Because families are the first nurturers and educators of their children, it is helpful for policymakers and other stakeholders to understand how family characteristics, the activities in which families engage, and their neighborhood circumstances are associated with preschool children’s health and readiness for learning. The analyses presented in this brief examine the associations between various family and neighborhood factors and the extent to which a child is reported to be healthy and ready to learn, using data from the 2017 and 2018 waves of the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) for children ages 3 to 5.

Key findings

Several key factors are consistently related to how healthy and ready to learn a preschool child is found to be, even when we take account of (statistically control for) social, economic, and demographic factors.

- Family characteristics and activities. Parents or caregivers who describe their families as having greater strength to face problems, more consistent bedtime and meal routines, and less anger toward their child report having children who are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn.

- The parent’s physical and emotional well-being. Parents who describe themselves as having excellent or very good mental or emotional health and who describe themselves as having excellent or very good physical health report having children who are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn.

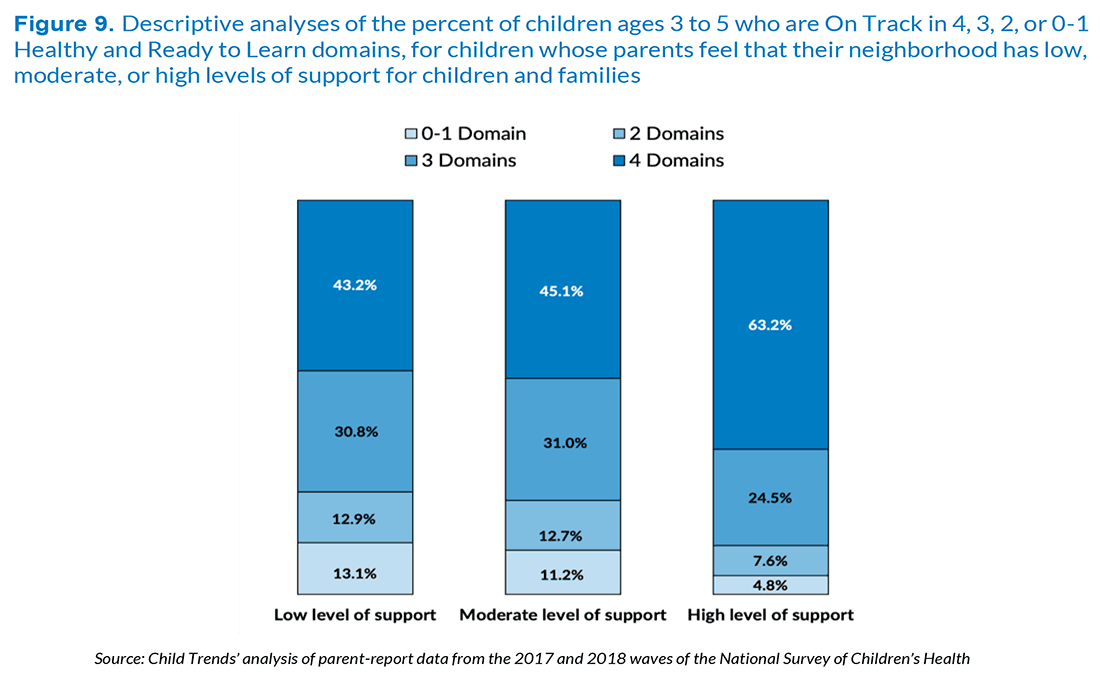

- The family’s neighborhood. Children who live in neighborhoods with few amenities and more problems are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn than other preschoolers. The reverse is true among children whose families live in neighborhoods that are supportive of families. Neighborhood supportiveness has a larger association with whether a preschooler is healthy and ready to learn than the measures of neighborhood problems and amenities.

About the survey and measure

Parents or caregivers who participate in the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) respond to a set of items about their child’s development. From these responses, measures of each child’s health and readiness to learn were developed for four domains: self-regulation, physical health/motor development, early learning, and social emotional competencies. Specifically, with respect to their development, HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA MCHB), with Child Trends, identified children as “On Track,” “Emerging,” or “Needs Support” in each of the four domains. In addition, an overall summary National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn (HRTL) was defined according to whether children were healthy and ready to learn in all four domains, in three domains, two domains, or in zero or one domain. This brief uses the metric of On Track in all four domains as representative of being “Healthy and Ready to Learn.”

Analyses assess a range of characteristics related to being On Track in all four domains of the HRTL measure.[1] These family and neighborhood characteristics are also assessed in the NSCH and include family strengths, family routines, parent physical and mental/emotional health, parent anger, the parent’s emotional support for parenting, neighborhood amenities and challenges, and neighborhood supports for childrearing. Associations or differences described in this brief reflect statistically significant differences as indicated by a p-value < .05. Furthermore, we conducted analyses that examined the association between each characteristic and being On Track in all four domains that controlled for social, demographic, and economic factors, including child race/ethnicity, sex, parental education, family structure, and family income. These findings help parse the association of each characteristic with HRTL from other influences on child development. Findings from multivariate analyses are reported in the text. Detailed tables of findings are available upon request.

This brief also presents findings related to being On Track in each of the four domains of the Healthy and Ready to Learn measure (HRTL); further detail on the HRTL measure can be found in Appendix A. Details on each covariate, including item wording and response options, are available in Appendix B. Findings for each of the measure’s four domains are presented in Appendix C. Two related briefs, forthcoming in 2020, provide additional analyses drawn from HRTL data: One brief examines the association between children’s scores on the HRTL measure and their demographic, social and economic backgrounds; and the other explores the association between the HRTL measure and child characteristics.[2]

The Purpose of Healthy and Ready to Learn

As more communities, states, and philanthropists invest in young children and their families during the earliest years of life, there is a critical need for measures of well-being and school readiness that indicate how young children are faring at the local, state, and national levels. The HRL measure was not designed to replace current measures of child development, well-being, or kindergarten readiness; rather, the measure is intended to fill a gap in understanding of children’s development and school readiness from ages 3 to 5, during the years prior to kindergarten entry.

Findings

Download

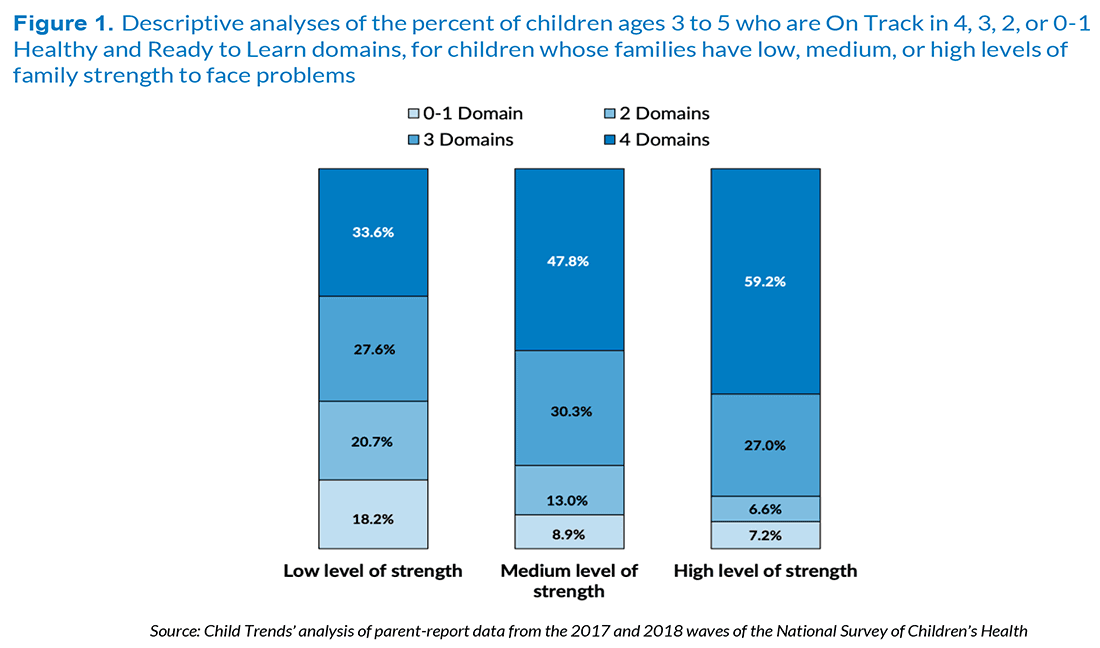

Preschoolers whose parents report medium or high levels of family strength to face problems are substantially more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than preschoolers whose parents report a low level of strength.

Most American children live in families that possess many strengths, and these strengths are associated with a host of positive outcomes.[3] Family strength is assessed by four questions in the NSCH that were developed to ask the parent or the parental caregiver to describe how their family faces problems; specifically, the survey asks how frequently family members talk together, work together, know they have strengths to draw on, and are able to stay hopeful when they face problems. The frequency for each of the four reported strengths was summed, as described in Appendix B, and scores were defined as low, medium, and high levels of strength.

Analyses indicate that children are more likely to be On Track when their families feel they have the strength to face problems. That is, children whose parents report that their family has high levels of strength for facing problems are much more likely to be healthy and ready to learn in all four developmental domains. Also, children in families that describe themselves as having low levels of strength for facing problems are far less likely to be On Track in all four domains (see Figure 1). Specifically, 34 percent of children in families with a low level of self-described strength are healthy and ready to learn in all four domains, compared with 48 percent of children in families with a medium level of strength and 59 percent of children in families with high levels of strength. Corresponding to this pattern, approximately half of children in families with low levels of strength are On Track only in zero or one domain, or in two domains. These associations remain statistically significant when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure.

Detailed descriptive analyses are reported in Appendix C. They indicate that level of family strength is related to being On Track in each of the four HRTL domains, individually, as well as the overall summary HRTL measure; however, family strength is most strongly associated with readiness in the self-regulation and social-emotional domains.

Related Content

- Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Preschoolers’ Experiences

- Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Socioeconomic Conditions for Preschoolers

- Comparing the National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn with Other Well-Being and School Readiness Measures

- A promising new measure of kindergarten readiness

- National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn

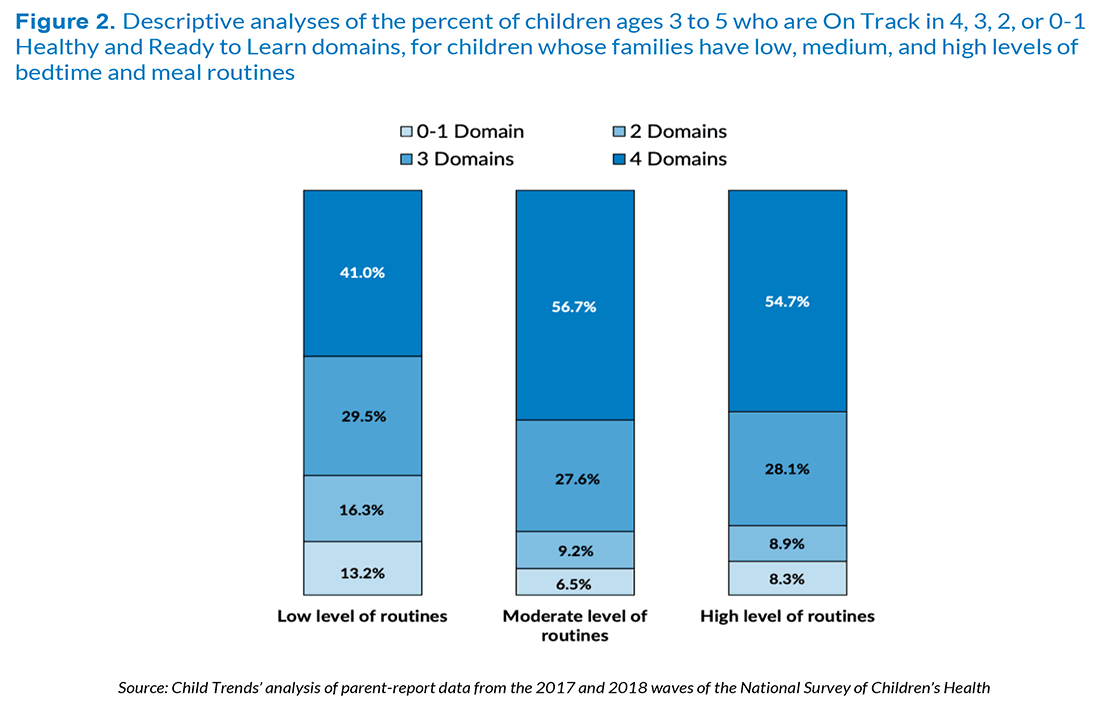

Preschool children in families with routines for bedtime and meals are much more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than children in families without such routines.

Family routines have been found to be consistently related to many aspects of children’s positive development.[4] Two items that assess family routines in the NSCH were combined for this analysis: having meals with all family members and having a regular bedtime (see Appendix B for items and coding).

Figure 2 shows that a low level of family routines is related to being On Track in fewer domains. Specifically, as shown below, 41 percent of children in families with few routines are On Track in all four domains, compared with 57 percent of children in families with moderate levels of routines and 55 percent in families with high levels of routines. Similarly, children in families with fewer routines are more likely to be On Track only in zero or one domain or in two domains. These associations remain statistically significant when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure.

Detailed descriptive analyses reported in Appendix C indicate that children in families with moderate or high levels of routines are more likely to be On Track for three of the four individual HRTL domains—early learning, social-emotional, and self-regulation—but not in the health domain.

Turning to the individual domains, the association between Routines and being On Track is substantial for the Early Learning, Social-Emotional, and Self-Regulation domains, but not for Physical Health (see Appendix Table).

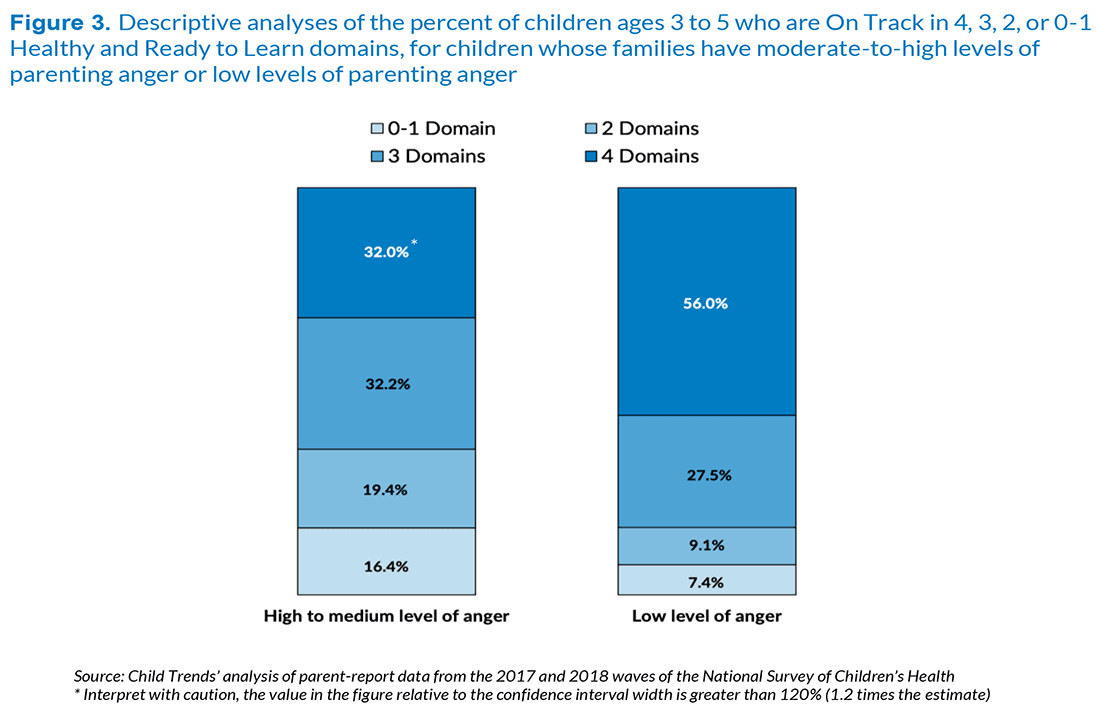

Preschool children whose parents report a moderate or high level of anger with their child are considerably less likely to be healthy and ready to learn than their peers with parents who report a low level of anger.

Parent anger may undermine children’s development of appropriate social-emotional and self-regulation strategies; less is known regarding the link between parent anger and children’s school readiness, broadly.[5] Parent anger is assessed in the NSCH by an item that asks parents or caregivers how frequently they feel angry with their child. Relatively few parents reported frequently feeling angry; therefore, families were coded as having moderate or high levels of anger or having low levels of anger.

The child’s status on the HRTL measure is strongly associated with the parent’s report of feeling angry. Only 32 percent of children whose parents describe high or moderate anger are found to be On Track in all four domains of the measure, compared with 56 percent of the children whose parent indicates a low level of anger. While the proportion of children ready in three domains is similar across the two groups, the proportion of children who are ready only in zero or one domain, or in two domains, is considerably higher when parents feel moderate or high levels of anger. This association remains statistically significant when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure.

Detailed descriptive analyses reported in Appendix C indicate that children whose parent reports frequently feeling moderate to high levels of anger with the child are less likely to be On Track in each of the four individual HRTL domains, and not just in the overall HRTL measure.

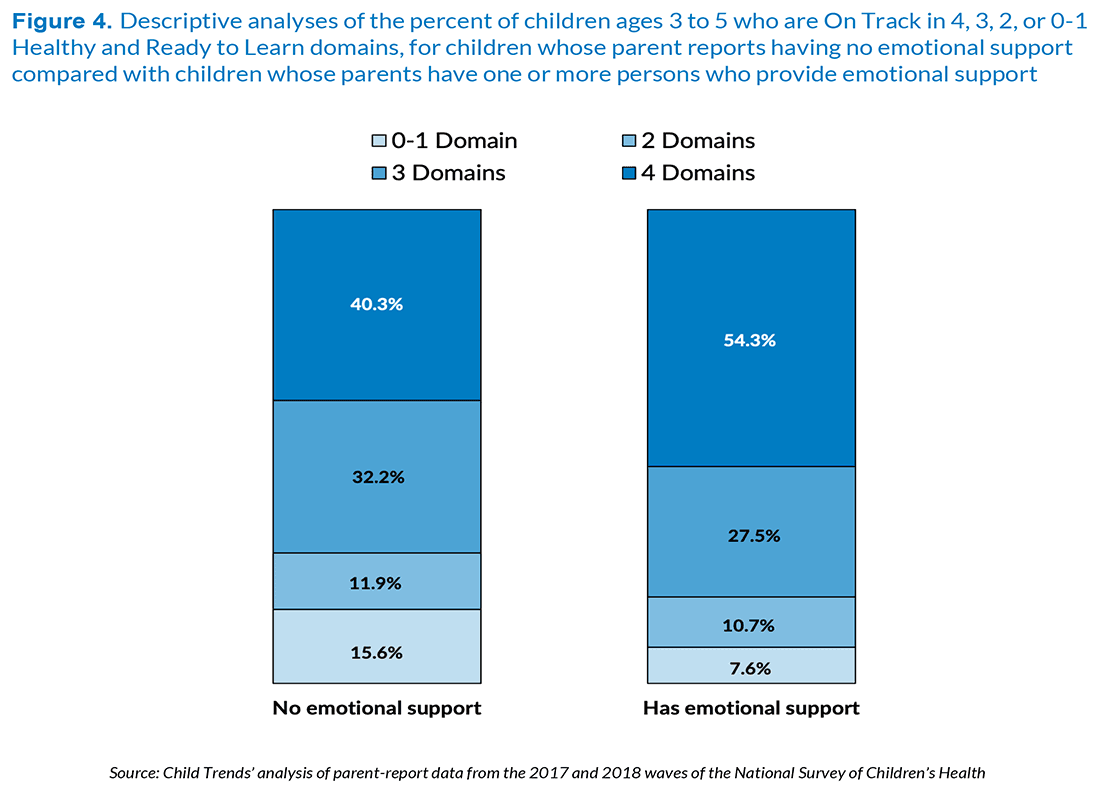

Preschool children whose parents report that they have emotional support for their parenting are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than preschoolers whose parents lack this emotional support; however, this association does not hold when we account for socioeconomic factors.

Emotional support is a key protective factor for parents, as it can promote positive parenting in the face of adversity.[6],[7] An item in the NSCH about parent emotional support focuses on the previous 12 months; it asks the parent whether there was someone they could turn to for day-to-day emotional support with parenting or raising children.

Most parents reported that there was a family member or a professional to whom they could turn for parenting support; 54 percent of the children of these supported parents were found to be healthy and ready to learn in each of the four domains, compared with 40 percent of the children whose parent did not have someone to whom they could turn. Differences are more modest for children who are healthy and ready to learn in three or two domains. However, children whose parent has no one to turn to for parenting support are twice as likely to be On Track in zero or one domain, compared with parents who do have parenting support, at 16 percent compared with 8 percent. However, when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure, this association is no longer statistically significant, suggesting that the association reflects socioeconomic factors.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that a parent’s report of having emotional support is associated with their child being On Track in all four of the individual HRTL domains, but the association is least strong for the early learning domain (see Appendix C).

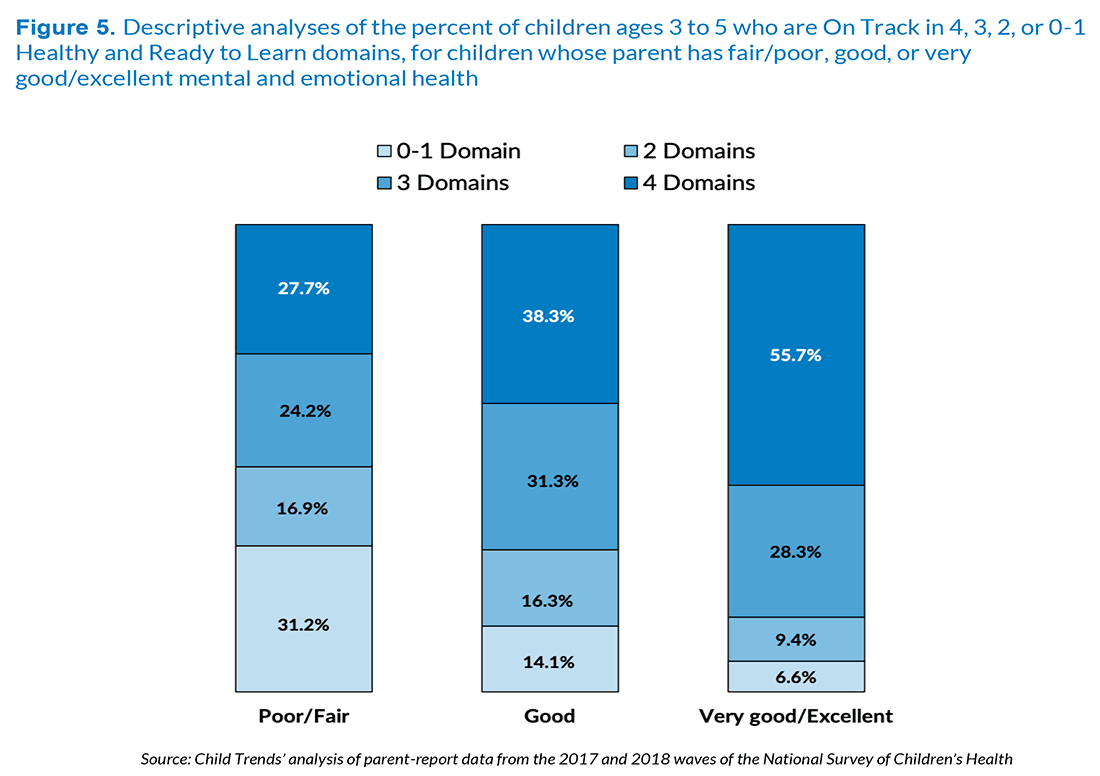

Preschool children are more healthy and ready to learn when their parent’s mental and emotional health is better.

Research suggests that parental mental and emotional health is a key predictor of children’s school readiness because of its links to supportive parenting, emotion socialization, and engagement in learning activities.[8],[9] Parents interviewed in the NSCH reported whether they felt that their own mental and emotional health was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. For this analysis, these responses were collapsed into three categories, shown in Figure 5.

Among preschool children whose parent reported that their own mental or emotional health is poor or fair, only 28 percent are On Track in all four HRTL domains, compared with 38 percent among children whose parent reported that their mental or emotional health is good and 56 percent among children whose parent reported that their mental or emotional health is very good or excellent. These associations remain statistically significant when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that the parent’s mental and emotional health is related to their child being On Track in all four of the individual HRTL domains (see Appendix C), not just on the overall HRTL measure.

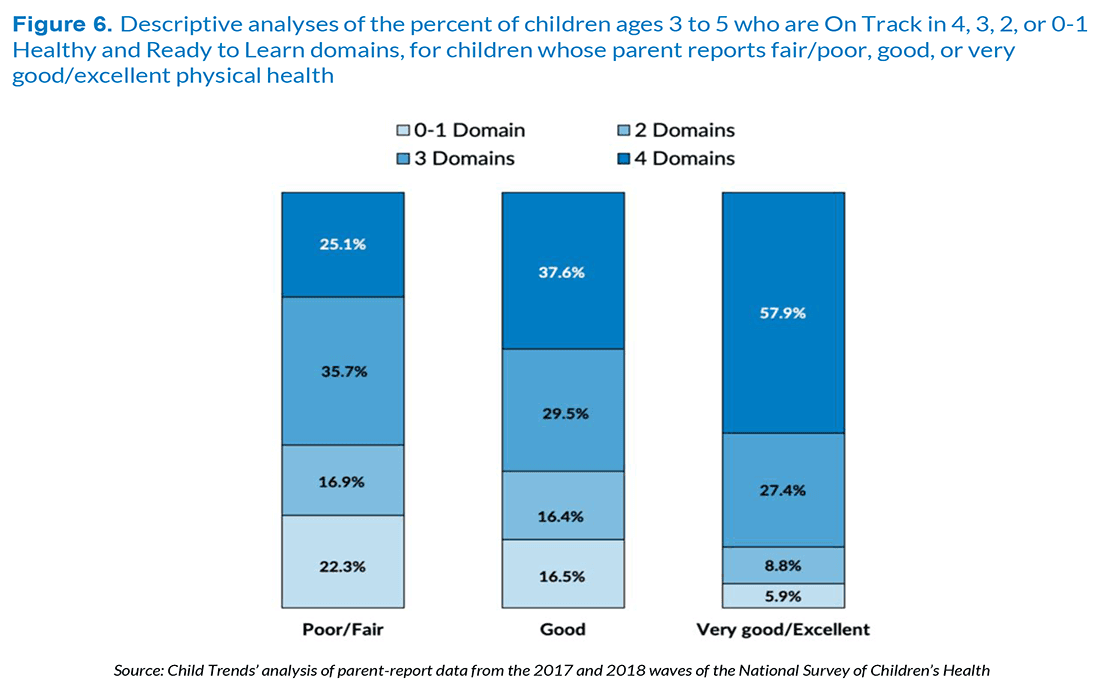

Preschool children are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn when their parents are physically healthy.

Parental health is associated with parental reports of children’s health, such that parents who report poor health for themselves also tend to report poor health for their children.[10] The NSCH asked all parent or caregiver respondents to report on their own physical health and whether it is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. For this analysis, these responses were collapsed into three categories, as shown in Figure 6.

As noted for mental and emotional health, there is a strong positive association between parent’s physical health and their preschool child’s health and readiness to learn. Specifically, the percent of preschool children who are On Track in all four HRTL domains increases from 25 percent to 38 percent to 58 percent as parent’s reported physical health improves, correspondingly, from fair/poor to good to very good/excellent. Similarly, as a parent’s reported level of health improves, the proportion of preschool children On Track in zero or one domain declines, from 22 percent to 17 percent to 6 percent. When we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure, excellent/very good parental health continues to be associated with the child’s HRTL score; however, good parental health is no longer associated statistically significantly with the child’s HRTL score.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that the parent’s physical health is related to whether the child is On Track in all four of the individual HRTL domains (see Appendix C), not simply the overall measure of HRTL.

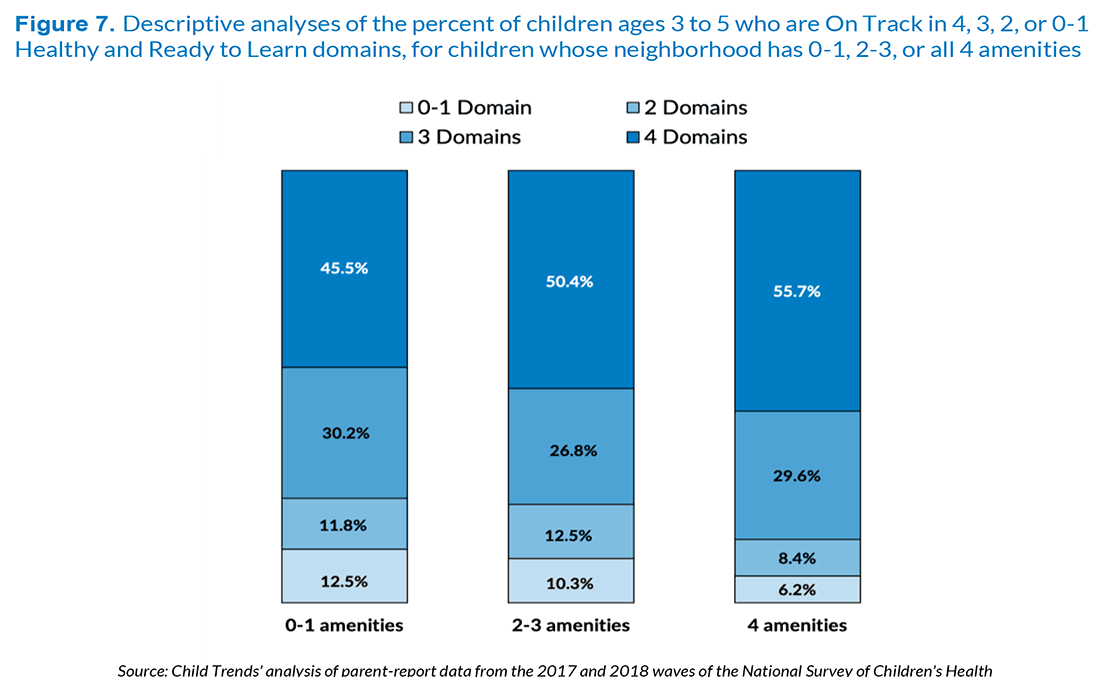

Preschoolers’ health and readiness to learn is moderately related to the number of amenities in the family’s neighborhood.

Neighborhood conditions and amenities have also been found to be associated with young children’s development and school readiness.[11] Neighborhood amenities are measured by four items in the NSCH that ask parents whether their neighborhood has parks, sidewalks, a recreation center, and a library. For this analysis, the number of these amenities available in the neighborhood is summed to create an index from zero to four.

While children whose neighborhoods enjoy more amenities are more likely to be On Track for health and readiness than children whose neighborhoods have fewer amenities, the magnitude of the differences is less striking than for measures of family functioning. That is, the proportion of children On Track in all four domains rises from 46 percent when neighborhoods have zero or one of these amenities, to 50 percent when neighborhoods have two or three amenities, and to 56 percent when neighborhoods have all four amenities. Similarly, the proportion of children who are only On Track in zero or one domain or in two domains is higher when the number of amenities is lower. The differences depicted in Figure 7 are not small, but the magnitude of the differences is smaller than those found for family and parenting characteristics in Figures 1 through 6. When we controlled for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure, having two to three amenities remained statistically significant; however, surprisingly, having all 4 amenities was not significantly associated with being more healthy and ready to learn.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that the presence of neighborhood amenities is associated with being On Track in three of the individual HRTL domains, the exception being social-emotional development (see Appendix C).

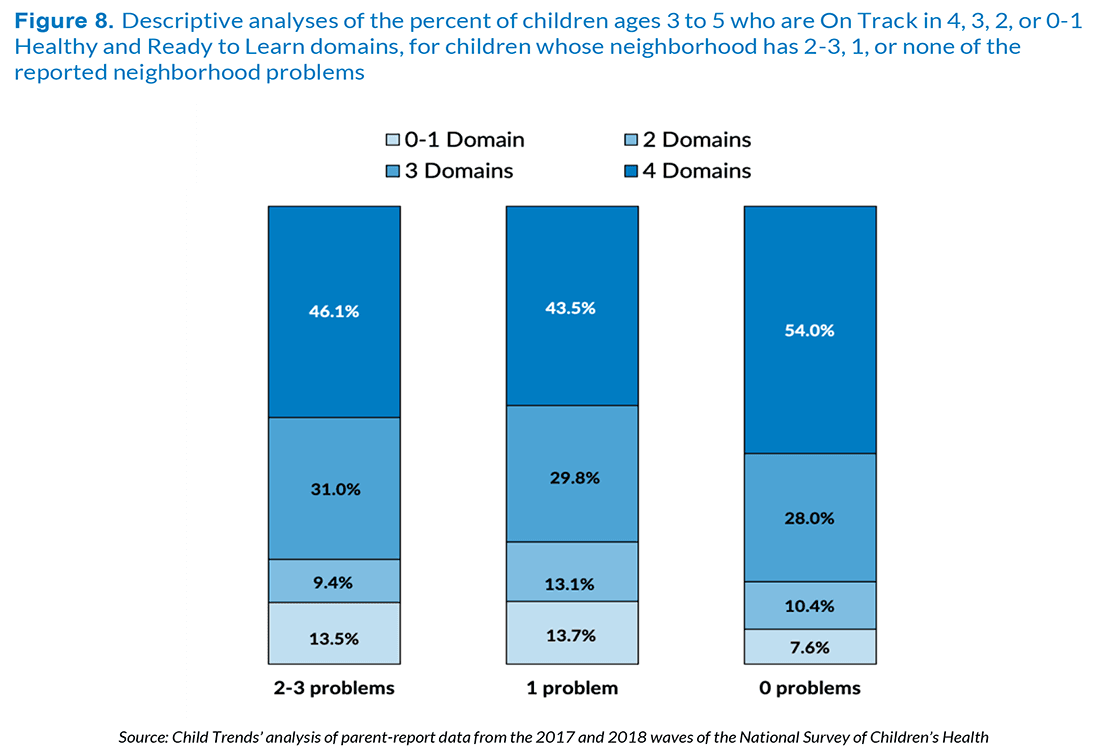

When families live in a neighborhood with problems, their preschool children are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn, compared to preschoolers whose neighborhoods do not have these problems.

Research indicates a link between neighborhood problems or safety and school readiness, such that a greater proportion of children living in neighborhoods with few problems are ready for school compared with those in neighborhoods with problems or unsafe conditions.[12],[13] In the current analyses, neighborhood problems were measured by three items: litter or garbage on the street or sidewalk, poorly kept or rundown housing, and vandalism such as broken windows or graffiti. These three items are summed to provide an index of neighborhood problems.

Figure 8 shows that children living in neighborhoods with any of the specified neighborhood problems were less likely to be described as healthy and ready to learn. Specifically, 46 percent and 44 percent of children were On Track for health and readiness in all four domains when there were two to three problems or one problem, respectively, compared to 54 percent when none of these neighborhood problems were reported. Differences in health and readiness in three versus two domains are relatively modest with respect to the number of reported neighborhood problems; however, children in neighborhoods with none of the specified neighborhood problems are about half as likely to be On Track only in zero or one domain. In analyses that controlled for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure, living in a neighborhood with two to three problems remained associated with being less healthy and ready to learn.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that neighborhood problems are associated with children being On Track in the self-regulation and health domains, but not in the early learning or social-emotional domains (see Appendix C).

Preschool children whose parents feel that their neighborhood is supportive of families and children are considerably more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than their peers whose parents do not report neighborhood support.

Neighborhood cohesion and stability are important influences on family mental health and children’s school readiness.[14],[15] Given this, we further examined neighborhood supportiveness. Neighborhood support was measured with four items in the NSCH, in which parents reported whether they definitely or somewhat agree or disagree that: people in their neighborhood help each other out; people watch out for each other’s children; their child is safe in their neighborhood; and they know where to go for help when they encounter difficulties. Responses were added and categories were coded as low, medium, and high (see Appendix B for items and coding).

Preschool children whose parents report living in neighborhoods that the parent describes as supportive are considerably more likely to be On Track for health and readiness in all four domains, as shown in Figure 9. That is, 63 percent of the children whose neighborhoods are reported to be highly supportive are On Track in all four domains, while 43 percent and 45 percent of children from neighborhoods reported to be low or medium, respectively, in their supportiveness are On Track for health and readiness in all four domains. Similarly, if their parents report living in a neighborhood with low or medium supportiveness, 13 percent are healthy and ready to learn in only zero or one domain, compared with 5 percent for children whose parents report living in a highly supportive neighborhood. In analyses that controlled for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure, living in a highly supportive neighborhood continued to be significantly and positively associated with being healthy and ready to learn.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that neighborhood supportiveness is associated with the proportion of children who are On Track in each of the four of the individual HRTL domains (see Appendix C), not just the overall measure of HRTL.

Discussion

The family and neighborhood measures included in the National Survey of Children’s Health were chosen because a large body of research has found that they affect children’s health and development. This brief considers whether these family and neighborhood factors, as reported by parents, are associated with the health and school readiness of children ages 3 to 5 as assessed in the Healthy and Ready to Learn measure.

Throughout this brief, we have shared descriptive information, along with analyses that control for confounding differences in the overall proportion of children who are On Track in all four domains. We have noted that most of the differences discussed in this brief continue to be statistically significant when we control for social, demographic, and economic factors – specifically, family poverty, parent education, child sex, family structure, and race/ethnicity. When we account for these factors, we may or may not continue to see evidence of a relationship between school readiness and a given family measure. For example, the association of being HRTL with family strength continues to be statistically significant. However, the relationship between being HRTL and emotional support becomes non-significant. That suggests that parents who are unable to access emotional support may differ in terms of their education or income. For the analyses presented in this brief, all of the relationships between being HRTL and the family and neighborhood variables remain significant, except for emotional support; with controls, the difference between parents with and without emotional support falls short of being statistically significant.

To receive the latest updates on the Kindergarten Readiness National Outcome Measure, sign up for our newsletter.

Analyses reported in this brief find that children from more supportive families and neighborhoods are more likely to be On Track for being Healthy and Ready to Learn in all four domains using the parent-report measures embedded within the NSCH. For example, the importance of parent mental health, including parent depression, for children’s development, has been documented in many studies.[16] In these analyses we also find that the parent’s assessment of their mental and emotional health is strongly correlated with whether their preschool child is On Track for being healthy and ready to learn. Similarly, routines such as a regular bedtime and family meals have previously been found to be important to children’s development,[17] and here we find them to be clearly associated with children’s health and readiness to learn.

A clear implication of these analyses is that the well-being of the parent is associated with the extent to which their child is healthy and ready to learn. In particular, the parent’s reported physical health and their mental/emotional health are both strongly associated with whether their preschool child is On Track on the overall HRTL measure and with being On Track in the four individual domains.

Also, research studies have found that parents benefit from having supportive relationships.[18] The indicators that assess whether parents have emotional support and whether the neighborhood is supportive for children and families are both associated with the child’s health and readiness to learn (although, as noted above, the measure of emotional support becomes non-significant in analyses that control for confounding factors). Moreover, the magnitude of the differences found with the indicators of neighborhood amenities and problems, while important, are somewhat smaller than the magnitude of the differences found for the measure of neighborhood supportiveness for parenting. Also, while the indicators of neighborhood amenities and problems are both related to children’s overall health and readiness to learn, the association is only found for the self-regulation and health domains.

These patterns align with research findings and theory that family factors are of greater importance for children’s development than neighborhood factors; research indicates that neighborhoods influence children’s development indirectly via effects on parents, such as by affecting maternal mental health, stress, perceived supports, and supportive parenting behaviors. These analyses generally indicate that preschool children’s health and readiness to learn is most clearly associated with measures of their family characteristics, activities, and circumstances—factors that are proximal to preschool children’s daily lives and relationships.[19] The magnitude of the associations for more distal factors, such as neighborhood amenities and problems, tend to be smaller and less consistent across the four developmental domains.

Conclusion

These analyses find that family factors are consistently and strongly associated with the extent to which preschool children are healthy and ready to learn. In addition, neighborhood factors, particularly neighborhood supports for children and families, also tend to be associated with children’s readiness. These findings suggest that, if policymakers want to improve children’s health and readiness to learn, they need to support families and communities.

We recognize that the associations described here are cross-sectional, and we note that the National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn examined here is a pilot measure that is likely to be strengthened in the coming year. In addition, all measures are reported by parents. Nonetheless, we note that the kinds of patterns discussed in this brief have also been found in analyses of the 2016 NSCH, using a Healthy and Ready to Learn measure that is slightly different in terms of the variables and coding of items in the measure. These patterns, therefore, appear to be very consistent.

We also note that most of the associations described in this brief remain statistically significant when we control for family poverty, parent education, child gender, race/ethnicity, and family structure. The most notable exception is the variable measuring whether the parent has someone who can provide them with emotional support; this may reflect the fact that nearly all respondents are able to identify someone. In fact, many are able to identify a range of people who provide support, including professionals, spouses/partners, clergy, and friends; however, we do not know about the quality and consistency of that support.

Previous researchers have pointed out that family, parent, and neighborhood characteristics are associated with children’s pre-academic and social development, and physical health.[20],[21],[22] However, the Healthy and Ready to Learn National Outcome Measure permits an examination of these associations for a national sample of preschool children. Moreover, given the richness of the data in the NSCH, it is possible to identify varied factors that are linked with whether a child is On Track for being healthy and ready to learn in individual developmental domains, as well as On Track across domains. These data will be available for each state and will be made available on an annual basis, as a part of the National Survey of Children’s Health.

Download

References

[1] Details on each covariate including item wording and response options are available in Appendix B.

[2] The demographic, social, and economic variables include parents’ education, family structure, family income, food security, household primary language, access to health insurance, children’s race, children’s gender, and children’s age. The child experiences include include frequency of book reading, amount of screen time and sleep, presence of a special health care need, access to family-centered care in a medical home, and exposure to adverse childhood experiences.

[3] Moore, K. A., Chalk, R., & Scarpa, J. (2002). Family Strengths: Often overlooked, but real. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends.

[4] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Parenting knowledge, attitudes, and practices. In Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21868

[5] Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., & Mathis, E. T. (2014). Parenting programs that promote school readiness. In Promoting school readiness and early learning: Implications of developmental research for practice (pp. 253–278). The Guilford Press.

[6] National Academies of Sciences, E. (2016). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0-8. https://doi.org/10.17226/21868

[7] Pew Research Center. (2015). Parental satisfaction, time and support. In Parenting in America. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/17/2-satisfaction-time-and-support/

[8] Kahn, R. S., Brandt, D., & Whitaker, R. C. (2004). Combined effect of mothers’ and fathers’ mental health symptoms on children’s behavioral and emotional well-being. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.8.721

[9] Pierce, M., Hope, H. F., Kolade, A., Gellatly, J., Osam, C. S., Perchard, R., Kosidou, K., Dalman, C., Morgan, V., Prinzio, P. D., & Abel, K. M. (2019). Effects of parental mental illness on children’s physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.216

[10] Waters, E., Doyle, J., Wolfe, R., Wright, M., Wake, M., & Salmon, L. (2000). Influence of parental gender and self-reported health and illness on parent-reported child health. Pediatrics, 106(6), 1422–1428. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.6.1422

[11] Minh, A., Muhajarine, N., Janus, M., Brownell, M., & Guhn, M. (2017). A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: How, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health & Place, 46, 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.012

[12] DeCarlo Santiago, C., Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008

[13] Lapointe, V. R., Ford, D. L., & Zumbo, B. D. (2007). Examining the relationship between neighborhood environment and school readiness for kindergarten children. Early Education and Development, 18(3), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701610846

[14] DeCarlo Santiago, C., Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008

[15] Lapointe, V. R., Ford, D. L., & Zumbo, B. D. (2007). Examining the relationship between neighborhood environment and school readiness for kindergarten children. Early Education and Development, 18(3), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701610846

[16] Pierce, M., Hope, H. F., Kolade, A., Gellatly, J., Osam, C. S., Perchard, R., Kosidou, K., Dalman, C., Morgan, V., Prinzio, P. D., & Abel, K. M. (2019). Effects of parental mental illness on children’s physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.216

[17] National Academies of Sciences, E. (2016). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0-8. https://doi.org/10.17226/21868

[18] Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 198–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12646

[19] National Academies of Sciences, E. (2019). Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25201

[20] Heckman, J. J. (2008). Role of income and family influence on child outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.031

[21] Minh, A., Muhajarine, N., Janus, M., Brownell, M., & Guhn, M. (2017). A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: How, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health & Place, 46, 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.012

[22] National Academies of Sciences, E. (2016). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0-8. https://doi.org/10.17226/21868

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram