns. The remaining 10 percent is privately owned and includes the 40 million acres owned by the Alaska Native corporations (not part of the federal rural subsistence priority). With state and federal management of 90 percent of state lands, Alaska Natives organized a variety of subsistence organizations—governing seals, whales, walruses, birds, polar bears, and other animals—to be able to participate in management discussions that affect their survival. Nevertheless, these arrangements—a combination of co-management and cooperative agreements—are only with the federal government on federal lands and waters and are fraught with problems: 1) The arrangements feature power imbalances between the federal government and Alaska Native organizations; 2) they do not acknowledge Tribal sovereignty or co-manage land with the Tribes; 3) they pit Indigenous cultural and food security interests against economic and exploitative land use; and 4) they do not meaningfully include Indigenous Knowledge.

The Federal Subsistence Board (Board) is supposed to consider its subsistence users’ perspectives on federal land management, as well as propositions made by Regional Advisory Councils, but often fails to do so equitably in practice.

Until 2012, no rural subsistence users (including Alaska Natives) were on the Board and there was no Tribal consultation around subsistence decisions. Now, two rural subsistence users sit on the Board, which also holds Tribal consultations. However, systemic barriers exist: The two rural users and the chair (often Alaska Natives) are consistently outvoted and Indigenous Knowledge is not included in decision making. The Board’s other voting members include five federal agency directors of the USFWS, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Forest Service. The Board determines which communities are rural and, by extension, which have permissible rural subsistence use; regulates species not already co-managed; and regulates federal lands, waters, and fisheries. The Board’s definition of rural leaves out communities with Alaska Native residents who are heavily dependent on subsistence for their food security and culture, such as Juneau and Ketchikan (which is currently applying for rural preference).

Additionally, if the Board rules that rural preference is in effect in any area in Alaska (due to low species counts), Alaska Natives living in urban cities (like Anchorage) are not legally able to practice subsistence in that area—even if it represents their traditional home area where they have practiced subsistence as a family unit for centuries and on which they rely on for their well-being.

In addition to the Board, ANILCA created 10 Regional Advisory Councils (RACs)—comprised of regional commercial, subsistence, and sports users—to make recommendations and proposals to the Board.

Although the RACs are 70 percent comprised of people representing subsistence interests and 30 percent representing commercial and sport interests—and despite the Board’s mandate to defer to RAC recommendations—Alaska Natives participating in RACs are still not finding their perspectives included when the Board makes its final decisions (e.g., on fisheries and marine mammals). For example, NTC’s president, is on the Southcentral RAC but Tribal members still feel that their Indigenous Knowledge is not listened to; see the Findings section for more information. Additionally, the USFWS also employs an Alaska Native Affairs Specialist to implement government-to-government consultation with the Tribes, but this position also does not respect and understand Indigenous Knowledge as a valid and scientific approach to management; as a result, the USFWS largely does not draw on Indigenous Knowledge in its management practices.

Ninilchik Village Tribal Elders Outreach Coordinator, Tiffany Stonecipher, teaching the next generation how to tie knots that are vital to subsistence activities.

State subsistence legislation and management

This section reviews Alaska’s state policies and practices on subsistence, detailing those related to Indigenous residents. These policies and practices may differ from their federal counterparts.

While ANILCA prioritizes rural subsistence users on federal land, the state of Alaska defines all state residents as subsistence users.

This definition means that the state’s urban population can practice subsistence on state lands, which depletes resources. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) manages state lands, waters, and fisheries. Although ADF&G employs subsistence resource specialists to work with Alaska Native Tribal Nations, Ninilchik Tribal members emphasized to the author that the economic needs of sports and commercial fishing lobbies tend to drive state management decisions at the expense of subsistence users. ADF&G has advisory committees throughout the state to obtain local perspectives on management. Decisions are made by the Boards of Fisheries and Game, which pass regulations on use, conservation, and development of resources.

Board members are appointed by the governor and, because these boards are made up of political appointees, their members and decisions tend to align with state policy on revenue production and resource extraction instead of Tribal perspectives on subsistence and land nurturance for sustainability. These boards are majority non-Indigenous and create systemic barriers against the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in decision making.

Because the state privileges commercial use of Alaska’s waters and lands, Indigenous Tribes and people have sued Alaska multiple times over subsistence rights (as well as resource extraction, detailed in the Colonization and land claims section above).

In 1984, Katie John requested that the Alaska State Board of Fisheries open Batzulnetas for subsistence fishing. She was denied, even though sport and commercial users were taking hundreds of thousands of salmon downstream. This led to a 1985 lawsuit, in which the Native American Rights Fund sought to compel the state to re-open the fishery. This lawsuit continued to 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied the State’s petition to be heard. As a result, subsistence activities are now allowed in Batzulnetas and federal subsistence fisheries protections have been extended to all federally navigable waters.

In 1988, the Kenaitze Indian Tribe also sued the state over subsistence fishing. District of Alaska Judge Kozinski’s opinion states, in part, that “[t]his is a case involving a clash of lifestyles and a dispute over who gets to fish. … The state has attempted to take away what Congress has given [ANILCA 1980], adopting a creative redefinition of the word rural, a redefinition whose transparent purpose is to protect commercial and sport fishing interests.” (In Ninilchik, the NVT has also had to sue for its subsistence rights, which is explained further below.)

In 2020, Alaska took a firmer stance against Alaska Native subsistence users by suing the Board for its special action during the COVID-19 pandemic that allowed Alaska Native rural subsistence communities facing food insecurity to hunt out of season. Tribes in Alaska saw this act by the state as structural racism and a direct attack on the rights of sovereign Tribes to feed their communities; ultimately, a federal judge ruled against the state, saying that the Board had the right to regulate hunting on federal land in Alaska. Lawsuits for subsistence fishing rights are ongoing and Earth Justice (a nonprofit environmental law organization) filed a lawsuit on April 7, 2023 on behalf of the Association of Village Council Presidents and Tanana Chiefs Conference (who collectively represent over 100 Tribes in Alaska). The suit was filed in U.S. District Court against the National Marine Fisheries Service over the limits allowed for groundfish catch in the Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands, claiming that subsistence fishing has been halted to give preference to commercial fishing.

Recent federal efforts promoting Indigenous Knowledge

As of 2021, the unprecedented appointments of Indigenous people—including the appointment of Deb Haaland (New Mexico Laguna Pueblo) as Secretary of the Interior—have led to increased federal government engagement with Indigenous Knowledge and co-management with Tribes. Secretary Haaland is the first Indigenous Secretary and has worked to allow Indigenous Nations to manage their own lands and to reallow Alaska Tribes to put land into Trust. Secretary Haaland also increased Tribal stewardship of federal lands, resulting in numerous co-management agreements and even full management by Tribes. Charles F. Sams, III (Cayuse, Walla Walla), another 2021 appointment, became the first Indigenous Director of the National Park Service. A third key Indigenous appointment was Raychelle Aluaq Daniel (Yup’ik Alaska Native) as the Arctic Executive Steering Committee (AESC) deputy director in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Daniel’s appointment resulted in memos on Indigenous Knowledge in federal decision making, federal guidance on Indigenous Knowledge, implementation of guidance, an explanation on Indigenous Knowledge, and various listening sessions. The White House also put out a fact sheet on actions to support Indigenous communities.

Some states and Tribal Nations are also creating new co-management agreements and land and water and animal restoration projects. In Alaska, there are longstanding federal co-management and cooperative agreements (governing, for example, marine mammals, birds, and polar bears); however, these agreements are with Indigenous organizations, not Tribal Nations. Additionally, federal officials have made some policy decisions supporting Indigenous interests in Alaska, but these have been limited to roadless protections in the Tongass National Forest, stopping the Pebble Mine to protect salmon fisheries in Bristol Bay, and protecting the U.S. Arctic Ocean from oil and gas leasing. None of these decisions address the longstanding problems of co-management in Alaska, which include a failure to acknowledge Tribal sovereignty, value Indigenous Knowledge, or prioritize Indigenous cultural needs and food security against exploitive land use.

Most recently, in April 2023, the White House passed an executive order (EO) on Environmental Justice to create a White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council and require all federal agencies to create Environmental Justice Strategic Plans. This council is tasked with ensuring that all people in the United States have a healthy environment with healthy foods and clean water. The EO states that people will be able to “meaningfully participate in agency decision-making processes” and that the federal government will remove barriers to meaningful involvement. The EO specifically addresses respect for Tribal sovereignty and self-governance through Tribal consultation and improved collaboration with Tribal Nations on federal policies (pertaining only to federally recognized Tribes federal government “must recognize, honor, and respect the different cultural practices—including subsistence practices, ways of living, Indigenous Knowledge, and traditions—in communities across America.” The EO’s callout of subsistence as an aspect of environmental justice is vital to respecting Indigenous leadership on federal lands and waters.

Summary of systemic and institutional barriers to including Indigenous Knowledge in state and federal management

Systemic and institutional barriers prevent Indigenous Knowledge from being included in or leading management on state and federal land.

These barriers include 1) bureaucratic management structures, 2) racism, 3) unequal power dynamics between Tribes and the state and federal governments, and 4) Tribes’ need to use litigation to hold the state and federal governments accountable for mismanagement. There are two main epistemological barriers that prevent Indigenous Knowledge from being considered on par with Western science: First, Indigenous Knowledge is primarily oral rather than written in books or articles; second, it is often expressed through spiritual or social connections instead of in numbers or Western scientific frameworks. Instead, Indigenous people are expected to translate their Knowledge to be understood by Western scientists. Due to these barriers—barriers acknowledged by Ninilchik community members and explained more fully below—Indigenous Knowledge not only does not lead Alaska land and water management but is excluded almost completely.

Current Alaska and federal land and water management practices prioritize economic benefit, which often puts at risk the state’s land, waters, plants, and animals, along with the humans who depend on them.

These practices continue even as international scientific bodies like the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the International Institute for Sustainable Development find that Western-based land management practices result in more species and ecosystem decline, and that Indigenous care and Indigenous Knowledge are the key to sustainable management. Indigenous Peoples approach the environment as sacred and care for it as they would themselves; while this results in protection of biodiversity, the state of Alaska and the U.S. federal government have still not called on Indigenous Peoples to lead land and water stewardship. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states that Indigenous Peoples have the rights to manage their lands and natural resources due to their connection to that land prior to colonization, but the United States has never formally adopted UNDRIP in a way that is legally binding. Environmental justice principles further call for Indigenous Knowledge and leadership in land and water management.

Without these rights protecting subsistence, Alaska Natives are unable to pass on subsistence knowledge and practices, key aspects of their cultures that are important to promote well-being and protect against the impacts of historical trauma among Alaska Native children, youth, and families.

Due to state and federal land and water management policies and practices, Alaska Natives have limited abilities to practice subsistence and care for their lands, thereby restricting their subsistence practices and harming child and family well-being.

State and federal management practices are based around individualism and fail to account for Indigenous community, cultural, spiritual, and relational perspectives. The NVT’s current subsistence issues are shared by more than 200 other Indigenous Tribal Nations in the state and result from centuries of policy aimed at redefining who Indigenous Peoples are and their relationships to the land.

Although this case study focuses on Ninilchik, the above history demonstrates that state and federal governments continue to limit Alaska Native subsistence rights and land and water management rights—limitations that constitute environmental injustices. These limitations and injustices provide significant reason to revise existing policy and implement new policy around Alaska’s lands, waters, and subsistence rights. While, at the time of this brief, federal officials are currently promoting Indigenous Knowledge and co-management in the 48 contiguous states in an unprecedented way, Alaska still lacks co-management agreements with Native Tribal Nations to manage their lands, waters, and subsistence resources.

V. Findings: Ninilchik Perspectives on Subsistence

These findings are drawn from the author’s study conducted in partnership with the Ninilchik Village Tribe (NVT) in Ninilchik, AK. The research explored how residents of Ninilchik see their community in the future as one that is sustainable, protective of, and providing for members’ well-being. The findings presented here look specifically at participants’ perspectives on subsistence, the cultural and protective value it has for youth, and its importance in food security.

Finding 1. Ninilchik residents rely heavily on subsistence.

In the EFR scenario interviews, one participant explained the importance to Ninilchik of “[k]eeping the subsistence lifestyle, that I think…should be a cornerstone of who we are.”2 This person explained that subsistence is a large cultural aspect of how people in Ninilchik choose to identify. The kinship-based principles of subsistence and understanding plants and animals as relatives is an important perspective that should be a cornerstone and central aspect of being Indigenous, including a kinship approach to stewardship.

Participants explained that food security was not the only reason subsistence was so important to them: They see subsistence cultural practices as an important part of their well-being and spiritual fulfillment and value passing these practices on to their children and grandchildren. One Tribal member summed up the importance of subsistence to their identity and well-being: “I can’t live without a king salmon. I can’t live without a moose. I can’t live without a clam. Okay, that’s me. That’s my DNA.”3 Past studies in Ninilchik by the ADF&G document an average household harvest of 439.5 pounds of subsistence resources and a per person fish harvest of 81 pounds in 1998 and 82 pounds per person in 2002.

Finding 2. Cultural continuity is important to Ninilchik residents, and youth learn subsistence practices from their parents, grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins, and the Tribe.

The Tribe won a Native Connections grant (from 2016-2021) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) for one million dollars to reduce suicide and substance abuse; this grant helped them develop the youth education leadership program (YELP), which draws on Indigenous culture as a protective factor to address suicide and youth’s substance abuse challenges. The YELP program takes youth out on the land to learn subsistence activities such as using a net across the river to fish for salmon or digging razor clams on the beach across the Cook Inlet from Ninilchik. Because subsistence is more than just gathering food, youth also learn to clean and process the fish and clams through canning, and to smoke the salmon. They then provide the processed food to Elders in the community who, due to age-related challenges, can no longer practice subsistence themselves. This sharing of food and providing to the community—especially to Elders—is an important part of what subsistence means to Indigenous people.

Finding 3. Subsistence practices are protective for many Ninilchik families; by practicing subsistence, people feel a sense of self-worth and cultural identity.

Many Tribal members’ Indigenous identity and well-being are tied to subsistence. Sadly, colonization resulted in substantial cultural loss in the community and subsistence is a central aspect of culture that Tribal members hold dear. As one participant explained, “Our culture … what I was taught and how I was brought up was what you should do to survive in this environment. And, you know, we don’t have songs necessarily or a language other than Russian. We don’t have a bunch of dances, regalia, things like that that other Tribes have.”4

The right to practice subsistence is central to the well-being of Indigenous residents in Ninilchik and passing on that cultural practice to future generations is of the utmost importance. Interviewees explained that this cultural continuity requires the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in subsistence management for the sustainability of animals, plants, land, and water.

Finding 4. Many Ninilchik residents feel that land management decisions do not value, respect, or see as legitimate the science inherent in Indigenous Knowledge.

One Indigenous participant addressed how the failure to include Indigenous Knowledge in management decisions made them feel: “No one wants to listen to the people that actually are out here … They don’t listen. They’re not listening to me. I mean, I don’t have a college education, so, that goes right out the window right away, anything I say. I’m too dumb for them to listen.”5 This participant emphasized that officials responsible for decision making were located far from the community and chose to only incorporate the input of scientists with degrees into management decisions. This participant went on to explain their frustrations with the state management making it difficult to practice subsistence:

“Sue the shit out of the state and the feds and tell them to shut it all down. If subsistence can’t happen and the subsistence users cannot go out there, they’re causing such a burden on the fish [emphasis the author’s], then shut it down. Shut sports fishing down. Shut commercial fishing down. And shut the guides down [sports fishing guides] … I’m pretty sure, probably within two weeks, the state would go, hmmm, we really should figure this out because there’s a lot of people that are pissed. And then they’d figure it out. But the problem we have is we can’t hold them [the state of Alaska] accountable.”6

Management decisions are in fact made by the state or the Board, depending on what land is in question.

Finding 5. Tribal members explained how NVT has fought legal battles, just like other Tribes, to maintain their subsistence rights and have their sovereignty respected.

From 2006 to 2016, NVT struggled for recognition of their rural subsistence rights (granted to them through ANILCA) so they could fish for Ninilchik residents who were unable to fish for themselves (Alaska Native and non-Native). NVT sought to fish on the federal waters of the Kasilof and Kenai Rivers with a set net spanning partway across the river waters. They hoped to catch the number of fish allowed per permit (at the time, 25 sockeye salmon per head of household with five additional for each family member) and estimated that NVT would fish for 2,000 sockeye salmon for the year. The Ninilchik Traditional Council (NTC), the Tribe’s governing body, took a proposal to the Southcentral RAC of the Board in early 2014 to fish on the rivers; they received approval for the Kasilof River in 2015 but were denied the right to fish in the Kenai River.

The NVT sued the federal government for rights to fish in the Kenai River, which were granted by experimental permit in 2016 and have been allowed since. ADF&G and USF&W biologists had argued against the set gillnet (a net with holes for different sizes of fish to pass through or be caught in by their gills) in the Kenai, claiming that the net would prevent fish from being able to swim up the river to spawn, yet remained silent regarding the commercial fishermen under jurisdiction of the state of Alaska and ADF&G who use gillnets (both drifting and set gillnets) at the mouth of the river—despite the fact that these fishermen take 98 percent of the yearly catch, compared to just 2 percent taken by subsistence fishing. Ninilchik sought to fish on the upper federal waters of the river while the mouth of the river was managed by the state of Alaska. One participant explained how Indigenous understandings of fishing for subsistence differed from commercial fishing: “Fishing became a way to get money to buy food instead of a way to just get food and everybody got really excited about that … subsistence is basically outlawed on the Kenai Peninsula which is bizarre.”7 This puts Indigenous Peoples at risk of not being able to practice subsistence and pass on their culture to youth.

Finding 6. Ninilchik residents worry about the ways that fish and wildlife are managed in the Ninilchik area and consider current management practices to be unsustainable, observing that Indigenous Knowledge is not included in subsistence management.

Participants mentioned that NVT had notified the state repeatedly over the years that razor clam population numbers were diminishing on the local beach (especially after a strong storm in 2010 harmed the population), but the state continued to allow clamming not only for Ninilchik residents but also for urban residents from Kenai, Soldotna, and Anchorage—totaling over half a million people. Once clams were half their original physical size and greatly reduced in number, the state closed the beaches, which have remained closed since 2014. As one participant said, “Put the state in charge of the mosquito population and it’ll be gone. If you want to kill something off, put the state in charge of managing it. They managed to kill off our clams.”8

This loss of ability to clam on their home beach was devastating to many residents who had harvested clams for generations and had cultural practices around harvesting and processing, along with recipes to enjoy clams together. Excluding Indigenous Knowledge from management threatens species, food security, and the ability for Alaska Natives to pass down their culture, all of which promote their well-being. It is not only Indigenous residents that want Indigenous Knowledge included in management decisions: A non-Native participant and resident of Ninilchik described how they see NVT participating in fish and wildlife stewardship:

“The state and the federal government should step out and let the Tribe do what the Tribe does. They’ve managed that resource since the beginning of time. They understand it. They understand the reproductive cycles. They understand the lifespan. They understand the climates that are going to be involved. They have history, and they can look back and they can see those cycles. … The Tribe recognized the problem [low counts of clams, fish, and/or animals] a long time ago, 90 percent of the time. They don’t get surprised. They see it coming. You hear the Elders whispering about it and talking about it and nobody listening to them. You’ve got to listen to the Elders. They’re the memory in the room.”9

In 2023, for the first time since 2014, ADF&G allowed sport razor clamming in the Ninilchik area for all state residents (not only for those who rely on clams for subsistence) for four days over the July 4th weekend, allowing every person to keep the first 15 clams they dig. While the ADF&G’s website states that they conduct abundance surveys, hand digging surveys, and maturity assessments yearly to assess the population, clams are still not reaching previous sizes seen prior to beach closure and the beaches will likely be closed again in 2024 and 2025. NTC President Greg Encelewski explained the Tribe’s perspective on the opening, which received little press coverage (it was only found in one of more than 10 media articles on the topic) and is not present on the ADF&G Cook Inlet Razor Clam Sock Assessment page: “All of our members so far are just disgusted with the opening. We feel that it’s way too soon. The clams have not recovered. The impact is going to be tremendous on the beaches whether they think so or not. We’re going to have just about everyone in Anchorage down here to dig that weekend on the Fourth of July. And I think that you start multiplying the numbers and the families, it’s going to really impact them.” With an Anchorage population of around 288,000 people and an additional 59,000 on the Kenai Peninsula—and with every family member digging getting up to 15 clams—the beaches could be significantly impacted.

Among the responses from the optimistic future scenario, some participants talked about Tribal sustainable stewardship practices based on Indigenous Knowledge resulting in flourishing fish and wildlife populations. Participants did not feel that the Board or state listen to Indigenous Peoples or include their Knowledge in management, even though NTC’s president is on the Southcentral RAC to the Board. Instead, they see management decisions based on politics and money, not on species counts and ecology. One participant explained, “Somehow, you’re going to have to get away from political management. … If we want a resource to thrive, we have to have good nonpolitical management and the state is just 100 percent political. So, when they’re managing, they’re managing by, ‘What does the sport fishing industry want?’ They’ll get a call from the commissioner, from the governor, and say, ‘No we want this, sportfisherman are saying close this down.’ So, politics unfortunately plays too much in state management.”[10] This power differential leads to a lack of protection for subsistence. Over half the 30 participants discussed the need to include Indigenous Knowledge—based on millennia of observations—in management on both state and federal lands and waters. Currently there is no co-management between the Tribe, federal government, and state of Alaska practiced in Ninilchik. Additionally, none of the land in the Ninilchik area is held in trust by the federal government and seen as Indian country or reservation lands, which means that the Tribe does not have the authority to manage natural resources.

Finding 7. Participants emphasized the importance of subsistence for food security, cultural continuity, and individual and community well-being.

Participants also emphasized NVT’s important role in drawing on the community’s self-determination to advocate for subsistence rights. State and federal land management practices restricting subsistence are examples of modern-day colonization. Decolonization and anti-racism in land management are necessary for the sustainability of species so that subsistence can continue to be practiced. An anti-racist approach must look at systemic polices, structures, and norms to dismantle racism. A systemic approach seeks to not only change beliefs and behaviors but also to change policies, structures, laws, and norms. Ultimately, Alaska Native subsistence use practices in Ninilchik are based on relational understandings to the world and a desire to care for the earth in a way that will allow it to provide for the well-being of children and families into the future. This care is not economically motivated but based on well-being and the overall health of the entire ecological system, of which humans are a part.

Ninilchik Village Tribal Elder Eric Kvasnikoff showing tribal staff and youth how to hang a subsistence gillnet.

VI. Policy Recommendations to Reduce Barriers to Subsistence for Alaska Natives

The Indigenous people quoted in this paper have explained how subsistence rights are critical for their well-being and provide both cultural and spiritual connectedness and food security. Yet, through ongoing colonization, the federal and Alaska state governments currently wield all power over land and water ownership and management on the vast majority of land in Alaska. This brief has shown the unique interrelationships between people, culture, place, and policy to demonstrate how law and policies have immediate impact on Indigenous children and families’ well-being. Indigenous Peoples seek justice for the land and waters, to care and nurture them back to health and create a space for not only humans but our nonhuman kin and relatives to live; they seek to maintain a sense of responsibility as humans to nurture the earth, with an approach based around gratitude and awareness of all the earth provides. Federal and state governments can better serve all people living in Alaska by listening to Alaska Native Tribal Nations and Indigenous Knowledge, and by allowing their input to inform sustainable stewardship practices so that the state’s lands, waters, animals, plants, and natural life are healthy for everyone to appreciate and enjoy.

Findings from the author’s study demonstrate the need for Indigenous Knowledge to lead land and water management and identify the barriers to including that Knowledge in management decisions. Additionally, the findings point to Indigenous culture as a protective factor in the lives of Indigenous children, youth, and families.

The policy recommendations below are grounded in the research and built on the author’s findings. They explain how to reduce the barriers Alaska Natives face in practicing subsistence and demonstrate how to increase sustainable management of the lands and waters through leadership by Indigenous Knowledge.

In the remainder of this section, the author first articulates an ideal outcome from Alaska Natives’ perspective—a return of management over lands and waters to Tribal Nations—and then identifies incremental recommendations that can work to address barriers toward subsistence and (by extension) Alaska Native well-being. Any policy changes must happen in discussion with Alaska Native organizations and Tribal Nations.

The ideal: Tribal Nations sustainably steward lands and waters

Ideally, the Alaska state and federal government would restore decision-making power over lands and waters to Alaska Native Tribal Nations. Under such an arrangement, whereby Tribal Nations would receive governance rights over land and waters—consistent with the Land Back and Water Back movements advocating for decolonization—non-Indigenous people with homes or business on such lands would not be required to vacate; however, this arrangement would facilitate sustainable stewardship, co-management, nurturance practices, self-determination, and sovereignty. This sovereignty includes cultural and political sovereignty, which are necessary for protecting Indigenous ways of life and subsistence practices, extending far beyond economic needs. In Ninilchik, this would allow the NVT to manage their lands and waters so that clams, salmon, and other populations they harvest will exist for generations to come.

This approach has been successful in a variety of settings, as Indigenous Knowledge and Indigenous-led stewardship are crucial for conservation, use, and climate change mitigation: 1) The Amah Matsun people of central California have memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with federal, private, and state actors to govern 140,000 acres of their traditional territory—across state and federal parks—to steward, conserve, and access the land for cultural purposes; 2) the Yurok and Karuk Tribes of Oregon and California have worked with the U.S. Department of the Interior to remove dams to revitalize fish populations for cultural practices; 3) as of 2022, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes finished negotiations with the U.S. Department of the Interior to assume responsibility over a historic bison range in Montana and the reintroduction of bison through a trusteeship with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Along with the previous examples of regained governance over traditional lands and waters, the Department of the Interior is continuing to pursue co-stewardship and land/water back in the contiguous United States (not Alaska, as of yet): 1) Bears Ears National Monument in Utah has a formal co-management structure with the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and five Tribes of the Bears Ears Commission; 2) in Virginia, the Rappahannock Indian Tribe received 465 acres of their land back within the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge to conserve; and 3) the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery was transferred to the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho with continued support to be provided by the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Co-management agreements around land and water management with Tribes in Alaska are extremely limited, with short-term projects or with Tribes providing tours and not actually managing the land. Co-management is instead based on various councils and commissions around birds, walrus, seals, whales, polar bears, and flora and fauna (without the sovereignty that comes with Tribal engagement). The Congressional Research Service has written a report (2023) for Congress on Tribal co-management, which explains how co-management on federal lands may help achieve congressional priorities as well as draw on Indigenous Knowledge. Organizations like the Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission and the Indigenous Sentinels Network are formed of multiple Tribes in Alaska that use local Indigenous Knowledge to monitor environmental issues, lands, waters, and animals and work with federal and state management bodies.

These different arrangements address co-management, co-stewardship, and conservation; the latter has historically been harmful for Alaska Native subsistence practices, cultural continuity, and food security. For example, as worldwide organizations advocate against ivory to save African elephants, the public has come to conflate Alaska Native walrus ivory with elephant ivory. This public perception harms Indigenous Peoples’ food security, even though walruses are sustainably harvested in Alaska—primarily as subsistence food, with their ivory tusks being for secondary artistic use. Other organizations that work to save whales and seals from commercial harvesting—a practice these organizations previously conflated with subsistence use—have listened to and learned from Indigenous populations the importance of Indigenous subsistence use and are working to make further amends. In Alaska, federal and state-led conservation efforts have historically “locked” Alaska Natives out of their traditional subsistence harvesting areas. Past legislation barring motorized vehicles and equipment, such as the 1964 Wilderness Act, harmed Indigenous access by restricting methods of transportation they had come to depend on. Finally, the Bureau of Land Management is currently proposing a new rule to displace some federal multiple use land in Alaska with conservation land.

Indigenous Peoples in Alaska lost 90 percent of their land to colonization and, due to ANCSA, the vast majority of Alaska Native Tribal Nations are landless, with land held by Alaska Native regional and village corporations. Although restoring decision-making power over lands and waters to Alaska Native Tribal Nations is ideal, this would require a substantial shift in policy and law. However, state and federal policymakers can take numerous concrete steps toward helping Indigenous Knowledge holders feel heard and respected, address better land and water management, create space for Alaska Native subsistence, and allow cultural continuity for well-being. The following actionable recommendations offer possibilities for Indigenous Tribal Nations’ advocacy, as well as incremental but concrete decisions that policymakers can take without tackling centuries of colonization and federal Indian law all at once. The recommendations stem from and are grounded in the research project described in this brief and conducted in partnership with NVT and represent levers that will help protect Alaska Native children and family well-being.

Incremental recommendations to address barriers to subsistence

Recommendation 1: Federal and state governments should prioritize Alaska Native subsistence use through investment, policies, and statutes.

Participants in Ninilchik explained that, as a result of extensive colonization, subsistence—an intricate part of their well-being—is one of the few aspects of their culture to which they have been able to hold. Elders place great significance on passing on subsistence culture to the youth to ground them in who they are and protect their culture.

Federal policymakers can begin to prioritize healing and protective factors for Alaska Native children and families by prioritizing Alaska Native subsistence through the following strategies:

- Increase federal funding for Alaska Native Tribal Nations around social development, culture, and language, using a noncompetitive funding process so that Indigenous children and youth can learn about and practice subsistence.

- Increase funding to the federal Office of Subsistence Management as the staff works with the Federal Subsistence Board and the Alaska Native Tribal Nations.

- Convene a presidential working group to address Alaska subsistence reform through Alaska Native leadership grounded in Indigenous Knowledge.

- Amend the definition of rural in ANILCA to include Alaska Native communities that need subsistence use not only for food security but for cultural and spiritual needs.

- Amend ANILCA to add an Alaska Native priority alongside the rural priority, which would allow urban Alaska Natives traveling to traditional rural home areas to engage in subsistence.

- Amend ANCSA to repeal the extinguishment clause that outlawed subsistence and restore Alaska Native subsistence rights on ANCSA lands.

- Revise how “Alaska Native” is defined in federal law; specifically, remove the one-fourth blood quantum from federal laws (including ANCSA, ANILCA, MMPA) and replace it with traditional kinship principles and use-determinations by Tribal Nations to protect Alaska Native children from being excluded from certain subsistence practices.

The Alaska state government can also play a role in prioritizing subsistence practice in their own policies, and in their implementation of federal laws. One way to do so is by adding an Alaska Native subsistence priority as a state of Alaska constitutional amendment.

Recommendation 2: Federal and state land and water management in Alaska should be led by Indigenous Knowledge holders.

As Ninilchik participants explained, ignoring Indigenous Knowledge in stewardship puts the lands and waters in great peril as species decline and are overharvested. Ninilchik residents are still mourning the loss of their razor clam population; this ecological grief is leading to extensive cultural loss as the community is not able to pass on the tradition of harvesting, processing, and cooking clams to their youth. Indigenous Knowledge—with its generations of observation and daily monitoring—is valid and valuable as science.

Federal strategies for engaging Indigenous Knowledge in management include:

- Implement the recent guidance and implementation memos from OSTP on including Indigenous Knowledge in federal decision making and management.

- Revise policies and regulations to include Indigenous Knowledge as “best available science.”

- Restructure the Federal Subsistence Board to increase its use of Indigenous Knowledge by including Alaska Native representatives as voting members on the board. Likewise, value Indigenous Knowledge holders along with Western scientists as experts on subsistence management.

- Have Alaska Native Tribal Nations manage lands and waters on ANCSA lands.

The Alaska state government can demonstrate that it values Indigenous Knowledge in subsistence management with the following actions:

- Issue an executive order that requires or promotes the use of Indigenous Knowledge in management decisions and includes it as a “best available science.”

- Establish a state-level division at the Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G) that prioritizes Indigenous Knowledge in land, water, and resource management. This could be achieved by reinstating the Subsistence Division, which state leadership recently reduced to a smaller and less impactful section, or by establishing a new Indigenous Knowledge Division.

- Develop policies through ADF&G that recognize the validity of Indigenous Knowledge and develop regulations that require the Board of Fisheries and Board of Game to incorporate recommendations from Indigenous Knowledge holders.

- Place both a fishery manager from the Commercial Fisheries Division and a subsistence (or Indigenous Knowledge) manager on each fisheries management team in the ADF&G to work in cooperation.

- Provide both current Western science-based reports and Indigenous Knowledge reports at management presentations to demonstrate both perspectives at Board of Fisheries and Board of Game meetings.

- Include Alaska Native representatives from each region on the state Board of Fisheries and Board of Game as voting members so that subsistence use decisions are made according to Indigenous Knowledge and subsistence users’ needs instead of political goals.

Recommendation 3: Tribal Nations, the state of Alaska, and the federal government should create co-management structures for sustainable subsistence management.

Ninilchik participants explained that, without cooperation between all three entities, different parts of the same river are managed differently, which does not work for sustainable management. As an example, the state manages the mouth of the river and the federal government manages farther up the river, which makes it difficult to ensure that enough fish can travel upriver for subsistence use. Currently, co-management and cooperative agreements in Alaska are solely between Indigenous organizations and the federal government. Tribal sovereignty is not included in co-management structures. The U.S. Department of Interior and Department of Agriculture Order No. 3403 has led to increasing co-management agreements in the contiguous United States with Tribal Nations, so this outcome is very plausible in Alaska. The state and federal governments do not always cooperate in management and the federal government criticizes the state for failing to protect subsistence. There are multiple ways forward and the recommendations below are organized from the most accessible to the most difficult to accomplish; all move incrementally toward co-management and/or management led by Tribal Nations.

Federal strategies for supporting the effective co-manage of lands and waters include:

- Implement Order No. 3403 in Alaska to create co-stewardship agreements of federally held land with Tribal Nations. Include funds for Alaska Native Tribes to be able to participate in co-management.

- Issue an executive order to mandate co-management on federal lands. Amendments would require allocating noncompetitive funds for Alaska Native Tribes to participate in co-management.

- Develop a process to engage with Tribal Nations and the state of Alaska in co-management for the entire state so that upstream and downstream waters and lands have congruent and sustainable management guidelines.

- Simplify the fee-to-trust process, implementing the proposed new regulatory process and providing funding for Tribal Nations to go through the application process. If Tribes put land into trust, creating Indian Country/reservations in Alaska, Tribes would be able to manage their natural resources on their lands, much like Tribes with reservations in other states.

- Amend the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act to add seats for Alaska Natives on the North Pacific Fishery Management Council.

- Transfer management of land and waters to Tribal Nations through compacting or contracting, a precedent established by the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.

- Amend ANCSA, ANILCA, and the MMPA to establish co-management and consultation requirements.

The governor of the state of Alaska can also issue an executive order requiring co-management with Tribal Nations. State leaders should also consult with Alaska Native organizations and Tribal Nations on how to increase Alaska Native participation in state management. Finally, the state must engage with Tribal Nations and the federal government in co-management for the entire state so that upstream and downstream waters and lands have congruent and sustainable management guidelines.

Ninilchik Village Tribal children pick salmon from a subsistence gillnet.

VII. Conclusion

The NVT, along with many other Tribal Nations and Indigenous organizations in Alaska, are calling for their voices and Indigenous Knowledge to contribute to stewarding Alaska’s lands and waters. This participation would be directly aligned with the roles of Tribal Nations in the contiguous United States and Indigenous Peoples throughout the world, as clarified in United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. International scientific bodies like the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the International Institute for Sustainable Development agree that Indigenous Knowledge should lead land and water stewardship. Reports from these organizations have found that Indigenous Peoples’ lands contain 80 percent of the earth’s remaining biodiversity, that land stewarded by Indigenous Peoples has seen less decline in number of species and ecosystem quality than other lands, and that “Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge and knowledge systems are key to designing a sustainable future for all.” Another study found that, when local and Indigenous Peoples led land and water conservation projects, they had better ecological and social outcomes: 56 percent of Indigenous-managed projects had positive outcomes, compared to only 16 percent managed externally.

Indigenous people, with their generations of Indigenous Knowledge acquired through living side-by-side with the natural environment, are the key to sustainable stewardship. It is important that Indigenous people are not only leaders, but that policies and practices change.

Regardless of the extensive evidence to support Indigenous-led stewardship, and the need for greater biodiversity to have a sustainable future for all, the state of Alaska and federal governments hold onto the land for its economic resource abundance. Without returning land management and sovereignty to Indigenous Peoples, the state will continue to see declines in species and ecosystems. The fear of losing fish and animal kin, upon whom Indigenous Peoples rely for subsistence, is a fear of not only food insecurity but of cultural and spiritual loss as well. As Inuit Greenlander Aqqaluk Lynge explains, “The threat that all of the Arctic’s Indigenous Peoples feel to their culture, their language, to their heritage and to their environment is intimately connected to the fear we all have regarding our inherent rights to hunting, fishing, and gathering.”

Subsistence represents the continuity of culture and the passing on of millennia of acquired protective Indigenous Knowledge. Current state and federal land and water management policies and practices limit Alaska Native subsistence and prevent Indigenous people from passing on preventive and protective cultural practices to their children and youth, putting these young people at risk. In 2002, in her previous capacity as chair of the Alaska Federation of Natives Subsistence Committee in 2002, Rosita Worl (now president of the Sealaska Heritage Alaska Native nonprofit in Southeast Alaska) said:

“Without a subsistence economy, hunger would be the norm in Alaska Native and rural communities. … [but] Alaska Native people believe that they have a spiritual relationship to the animals and to the wildlife … sharing is key to subsistence and is key to the survival of Native societies.”

Arthur Lake, president of the Association of Village Council Presidents in Alaska, explains: