Getting a good job early in one’s work life can help set young adults on an upward path of economic mobility. A good job is one that pays well, provides good benefits, and (where feasible) allows for a flexible schedule. A good job can also provide opportunities to develop skills, advance in one’s career, and improve one’s physical and mental health through access to benefits and better pay. To understand the life course implications of holding a good job early in life, we simulated the long-term effects of having a higher-paying job at age 24 that provides benefits such as health insurance, retirement plans, and paid time off. We found that having a better job early in life improves lifetime earnings substantially for all racial groups; however, these improvements aren’t sufficient to close the earnings gap between White people and Hispanic or Black people (estimated to be as high as $350,000 in average discounted lifetime earnings).[1]

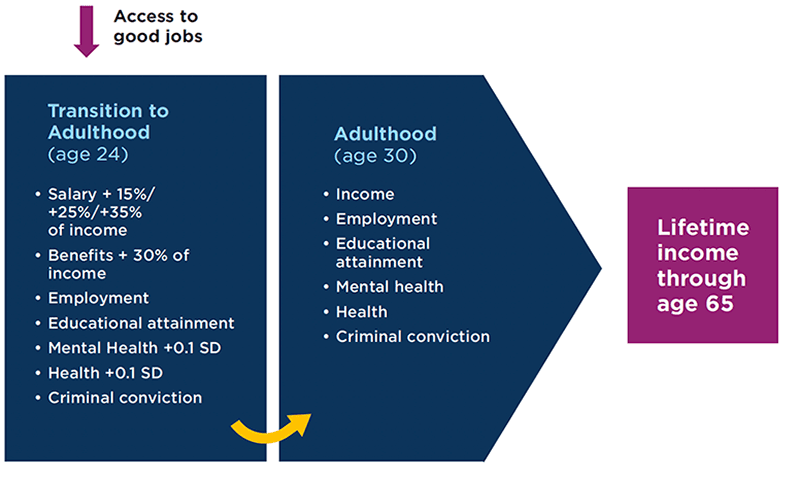

We simulated a good job by changing three measures of job quality: First, for those who do not have a bachelor’s degree and who earn no more than $30,000 a year, we increased annual earnings at age 24 by 35 percent for those making $1 to $12,000; by 25 percent for those making $12,001 to $24,000; and by 15 percent for those making $24,001 to $30,000. (The rationale for this stairstep approach is that low-education and very low-wage workers need large earnings increases to approximate a substantial improvement in their jobs.) Second, we also increased earnings by an additional 30 percent to approximate the effects of the average employer-provided fringe benefits, such as health insurance, retirement plans, and paid time off. Third, we also added a conservative 0.1 standard-deviation change in both the mental and physical health scales in the transition to adulthood, given that work benefits have positive effects on workers’ physical and mental health.

Figure 1: Progressive Effects of the Good Jobs Simulation Throughout the Adult Life Course

After applying our simulations, we found that having a better job at age 24 translates to better pay at age 30: On average, there was an increase of about $4,800 in annual earnings at age 30 (2018 dollars) for young adults who access these jobs. The simulation also showed an average increase in discounted lifetime earnings of about $52,000; this is equivalent to about $100,000 in undiscounted earnings throughout the young adults’ lives across all racial groups. As a result of structural/racial discrimination in the workforce, these improvements are more likely to affect Black and Hispanic people, who are more likely to work in occupations with lower wages.

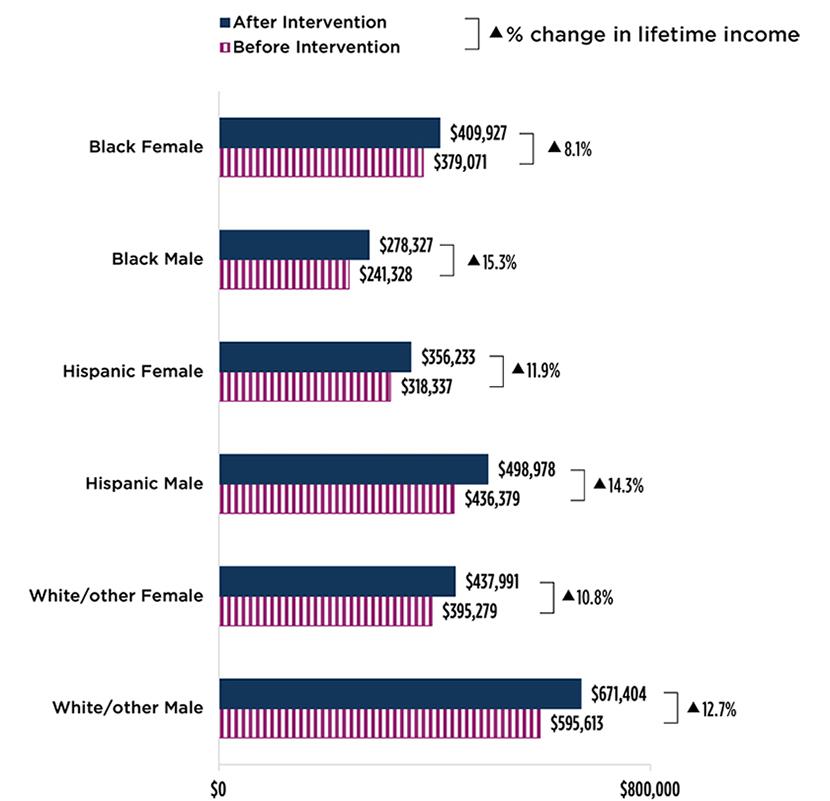

However, the changes modeled in our simulation weren’t sufficient to close the earnings or well-being gaps between White people and Black and Hispanic people. The largest earnings increases in absolute terms were for Hispanic and White men; while Black women and men saw 8 percent and 15 percent earnings increases, respectively, both groups remained among the lowest-earning groups examined after the simulation (Figure 2). And while young adults’ mental and physical health at age 30 improved slightly after the simulation (0.03 to 0.06 standard deviation increases), the largest increase was found for White women.

Figure 2: All Simulated Demographic Groups Saw Increases in Lifetime Earnings, but Racial and Ethnic Gaps Remained

Change in lifetime earnings in our job quality simulation among young adults who earn no more than $30,000 and do not have a bachelor’s degree, by race or ethnicity and sex

While our simulations show long-term benefits for young adults who enjoy good jobs, many jobs in the United States do not currently provide good pay and/or good benefits. This makes it harder for low-income workers to achieve economic mobility and a better quality of life, a situation that seems to have gotten worse in recent years. Fortunately, several policies and programs can promote improvements in access to or availability of good jobs for young people. Work-based learning, job shadowing, and apprenticeships can link young adults to employers and contacts whom they might not otherwise meet, thereby giving them a pathway to accessing better jobs. Other alternatives include requiring employers to provide benefits via legislation, private sector initiatives that expand access to nonmonetary benefits, efforts to strengthen workplace practices and worker protections through regulation, and encouraging employees to participate in workplace decisions on job practices via expanded worker engagement. If employers do not act now, they may risk workers looking to leave their current jobs for another position with higher wages and better benefits.

Child Trends and its partners at the Urban Institute recently released a report, Understanding and Quantifying Crossroads Moments, in which we use the Social Genome Model (see more about the model below) to examine how key moments at which people embark on a particular path—moments we refer to as “crossroads”—influence later outcomes.

Learn more about the Social Genome Model, a partnership between Child Trends, the Brookings Institution, and the Urban Institute.

Footnote

[1] Lifetime earnings are discounted present values in 2018 dollars. Earnings are discounted since the value of present earnings is higher than the value of future earnings due to potential investments (i.e., money invested today receives a higher payoff than money invested later).

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram