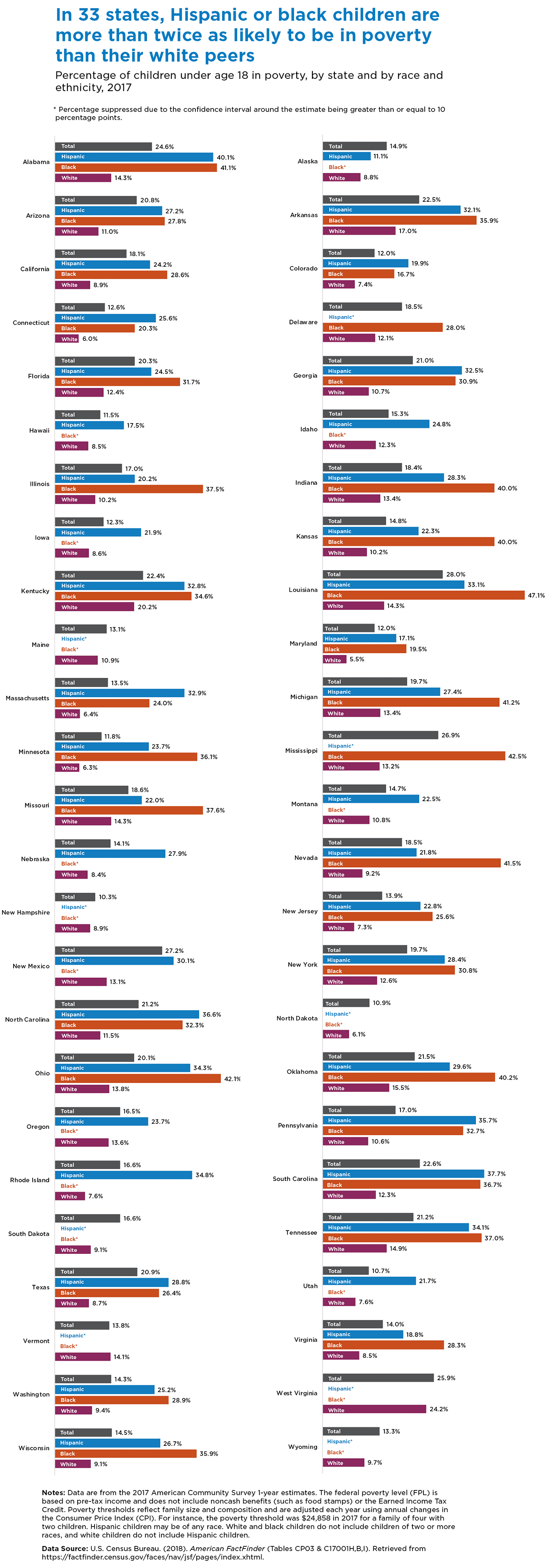

In 32 states, the percentage of black children in poverty was at least twice as high as among non-Hispanic white children, according to 2017 data recently released from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. This represents all but one of the 33 states for which there were reliable estimates of the population of black children. In 18 states, the rate among black children was at least three times as high as among their white peers. In Nevada, the poverty rate among black children was more than four times as high, and in Minnesota it was more than five times as high.

Hispanic children were also at least twice as likely to live in poverty as their non-Hispanic white counterparts in 33 states. This number represents over three-quarters of the 41 states for which there were reliable estimates for Hispanic children. In 12 states, the poverty rate among Hispanic children was at least three times as high as among non-Hispanic white children. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, the poverty rate among Hispanic children was more than four times as high, and in Massachusetts it was more than five times as high.

Other notable state-level findings in 2017:

- New Hampshire had the lowest proportion of children in poverty (10.3 percent), while Louisiana had the highest (28 percent).

- Among non-Hispanic white children, the poverty rate was lowest in Maryland (5.5 percent) and highest in West Virginia (24.2 percent).

- Among black children, the poverty rate was lowest in Colorado (16.7 percent) and highest in Louisiana (47.1 percent), excluding those states with unreliable estimates.

- The poverty rate among Hispanic children was lowest in Alaska (11.1 percent) and highest in Alabama (40.1 percent), again excluding states with unreliable estimates.

Click here to download the data (XLS).

Numerous social, historical, and policy factors have contributed to these racial/ethnic poverty gaps. Racial discrimination in such areas as home loans and hiring practices, and a history of school segregation, have exacerbated these disparities over time. The legacies of racism also account, in part, for the fact that black and Hispanic adults continue to have higher rates of unemployment and single-parenthood, and lower rates of college completion and homeownership, than their white counterparts, resulting in reduced income and wealth.

Being raised in poverty puts children at risk for a wide range of problems, including impaired cognitive, social, and emotional functioning, as well as poorer health. Child poverty is also associated with negative outcomes in adulthood, such as lower academic achievement, lower employment rates, poorer health, and deficits in working memory.

A number of strategies have shown promise in reducing child poverty. Most include bolstering family income directly through tax credits, higher wages, savings accounts, or conditional cash transfers; or supplementing income through programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Other strategies include helping parents gain the skills essential for higher-wage jobs.

The Child Trends DataBank has information on national trends in child poverty, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS COUNT Data Center provides a breakdown of state trends.

This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram