The rate of child poverty in the United States has more than doubled, from 5.2 percent in 2021 to 12.4 percent in 2022, according to newly released data from the Census Bureau, translating to 5.2 million more children living in poverty than in 2021. This increase follows the expiration of most of the COVID-era programs that resulted in unprecedented reductions in child poverty. The new Census data highlight the critical role of pandemic-era social safety net expansions in the dramatic decrease in child poverty rates in 2020 and 2021. Despite high rates of unemployment during the pandemic, child poverty (as measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure) declined by 25 percent in 2020 and by nearly 50 percent in 2021, largely thanks to stimulus payments and temporary expansions to government programs such as the Child Tax Credit, Unemployment Insurance, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), among others. The expiration of these programs reverses the progress of the last two years.

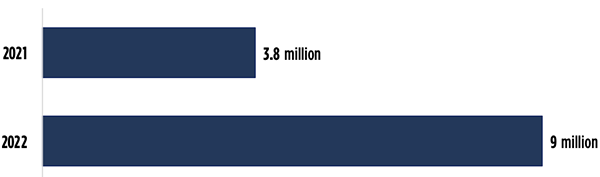

Number of children in the United States experiencing poverty in 2021 and 2022

Source: U.S. Census Bureau’s Poverty in the United States: 2022.

What should we make of this substantial increase in the rate of children experiencing poverty?

It seems a truism, but it’s worth stating: When we end supports that have been shown to dramatically cut child poverty, we will see the rates of child poverty revert back to their previous levels. So, it is perhaps not unexpected to see 2022 child poverty rates return to pre-pandemic levels.

Child poverty rates, as measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure, 1967-2022

Sources: Poverty rates from 1967-2020 are Historical Supplemental Poverty Measure data from the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy; Poverty rates from 2021-2022 are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Poverty in the United States: 2022. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Note: Changes in how CPS ASEC data have been collected and processed mean that child poverty estimates beginning in 2014 and 2018 may not be directly comparable to previous years.

Yes, it’s true that the temporary measures meant to boost family income during the pandemic did what they were supposed to do at a time of economic crisis. And thanks to a return to low rates of unemployment, the rate of child poverty in 2022 remains low from a pre-pandemic historical perspective. However, approximately 9 million children live in families experiencing poverty even though they don’t need to: We already know what works to lift them out of poverty.

What should we do now?

Implement permanent, proven solutions to protect children from the hardships of living in poverty. The payoff is huge for the health and well-being of our nation’s children and for our society as a whole: For every $1 we invest in our children, our society reaps $8 worth of rewards, according to a recent study. To prevent further loss of the progress we made in reducing child poverty over the past quarter century, the United States needs permanent policies that build on the lessons learned through the pandemic:

1. Make it simple for families to access the benefits to which they are entitled.

Billions of dollars in benefits—yes, billions (spelled with a b!)—are left unclaimed each year because our systems have made them difficult for families to access and use. In the process of disbursing stimulus payments and implementing the expanded Child Tax Credit, we learned how to make benefits more accessible to families. But as the expanded CTC expired, important policy lessons learned about making benefits easier to access were left on the table, including the following:

- Reaching families through systems they already interact with (e.g., the tax system) to effectively assess eligibility and disburse benefits

- Providing multiple access points to reach families not already connected to existing systems (e.g., creating a nonfiler portal so that families who don’t need to file taxes can still access the credit)

- Distributing payments monthly so families can receive support when they need it—and offering multiple options for disbursement (e.g., direct deposit, check, and preloaded debit card options)

2. Ensure that all children who need support are able to access it.

By the latest estimations, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), Black, and Hispanic families are more likely to experience poverty than their peers. In 2022, AIAN, Black, and Hispanic children were more than 2.5 times as likely to experience poverty as their White peers. Many of these children and their families are excluded from our country’s social safety net either through formal eligibility exclusions or through requirements or administrative burdens disproportionately experienced by families of color. But temporary pandemic-era policies showed us that we could not only significantly reduce levels of child poverty, but also reduce racial and ethnic disparities in economic well-being by removing restrictions that disproportionately exclude certain populations from social safety net programs. For example:

- The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program expanded unemployment benefits to independent contractors and gig workers, groups that are disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

- The expanded Child Tax Credit based eligibility on children’s citizenship status rather than that of their parents (as with the current CTC).

3. Support families’ abilities to work to provide for their families.

Work is an incredibly effective way to support a family—when a job can be found and maintained. Less than 4 percent of individuals who worked full-time, year-round were in poverty in 2022. But the pandemic made clear that workers must have the resources they need to balance work with family responsibilities. Access to affordable, dependable, high-quality child care and paid family and medical leave is critical for sustained employment—particularly for single parents. The American Rescue Plan provided critical support during the pandemic that allowed child care providers to keep their doors open and their parents to work. As we face the expiration of these funds, we need a permanent investment in child care that ensures that all families have access to affordable care and that child care workers are paid wages that allow them to support their own families.

4. Ensure that benefit levels are sufficient to meet eligible families’ needs during times of economic hardship.

The generosity of our social supports is directly related to the number of children these supports are able to lift out of poverty. In order to meet eligible families’ needs during times of national economic hardship, benefit levels must be closely pegged to inflation to keep up with higher costs of living. Coordination across safety net programs and combined application processes can not only improve administrative efficiency but also maximize the short- and long-term benefits for children and their families.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the following individuals for their support on this piece: Brent Franklin, Jody Franklin, Lina Guzman, Kristen Harper, Emily Theresa Maxfield, Olga Morales, Catherine Nichols, Astha Patel, and Stephen Russ.

Suggested citation

Thomson, D., & Ryberg, R. (2023). 5 million more children experienced poverty in 2022 than in 2021, following expiration of COVID-era economic relief. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/9226y4878j

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram