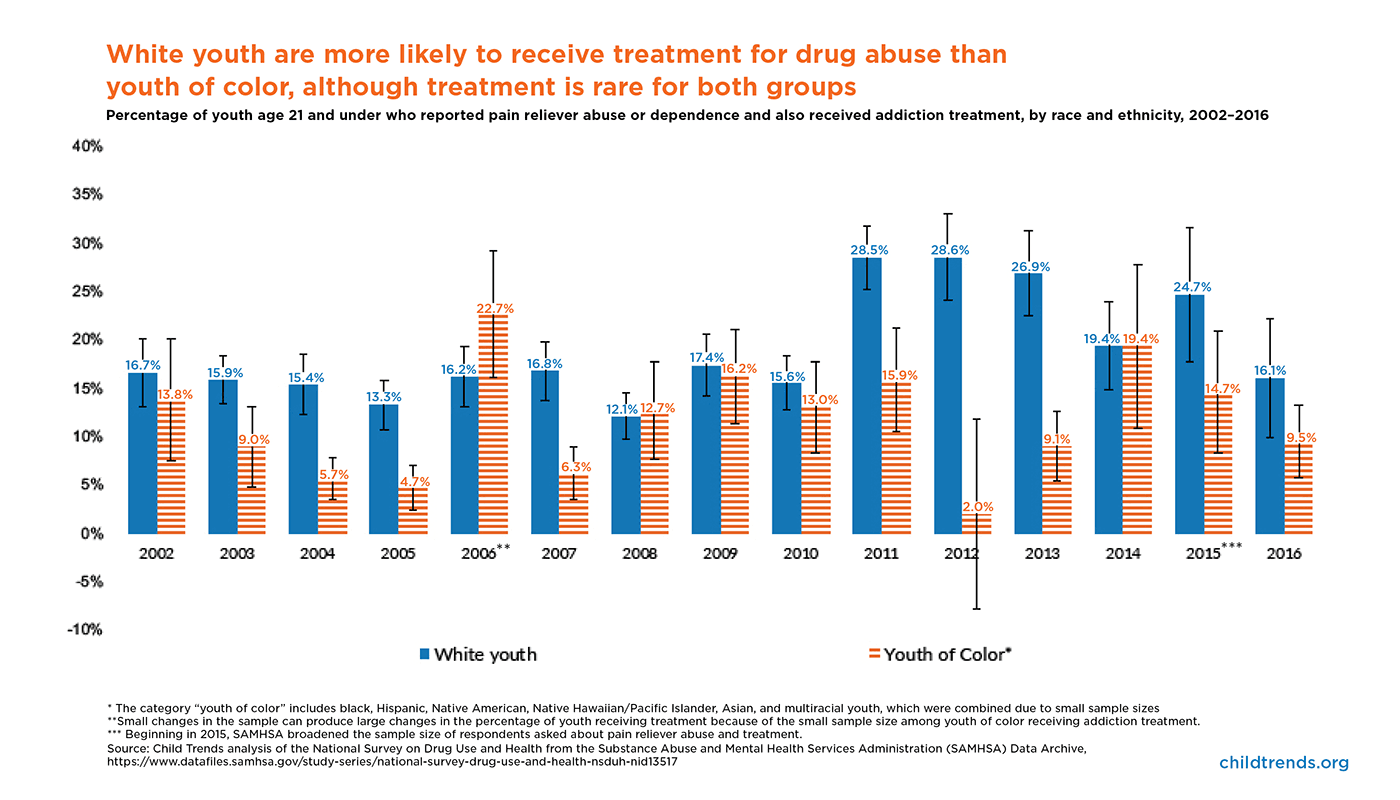

CORRECTION (3/22/2019): Several numbers in this blog have been updated to correct inaccurate weighting of the variance estimates. The corrected numbers below show very small changes in the percentages of youth who received treatment. The findings about the persistent gap between white youth and youth of color who receive drug addiction treatment remain unchanged.

Only a small percentage of youth who report pain reliever (including opioid) abuse or dependence receive addiction treatment, and youth of color are significantly less likely to receive treatment than their white peers. According to Child Trends’ analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, this gap between white youth and youth of color age 21 and under has persisted almost every year since 2002, when opioid prescription deaths began to rise. As of 2016, 16.1 percent of white youth who abused pain relievers received treatment, compared to 16.7 percent in 2002. Just 9.5 percent of youth of color who abused pain relievers received treatment in 2016—a 4.3 percentage point drop from 2002 (when 13.8 percent received treatment) and persistently lower than their white counterparts.

In the Child Trends analysis, youth of color includes black, Hispanic, Native American, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, and multiracial youth; these groups were combined due to small sample sizes, which is regrettable since each group’s experiences in attempting to access treatment are different.

During the period from 2002 to 2016, some positive steps were taken; overall, though, these do not seem to be associated with either increases in the percentage of youth receiving addiction treatment or with closing the gap between white youth and youth of color. These positive steps include increased government spending on substance abuse during the Great Recession, largely through Medicaid. It’s possible that this increase temporarily closed the gap between white youth and youth of color because most government spending was on Medicaid and nearly 60 percent of nonelderly Medicaid enrollees were people of color in 2008. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in 2010, also increased insurance coverage among youth, but research has found that the ACA did not increase substance abuse treatment among young people.

To increase the percentage of all youth who receive treatment for drug abuse and begin to close this gap between white youth and youth of color, decision makers must increase access to addiction treatment for youth. Youth can receive addiction treatment from specialized facilities, or (potentially) from their pediatrician or primary care doctor. Unfortunately, the number of substance abuse treatment facilities did not change from 2007 to 2017, and fewer than one third of facilities offer programming for youth. Additionally, only 10 percent of facilities offer medication-assisted therapy, which is considered best practice for treating opioid addiction. While physicians have been able to access waivers to provide medication-assisted treatment through their existing practice since 2000, fewer than 1 percent of pediatricians are waivered to provide treatment and 43 percent of counties in the United States have no waivered providers.

Critically, even if treatment becomes more available, youth of color may be less likely to seek treatment than their white peers. Youth of color are less likely to be insured, screened for substance abuse, and referred to treatment by clinical providers. In addition, some barriers to substance abuse treatment are specific to particular racial and ethnic groups. For example, efforts to expand substance abuse treatment can differ for Native American youth, who may access health care through the Indian Health Service, tribal programs, and in rural areas. In the black community, substance abuse has historically been addressed through the criminal justice system, rather than via treatment provision, which could discourage black youth from seeking treatment. Treatment programs must be culturally tailored to the communities they serve and cognizant of these kinds of fraught histories.

Click here to view a version of the chart displaying the standard errors. While the standard error bars overlap in some years, the gap is persistent and the error bars do not overlap in approximately half of the years measured. Additionally, this gap is present in other data sets. The wide standard errors are the result of a small sample size and is indicative of the need for increased drug addiction treatment for youth.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram